Are geopolitical shifts contributing to a more diverse foreign enrolment?

- As always, the shape of international student mobility is affected by geopolitical trends

- China’s power and influence in Asia as well as parts of Africa has grown rapidly in the span of just a few years

- Western universities are having to quickly expand the number of regions and countries they recruit in as a result

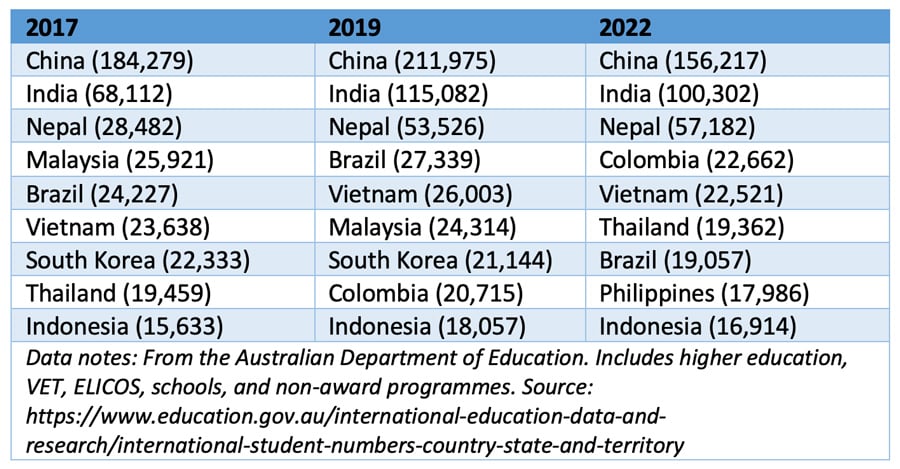

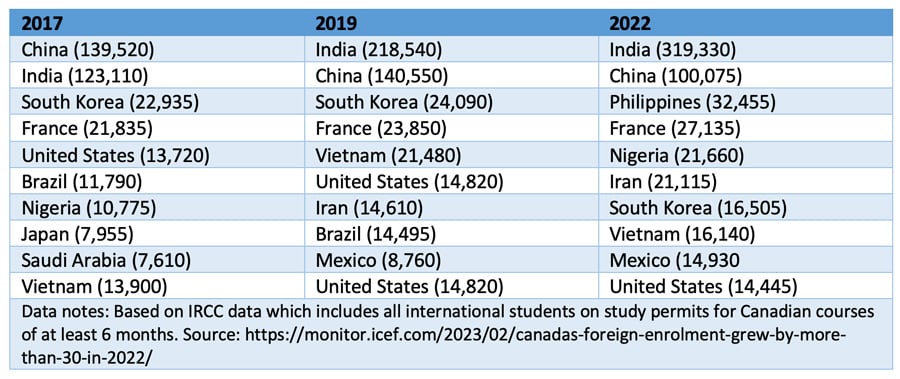

- Changes in the top 10 sending markets for Australia and Canada in 2017, 2019, and 2022 underline this trend

Global geopolitics have shifted dramatically over the past decade, but the shifts have never been so apparent as over the past 13 months. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has quickly united the West; cemented ties between Russia, China, and Iran; and convinced several other governments – notably India’s – that a careful neutrality is the wisest move at this point.

China’s power is clearly visible in its strategic alignment with Russia and is a major force shaping a new international order. China's ascent is also affecting (1) where Western educators are recruiting and (2) where international students are choosing to study.

China is a centre of research and innovation

The Chinese outbound student market has for years been flattening and even shrinking for the US, Canada, and Australia. Chinese enrolments have declined by -20%, -28%, and -15%, respectively, in those three countries since 2017. Part of the reason is somewhat ironic: China sent so many students out in the past decade that is no longer needs to do so now.

Specifically, hundreds of thousands of Chinese students have graduated in the past decade from top-ranked Western institutions and many of them have returned home. Those graduates are fuelling the Chinese economy and education system, and China is now leading the US in 37 of 44 technology fields analysed in a year-long study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. In the study report, the authors note:

“For some technologies, all of the world’s top 10 leading research institutions are based in China and are collectively generating nine times more high-impact research papers than the second-ranked country (most often the US). We also see China’s efforts being bolstered through talent and knowledge import: one-fifth of its high-impact papers are being authored by researchers with postgraduate training in a Five-Eyes country.”

(The Five-Eyes is an intelligence-sharing alliance of five countries: the US, Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand.)

As China’s political and economic influence expands, so too has its higher education system, both in terms of quality and capacity. Several Chinese institutions now have a place in the top tiers of international rankings.

Such developments illustrate why – pandemic restrictions aside – so many Chinese and Asian high-school-aged students now feel they have at least as much reason to study in China as in the West.

China’s new stature a factor driving diversification

It is no coincidence, given China’s growing power, that many Western schools and universities are casting a far wider net in their recruitment efforts. India remains a focus, as do other South and Southeast Asian markets, but South and Latin America as well as Africa are increasingly important.

We’ve created two tables to illustrate just how much the international student populations of Canada and Australia have changed over just a few years. Of course, not everything can be tied to new geopolitical alignments, but slowing Chinese outbound is at the heart of much of the dynamism you’ll see in the charts.

Australia

An important note: Australia’s borders were closed as a pandemic response for much longer than Canada’s, and 2022 data thus represents an earlier point in Australia’s international education sector recovery than Canada’s. New data coming out of Australia regarding commencements suggest that enrolments should climb significantly for Australia in 2023.

That said, some of the most notable changes in Australian sending markets are:

- Philippines (+4% since 2019 but +112% since 2017): 17,976 students in 2022

- Colombia (+9.4% since 2019 but +61% since 2017): 22,662 students in 2022

- India (-13% since 2019 but +47% since 2017): 100,302 students in 2022

- Pakistan (+5% since 2019 and +24% since 2017): 15,875 students in 2022

- Malaysia (-37% since 2019 and -40% since 2017): 15,420 students in 2022

- South Korea (-39% since 2019 and -42% since 2017): 12,911 students in 2022

- China (-26% since 2019 and -15% since 2017): 156,217 students in 2022

Canada

An important note: Canada’s post-pandemic recovery has been well underway for some time: the country recorded record-breaking foreign enrolment growth of 30% in 2022 (for a total of 808,000 international students). Foreign enrolment in Canada is now 27% higher than before the onset of the pandemic, and some of the huge increases in some sending markets below are part of that story (the Philippines increase in particular is astounding). Those increases offset significant declines from the key Asian markets of China, Vietnam, and South Korea.

- India (+46% since 2019 and +159% since 2017): 319,130 students in 2022

- Philippines (+320% since 2019 and 724% since 2017): 32,355 students in 2022

- Nigeria (+82% since 2019 and 101% since 2017): 21,660 students in 2022

- Iran (+45% since 2019 and 189% since 2017): 21,115 students in 2022

- Colombia: (+123% since 2019 and +336% since 2017): 12,440 students in 2022

- Mexico (+72% since 2019 and +116% since 2017): 14,930 students in 2022

- Bangladesh (+47% since 2019 and +190% since 2017): 12,295 students in 2022

- China (-29% since 2019 and -28% since 2017 ): 100,075 students in 2022

- Vietnam (-25% since 2019 but +16% since 2017): 16,140 students in 2022

- South Korea (-31% since 2019 and -28% since 2017): 16,505 students in 2022

More turbulence ahead

The geopolitical upheaval linked to the war in Ukraine underlines that no student market can be viewed as entirely stable any more. There is sadly no end in sight yet for the war’s resolution – and no clear sense yet of what the world order will look like in the coming months, or years.

In the meantime, prospective students around the world are receiving more offers and enticements than ever from institutions in a growing number of destinations. The intense competition for students reflects not only institutions’ need to fill places in classrooms in 2023/24, but also governments’ pressing need to strengthen their labour force and research centres and to forge ties with emerging economies.

For additional background, please see: