Why have Chinese student numbers been slower to recover this year?

- Chinese outbound numbers have been relatively slow to rebound so far this year

- There are a number of reasons for this, including some students’ fear of contracting COVID abroad and not being able to return home as a result

- China is still the top sending market for Australia, the UK, and the US and the second-largest for Canada after India

As predicted, the flow of Chinese students to universities in Australia, Canada, the UK, and US has been weakening throughout the first years of the 2020s. There are several reasons for this softening of demand, including:

- Increased capacity and quality in China’s higher education system;

- Chinese employers’ greater interest in hiring Chinese-educated graduates;

- Continuing fears about contracting COVID-19 abroad and being unable to return home;

- Awareness of xenophobia directed towards Chinese students in the US at the outset of the pandemic, when some unfairly associated Chinese students with the emergence of the virus;

- Shifts in global power and influence between China and the West.

The authors of a report published earlier this year by international consultancy Oliver Wyman explain,

“The world is heading in the direction of a new order, diverting from the path of globalisation that had previously been the norm for many years. China, in particular, has been more determined than ever to take measures to build up its national competitiveness in various aspects … Providing quality education is one of the priorities.”

It’s important to note, however, that China continues to send hundreds of thousands of students abroad. Chinese students are still the most represented international student nationality in the US, UK, and Australia and the second most populous group in Canada.

What are the recent trends in Chinese enrolments?

The four major English-speaking destinations are definitely feeling the urgency of diversifying their student source markets as a result of a smaller Chinese outbound trend. For example:

- The UK saw 5% fewer Chinese commencements in 2020/21;

- In that same year, Chinese enrolments in the US declined by 15%;

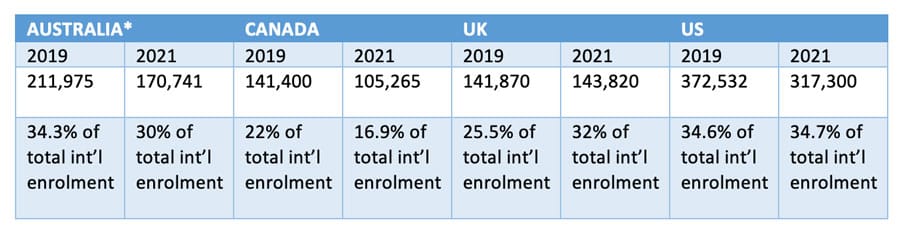

- From 2019 to 2021, the proportion of Chinese students in Canada’s international student population fell from 22% to 17%;

- The proportion of visas given to Chinese students for programmes in Australia in 2021 was 30% of the total, down from 35% in 2019.

If we compare Chinese enrolments in 2019 and 2021, here’s what happened (as you can see, the UK is the only destination bucking the downward enrolment trend, but again, Chinese commencements declined in the UK in 2020/21).

* Australia only opened its borders in December 2021 therefore the recovery pattern of the international education sector is still unfolding. However, given that year-to-date Australian government data shows a 16% decrease in Chinese numbers in April 2022 compared with April 2021, we can assume that Chinese enrolments are continuing to decline. The data does show a notable increase from Nepal, and smaller increases from the Philippines, Thailand, India, and Pakistan.

What’s to be done?

Obviously, educators have more reason than ever to pour energy and investments into diversifying their source countries. At the same time, they do not want to (and could not) abandon the Chinese market, which continues to send a massive volume of students to all four destination countries.

Beyond enrolments, there is a larger imperative: international student mobility is a crucial linchpin of diplomacy and cooperation between nations. When Chinese students study abroad, they enrich their host countries with their perspectives, and when they return home, they carry with them rich experiences, friendships, and networks.

Kim Eklund, Navitas’ regional sales director for greater China, underlines that key to encouraging Chinese enrolments is to understand that Chinese families are making decisions about study abroad in a different way than before the pandemic:

“There is a genuine fear across China, not just of contracting COVID-19 per se, but of strict measures applied to anyone infected or being a close or secondary contact. While they appear unrelated, it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume a link between the concern over COVID-19 and the importance currently placed on factors relating to ranking and quality.

In order to face the risks of travelling and potentially not being able to return home for an extended period of time, a student and their family would want a higher than normal return in terms of quality and prestige. With the significant decline in student numbers since 2020, it has also become a serendipitous opportunity for those willing and able to go, since higher-ranking universities are now being much more accommodating to the reduced candidate pool. This is evident in the extended deadlines and reduced entry requirements being often observed.”

Ms Eklund’s observations highlight that competition for Chinese students is intensifying, and even Chinese families who are able to fully fund their children’s education may be receiving offers of scholarships and other incentives that they might not have expected before the pandemic. Keeping an ear open to what’s working in local Chinese cities and regions and working closely with experienced agents could help to identify the strategies that could provide institutions with a key edge over the competition.

For additional background, please see: