English-taught programmes in Europe up more than 300%

While Europe comprises nations with diverse policies and goals, the desire within the education sector to increase international mobility among students is a widely shared objective. A recent study written by Bernd Wächter and Friedhelm Maiworm published by the Academic Cooperation Association (ACA) collected survey data from European education institutions to examine their use of programmes taught in English as a tool to increase mobility. Data collected by ACA in collaboration with the Gesellschaft für Empirische Studien (GES) and StudyPortals BV shows that the number of English-taught bachelor and master programmes – referred to in the study as English-Taught Programmes (ETPs) in non-English-speaking European countries has more than tripled over the last seven years.

A massive surge in ETPs

Comparing data from earlier studies shows how widespread the adoption of ETPs has become. The number of English-taught programmes was counted as 725 in 2001, 2,389 in 2007, and according to the present study, 8,089 in 2014. The new data, as well as that from other sources - such as that included in a 2013 ICEF Monitor article - attests to the accelerated introduction and delivery of ETPs across Europe.

Currently, Germany has the largest number of institutions offering such programmes, at 154, followed by France with 113, and Poland at 59.

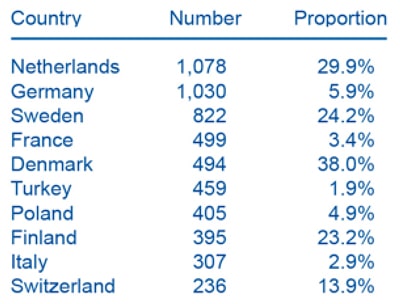

In absolute terms, the Netherlands has the most ETPs with 1,078, followed by Germany with 1,030, and Sweden with 822.

The chart below shows the top ten countries for ETPs numerically, and the proportion within the total number of programmes available.

A look inside the classroom

ACA tracked the student mix in these courses, and found that 54% of the total were foreign students in the nations in which they are studying. In the 2007 survey that percentage was much higher, at 65%, and in the 2002 survey the percentage was 60%. The reasons behind this 11% drop in foreign enrolment over the seven years is not entirely clear, but could be a reflection of economic factors in Europe. However, there is still international diversity in the programmes. As few as 5% of the ETPs surveyed reported only domestic students enrolled. At the opposite end, 10% of ETPs stated that all the students were from outside their own country.

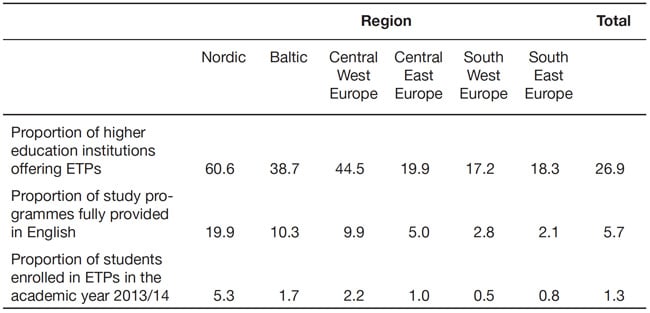

Comparatively speaking, ETPs in the Baltics and in Southeast Europe tend to enrol domestic students, while those in the Nordic region and Central West Europe enrol more foreign students.

In terms of classroom make-up, the survey found that students from Europe formed by far the largest cohort in European ETPs. Below is a breakdown of students’ regional origins:

Respondent expectations and motivations

While English language instruction is known to enable greater student mobility, survey respondents were asked to dig deeper and give specific reasons why they had adopted ETPs as a means of boosting internationalisation at their institutions. Essentially, these questions probed expectations, and charted reported effects. Some of the responses were as follows:

- To do away with language obstacles for foreign students – i.e., to attract those who won’t enrol in a programme taught in the country’s domestic language;

- To improve international competency of domestic students – i.e., to increase diversity at the institution, foster intercultural understanding, and better prepare students to be globally competitive;

- To raise the international profile of the institution;

- To attract top talent at both the student and staff level;

- To provide high-level education for students from low-income countries as a means of development aid;

- To compensate for shortages at the institution – i.e., to counterbalance a lack of enrolment by domestic students and/or to generate revenue from tuition paid by foreign students.

