Coronavirus update: Economic and mobility impacts will depend on how long the outbreak persists

Despite the efforts of the Chinese government to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, which the World Health Organisation (WHO) has now named Covid-19, there has been a sharp increase in the death toll from the virus as well as more cases, and centres of transmission, in countries other than China. There have been more than 43,000 confirmed cases in China since December, tens of thousands more suspected cases, and more than 1,000 deaths. Almost all fatalities have occurred in Wuhan and in the surrounding area of Hubei province.

Experts do not believe Covid-19 has reached its apex, but already, the outbreak has profoundly disrupted student mobility as a result of travel restrictions, voluntary or enforced quarantines, and cancelled exchange programmes.

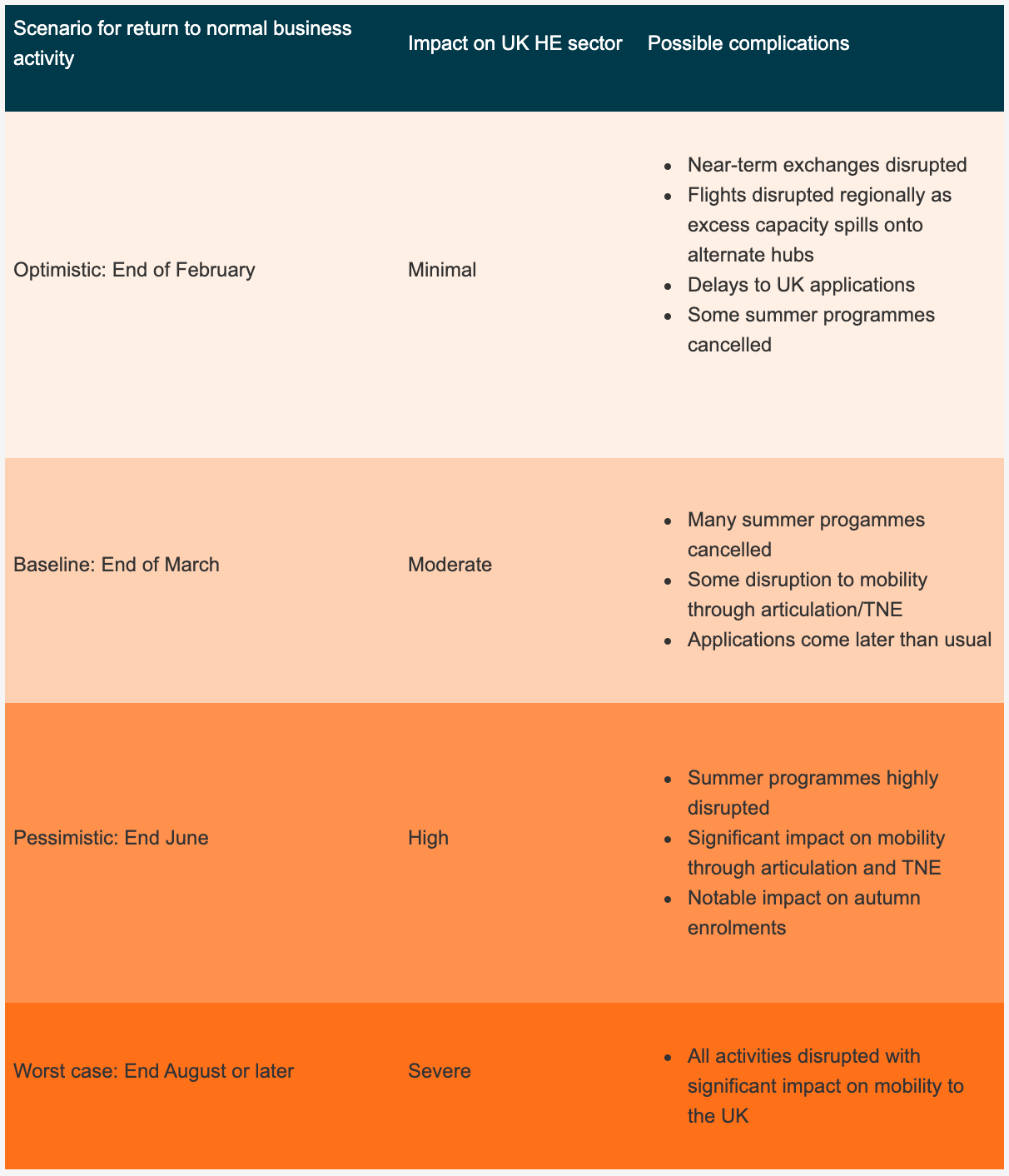

The following table, published by the British Council, shows how enrolments could be affected depending on how long the outbreak continues. ELT providers in particular – especially in destinations such as the UK that enrol high proportions of short-term junior students – are concerned that summer group programmes may be jeopardised if the outbreak persists through mid or late March.

The current situation

Al Jazeera has documented cases of the new coronavirus outside of China as of 11 February, including 15 in Australia, 16 in Germany, 11 in France, seven in Canada, 28 in Japan, 18 in Malaysia, 47 in Singapore, 28 in South Korea, 18 in Taiwan, 33 in Thailand, 15 in Vietnam, eight in the UK, and 13 in the US. There are also hundreds of confirmed cases of the virus – spread among multiple nationalities – on cruise ships docked in various ports around the world.

In the UK, the government has declared Covid-19 “a serious and imminent threat to public health.” Cases of the virus doubled over the weekend in the UK and two of the ill are healthcare workers; the number of patients and staff who may have been in contact with those two workers is not yet known. On 10 February, the government announced new powers to forcibly quarantine people suspected of having the virus, if needed.

There are now confirmed cases of the coronavirus amid international student populations outside of China including Canada, the UK, and the US.

In Australia, where more than a hundred thousand Chinese students enrolled in universities have not been able to come back to the country after travelling home for Lunar New Year celebrations, universities could face significant losses in the current semester.

Suffice to say that this week, levels of concern about fatalities; the virus’s spread; social ill-effects including xenophobia, anxiety, and depression; the global economy and national economies; and the industries that stand to be most hurt by the illness – have risen.

In the context of SARS

Much is not yet known about when and how the Covid-19 virus will begin to slow down, but what we do know is that:

- There is not yet a vaccine for Covid-19. Though experts believe that a “viable” vaccine will begin to be tested on humans by summer 2020, it will take at least a year for a vaccine to be developed that is considered safe and effective enough for widespread use.

- At this stage, the vast majority of deaths from Covid-19 have occurred in China, while deaths from SARS were reported in more than two dozen countries.

- SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) was also a coronavirus and killed 774 people over several months in 2002 and 2003. The death rate for SARS (9.6%) was far higher than it currently is for Covid-19 (which stands at roughly 2% as of February 2020), but because Covid-19 has made so many people sick it is spreading more quickly and thus the total number of deaths has already surpassed those reported during the SARS pandemic.

- Another difference between SARS and Covid-19 is that the average incubation period for SARS was seven days; for Covid-19 it appears to be at least 14 days and possibly up to 24.

- By far the majority of people who have contracted Covid-19 are in the Hubei area of China. In addition, the vast majority of people who come down with Covid-19 experience relatively mild symptoms.

- Eventually Covid-19 could become an “endemic” coronavirus that comes and goes in seasonal outbreaks. There are four other coronaviruses currently circulating that cause up to one quarter of all cases of the common cold.

The economic impact

At this stage, no one knows just how much the virus will affect the global economy. We know that tourism-dependent destinations (e.g., Thailand) are already suffering and that factories and operations for many of the world’s biggest manufacturers have been seriously disrupted.

The fact is that the Chinese economy is larger and far more integrated in the global economy than it was at the time of the SARS pandemic of 2002/03. And, as all our readers are aware, the international education industry is highly reliant on student outflows from China. The number of Chinese studying abroad in various destinations has grown from less than 150,000 in 2002/03 to over 662,000 as of 2018. Chinese now make up at least a quarter of all international students on campuses in the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Japan, New Zealand, and South Korea.

Whether Covid-19 will cost economies, and our industry in particular, more than SARS (which inflicted billions of dollars of damage) depends on when (and if) the virus’s spread and lethality can be brought under control. According to the Financial Times, Morgan Stanley has issued the following estimates:

“If work resumes on 10 February, the hit to global growth is forecast at around 15 to 30 basis points during the first quarter. A gradual return to work as migrant workers and logistics face challenges could limit growth by 35 to 50 bp and an extended disruption where the outbreak does not peak until April, could see a 50 to 75 bp hit for the first quarter and a 35 to 50 basis point hit for the first half of 2020. In the near term, there are still uncertainties as to how quickly the coronavirus situation will be brought under control and when production and goods transportation services will be ramped up to normal levels.”

Editor’s note: a basis point is equivalent to .01% (1/100th of a percent). To put the above projections in context, global growth was expected to be 3.2% in 2019. The high end of the estimates given here would see worldwide growth reduced by as much as .75% – or roughly one quarter of total growth for the year.

If we look back to SARS and its impact on international education, we can see that it depressed Chinese outbound immediately and for some time. For example, there was a nearly 5% drop in Chinese enrolments in the US in 2003 (during and immediately after the SARS outbreak). The number then recovered very slowly over the next two years (1.2% growth in 2004; .1% in 2005) before resuming more robust growth in 2006.

The fallout from SARS for international educators was a result of:

- Greater reluctance to travel because of public health concerns;

- Decreased ability of Chinese families to fund study abroad because of economic fallout from the pandemic;

- Disruption in marketing and recruitment activity on the part of agents and foreign educators because of the outbreak.

We could reasonably expect this same pattern to play out around the current outbreak, with the obvious caution that it is too early to measure the true scale of the impact of the coronavirus.

Australian universities adopting various strategies

UNSW Sydney vice-chancellor Ian Jacobs told Times Higher Education, with reference to Covid-19, that “things could be worse.” He continued,

“This is likely to [last] for a fixed time until it is safe to remove the travel restrictions, and we will plan accordingly. There are a variety of ways any sensible organisation would deal with this sort of issue. In some ways it’s good to be tested, not that we would have asked for this.”

Professor Jacobs pointed to the flexibility in the Australian university calendar as being a potential game changer in terms of how much Chinese students, and the sector itself, is affected:

“[The trimester-based calendar] means that instead of having just two entry points to our programme, we have three. We have a timetable that was deliberately designed to allow flexibility. [For] those who can’t arrive on 28 February it’s not a big problem because they can enrol for term 2, which commences on 1 June. They will be able to cover the courses they’ve missed and graduate on time as planned.”

UNSW established a “future fund” several years ago to have on hand in case of emergencies such as Covid-19, a fund Professor Jacobs says is designed “to give us enough time to put in place a long-term plan if we need it.”

THE further reports that across the university sector in Australia, there are a variety of approaches to minimising the impact of Covid-19 for students, from deferred start dates to more online/off-campus learning modalities.

Weeks ago, The Australian predicted that the cost of Covid-19 to Australia’s international education sector might be up to AUS$8 billion (£4.1 billion), “taking into account tuition fee refunds, accommodation costs and the need to reorganise teaching calendars.”

As in Australia, institutions and schools in other study destinations are also having to quickly come up with protocols as a result of Covid-19, including suspending student exchanges and study abroad terms due to begin this month. Michael Schoenfeld, a spokesman for Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, told Bloomberg News that,

“You’d be hard pressed to find a major US university that doesn’t have some form of engagement in China. If you’re a global institution and you’re not prepared for something of this scale, you’re going to have to get there.”

For additional background, please see: