Tracking reported and projected higher education enrolment through September

- The recovery from the COVID-19 crisis will be measured in years, and the baseline for that recovery will depend in part on actual higher education enrolments through the balance of 2020

- The work of gathering that enrolment data is underway, including some early indicators from the United States and Canada

As the pandemic began to take hold early this year, it quickly became clear that the severity of its impact would depend greatly on how long it continued into 2020 or even 2021.

The academic year in Australia and New Zealand was immediately disrupted in the first quarter of 2020. And, as we moved into the second quarter of the year, institutions and schools throughout the northern hemisphere suspended in-person instruction and pivoted to online delivery.

One of the pressing questions at that point was how severely language travel programmes would be affected over the peak summer season. The answer is now all too clear with some destinations projecting enrolment declines of 80% or more for 2020.

It seems clear now as well that the recovery from the COVID-19 crisis will be measured in years. Along with language travel numbers, the baseline for that recovery will depend on actual higher education enrolments through the balance of 2020. The work of gathering that data is already well underway, and sufficiently so that we can consider a couple of early indicators here.

US community colleges under pressure

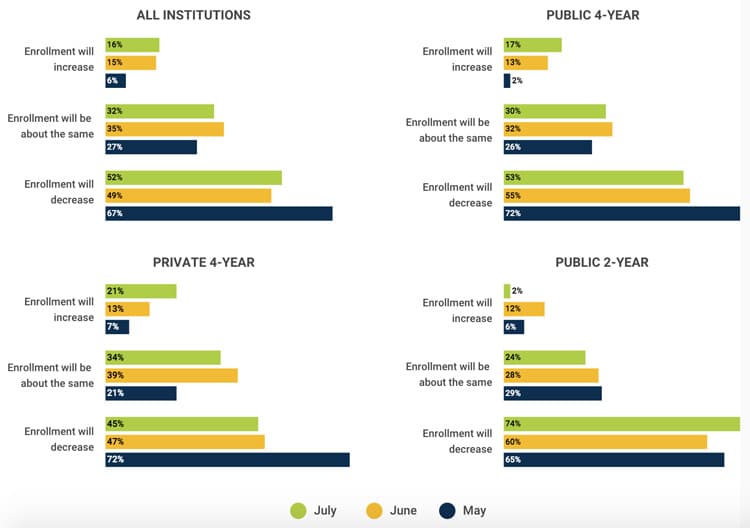

The American Council of Education (ACE) is conducting a series of pulse surveys, and has published results from the May, June, and July survey cycles.

The surveys go out to college and university presidents throughout the United States, and there are some interesting patterns to be observed in the thinking of institutional leaders over the three reporting months available to this point.

As the following charts illustrate, the expectations of college and university leaders with respect to fall enrolment became somewhat more optimistic from May through July. More than half still expected that fall enrolment would decrease as of July, but that compares to the 67% that expected an enrolment drop as of May.

The other variable that jumps out in these early survey results is that the most pessimistic outlook is for public two-year institutions, which are commonly referred to as junior colleges or community colleges. As of July, nearly three in four presidents expected that their college enrolments would decline in the fall. Also notable is that the survey outlook was worse among two-year colleges in July than was the case in May.

The reasons for the declining outlook for two-year colleges are not entirely clear but some of the factors appear to be that most of these institutions (92% as of this fall) are continuing with online delivery. Most also offer shorter-term programmes, and many of those focus on applied learning, which may not always translate as well to online delivery.

The outlook for Canada

This pattern is also playing out to some extent in Canada, where a large number of colleges and universities have also now reported on actual or expected enrolments for fall.

Consultant and futurist Ken Steele has compiled these reports into a detailed summary on his Eduvation blog, and again there are some clear trends emerging in those figures.

Mr Steele notes that, as in the US, community colleges in Canada are seeing significant downward pressure on both domestic and international numbers. Applied programmes at these institutions, many of which (a) are one-to-two years in duration and (b) rely on some level of hands-on learning, are especially vulnerable during the shift to online learning this year.

A number of colleges in Ontario with large international programmes, for example, are projecting significant enrolment drops this fall, including Georgian College (-24%), Humber College (-40%), Sheridan College (-42%), and St Clair College (-50%).

Similarly, those universities that have publicly reported projections for the year ahead are anticipating significant declines in international numbers, typically ranging from -20% to -50%. Some have put a dollar value on that decrease as well, with the University of British Columbia anticipating a CDN$76 million shortfall in international tuition revenues for the 2020/21 academic year, and Thompson Rivers University forecasting a CDN$20 million drop in international tuition.

More broadly, Mr Steele observes that larger research institutions may have an advantage in terms of attracting domestic students this year, while, ironically, some smaller institutions that emphasise more the quality of their campus communities or student experience may be at more of a disadvantage. "It wouldn’t surprise me if the big winners in domestic enrolment were top research universities like [University of Toronto], [University of Waterloo], [Western University], and [University of Saskatchewan]," he says. "Far-flung Canadian undergrads see an opportunity to attend a big brand institution without leaving home, and may even assume that larger institutions have better-developed online offerings." Meanwhile, "It appears as though many of the universities struggling with domestic enrolment this fall are those that have always prided themselves on their campus experience (like Acadia, Brandon, Bishop’s and [Mount Saint Vincent University])."

For additional background, please see:

- "Recruitment reset for 2020/21: Focus on content and agents”

- "Early lessons from the pandemic: New products and the power of partnerships”

- "Looking ahead: Scenario planning and recovery forecasts for international education”

- "Coronavirus update: Economic and mobility impacts will depend on how long the outbreak persists”