The survey notes that in general, revenue as a motive was cited least often, whereas altruistic considerations - for example in the area of development cooperation - played a surprisingly strong role. The ACA survey also asked institutions their reasons for not adopting ETPs. Typical responses were:

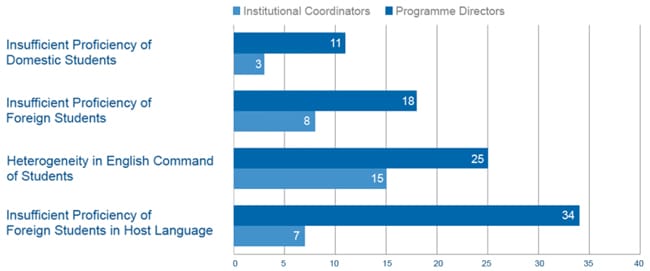

- Language proficiency issues – low levels of English among teaching staff and/or among domestic students; or, on the other hand, high proficiency of foreign students in the domestic language.

- Type of higher education institution and/or discipline – English was deemed unnecessary, difficult to introduce, or incompatible with the discipline taught, for example music or the arts. Conversely, some institutions offer programmes with specialised terminology students needed to master in the domestic language, as is the case in teacher training or law.

- Insufficient international enrolment and/or lack of interest among foreign students.

- Contractual considerations – some institutions have established bilateral agreements with foreign institutions stipulating that incoming students master the domestic language.

- Legal obstacles, for example arising from regional autonomy agreements, such as in Spain, which create difficulties designing study programmes; accreditation issues also exist in some countries, such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

- Lack of resources.

Resources often relate to the size of an institution. Larger institutions have the ability to offer more programmes of all kinds than smaller ones, and are statistically more likely to offer programmes taught in English. The survey showed that in 2013/14, only 14% of institutions with 500 students or fewer offered ETPs, while 52% of institutions with 2,501 to 5,000 students offered them, and 81% of institutions with more than 10,000 students administered such programmes.

Programme effects

The ACA tracked the effects of ETPs upon schools. The most frequently cited effects were as follows:

- Improved international awareness of the institution (84%);

- The strengthening of partnerships with foreign institutions (81%);

- The improvement of assistance/guidance/advice for foreign students (71%), including the provision of information and services in English.

When asked in detail about the benefits to students, programme directors cited career benefits. Improved mastery of English in itself, apart from degrees earned, was believed to be a strong aid to future employment prospects. Respondents also cited as positives such as better networking opportunities thanks to a multinational student body, good preparation for international employment, and more mobility opportunities. Interestingly, many programme directors also believed that one strong benefit of ETPs was the closer interaction with teachers made possible by the generally smaller class sizes. Under such conditions, they believed students received more personalised guidance, which in turn enhanced the overall quality of their education. As a result of adopting ETPs, 56% of respondents attributed higher importance to promoting their schools, and to targeted recruitment of students in particular (54%). Institutions used a broad range of marketing measures and communication channels to reach students. The survey asked respondents to break their methods into two categories – those used by degree (i.e., methods used to attract bachelor students, as opposed to masters students), and those used according to target group (i.e., foreign as opposed to domestic students). Providing information via university websites was the most commonly used method in both cases, followed by distribution of printed material, presentations at domestic student fairs/information events, entries in international portals/databases, distribution of information via existing networks/partnerships of the institution, and presentations at foreign student fairs/information events. In both categories, the use of agents in target countries was among the least-used methods. The final study published by the ACA is a detailed document running more than 130 pages. It contains important details concerning collection methodology, before offering a large assortment of respondent data, along with the interpretations and conclusions of the authors.