Mapping the trends that will shape international student mobility

A new British Council report sets out the key trends that are shaping both higher education demand and international student mobility. “We are at a tipping point in the global higher education system. Students have more choices than ever,” says the British Council’s Director Education Rebecca Hughes. “Beyond and behind traditional student recruitment lie drivers of change that are shifting the very nature of how we view and deliver higher education: they are indicative of a larger movement in the education sector, in line with an uncertain and rapidly changing future.”

The full report, 10 trends: Transformative changes in higher education outlines the ten global trends that the authors have judged will have the greatest impact on higher education in the future.

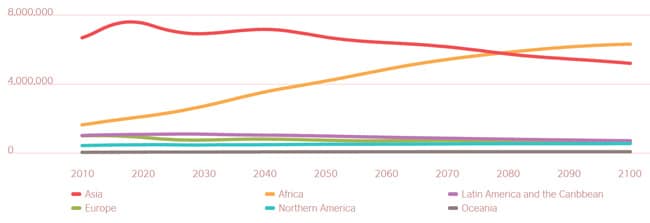

These include some major shifts in demographics around the world. The British Council highlights in particular the influence of ageing populations in many regions. Simply put: greater life expectancy combined with lower fertility rates means that populations in many countries are getting older, and, in the process, the key 15-to-24-year-old college-aged cohorts are shrinking.

Putting a priority on recruitment

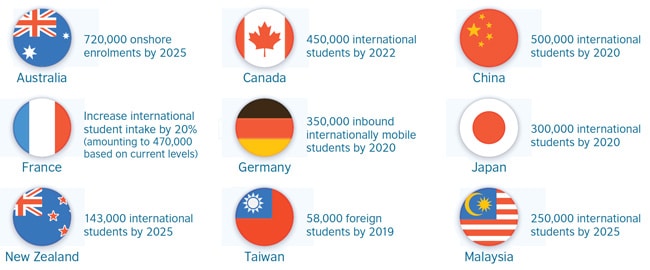

The British Council also highlights the growing prominence of national strategies for international education, among both established and emerging study destinations.

Increasingly, these plans are focused on increasing the country’s market share in terms of internationally mobile students. They are also often closely integrated with broader national strategies for trade and economic development, including, for example, programmes to promote skilled migration and close domestic labour market gaps.

Weakening brand influence?

There is a great deal more to be said on this subject, but the report raises the question as to whether elite institutional brands will have less influence on student choice in the future. Really, the observation that is being made here is that students and families appear to be placing more emphasis on value and, in particular, on the return on investment of an overseas education. At the same time, there are growing indications that major employers are placing less emphasis on educational brands – for example, via greater openness to non-degree credentials or by adopting so-called “blind” hiring processes that exclude school-specific information. We have seen other indicators of this in recent research that points to a greater emphasis on subject-level rankings and career outcomes, and, even more broadly, to the importance of unbranded search in the student decision-making process. It appears too in the price sensitivity exhibited by some students that, while drawn to elite brands or leading study destinations, are also clearly open to other choices.

The lingua franca

The 10 trendsreport points out that English has become an important lever for international student mobility. This is reflected in global demand for English language learning, but also in the rapidly expanding field of English-taught degree programmes in non-native-English-speaking destinations. The report adds: “English language provision also plays an important role in mobility, as the language acts as a draw for international students. Further, the language can be a pathway for future mobility as well, as students studying English in a host country tend to return to that country when pursuing overseas study.” But questions abound as to how this pattern will continue to play out. How will institutions and educators adapt over the long term to the linguistic and pedagogical challenges of teaching in a language other than their native language? And what role will technology play, particularly with regard to online learning and the rapidly improving systems and tools for both language learning and near-simultaneous translation? It is hard to imagine a future where English does not continue to play a major role in international mobility, but the authors leave room for this possibility as well: “As attention towards digital literacy increases, there is potential for English language literacy and programmes to take a backseat as a new lingua franca emerges.” For additional background, please see: