Japan’s ambitious proposals for higher education and language sectors

Japan’s government is increasingly viewing education as a vehicle to drive economic growth. Its policies highlight internationalisation and higher education reforms, as well as new language and financing initiatives. After a difficult period, indicators may finally have leveled off, but a brewing political storm with China has the potential to change that. Today ICEF Monitor takes a look at the many forces affecting Japan’s education sector.

International students in Japan

Let's first set the scene by providing the latest top-line statistics on Japan as a sending and receiving market.

Japan has fared better of late in the area of inbound internationals than in recent years. The education sector experienced a drop after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake, tsunami, and subsequent radioactivity release at the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant. Another downward driver had been the Yen’s high exchange rate against the Korean Won, but 2012 numbers were close to those from 2011.

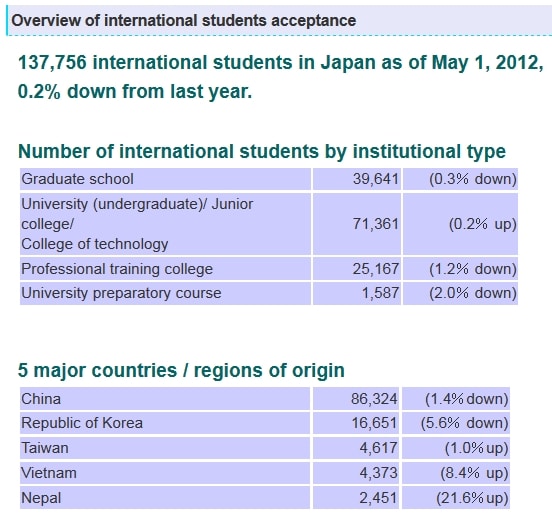

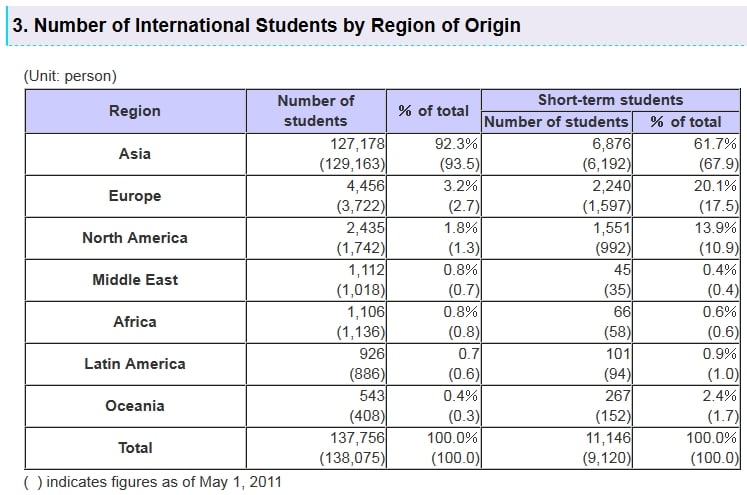

The Japan Student Services Organization’s (JASSO) most recent figures for university undergraduate, junior college, technical college, graduate, professional training college, and university preparatory course students studying in Japan as of 1 May 2012 are as follows:

Japan as a sending market

The number of Japanese students flowing overseas has declined in recent years. The downward drivers are multifold, and include a flat economy, graduate unemployment, and changing demographics. The latter is a particular concern, and puts Japan in the same boat as other Asian regions such as South Korea and Taiwan. But Japan’s demographic shift is the most severe of the group. Simply put, the Japanese government forecasts that the nation’s population could contract by 30% in the next half century, with negative effects in many areas of society, including international education. With Japanese citizenship and permanent residency still difficult for foreigners to obtain, there seems to be no easy way to bolster the country’s demographics. Consider data from one of Japan’s largest receiving markets: the United States. In the US, traffic from Japan fell from 24,842 in 2009-2010 to 21,290 just a year later, totaling a drop of 14.3%. And in 2012, Japan registered a 6% drop. With so many factors at work inside Japan, it’s safe to say this was not mainly a demographic decline, but certainly fewer Japanese students will not help the overall situation. However, nearby nations have seen more Japanese students arrive in recent years. Australia showed a 4.1% increase in Japanese student commencements in 2012, driven by growth in Australia’s vocational and English language education sectors. In New Zealand the number of Japanese students also rose in 2012, against an opposite trend of fewer overall student visa approvals.

Changes in the English Language Teaching (ELT) sector

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has proposed what he calls a “three-arrow” approach to educational reform aimed at improving science and math scores in order to produce more PhDs in those areas, focusing more on IT education, and bolstering the English skills of Japanese students. In the latter area, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) is pushing for regulations requiring students to achieve a minimum TOEFL score before acceptance to universities, and also before graduation. The proposal is aimed to shift the current system away from writing and grammar proficiency toward functional English, but it has caused considerable debate in Japan. Some opponents point out that even though more Japanese schools have already been offering TOEIC and TOEFL courses in recent years, students are not learning to speak English but rather to pass tests. They say the number of students who can successfully communicate in everyday English remains small, and is not likely to increase significantly even with minimum score requirements. Part of the difficulty stems from English teachers themselves possessing lower proficiency in the language than needed, however the proposals address this shortcoming by calling not just for students to reach benchmarks (45 points or higher on the TOEFL test) but for teachers of English to score 80 or higher. Hiring more foreign English speakers to teach the language has been suggested, but liberalising the current foreign teacher employment rules - under which native English speakers can be hired only as assistants, not full-time instructors - would likely be opposed by the Japanese teachers association Nikkyoso. However, a proposal from the LDP aims to double the number of teachers hired for the Japan Exchange and Teaching (JET) Program (from 4,360 in 2012 to 10,000) in three years. The teachers would be dispatched to all primary and secondary schools within ten years. And it’s worth noting that foreigners are finding Japan a more fertile job environment than during the country’s more insular past. Foreign students are filling more openings after graduation - 8,586 of them in 2011, as opposed to the 2,689 that obtained work visas in 2000. Some are finding integration and acceptance a challenge, but an expanded job market is good news for internationals. Whether a similar hiring influx looms for the English education sector is undetermined. Despite obstacles, Prime Minister Abe and LDP are pushing ahead with their reform package, which calls for ¥400 billion for English education restructuring. Pieces of the proposal will be included in LDP’s campaign pledges for the July 2013 Upper House election.

Shift in national enrolment schedule

One of the largest changes in Japanese education could be structural: universities could shift to a fall enrolment schedule. At the moment, the school year begins in April, which places Japan out of sync with international systems and may be yet another reason the country sends relatively few students overseas. The University of Tokyo (Todai), the top institution in Japan according to Times Higher Education rankings, is at the forefront of this radical idea. Todai President Junichi Hamada hopes to achieve the transition within five years, and perhaps earlier. But there are still obstacles, including the opposition of nearly 40% of parents with children up to 18 years old. Switching the system would be a huge undertaking, requiring a shift at all school levels from kindergarten up, and would involve giving students several months of potential idle time between April and September (on the upside, that time could be devoted to exchange programmes, summer camps, travel abroad, volunteering and internships). But the idea has momentum; the push by Todai has already caused Kyushu University and Kanazawa University to start discussions about a similar shift.

Initiatives in Japanese higher education

Under the Global 30 initiative, Japanese national universities pledged to lure 300,000 undergraduate international students to 30 schools by the year 2020, which would amount to 10% of the total student body. The original 2008 proposal was whittled down to 13 universities - all of which offer English-medium instruction - because of budget woes, but current government policies aim to expand the plan to 42 universities. If successful, this would be a massive influx of students, and recruiters should stay abreast of efforts to reach this goal. On the outbound side, the Global 30 Plus programme and the Reinventing Japan project are aimed at encouraging Japanese students to study overseas. Tomohiro Yamano, deputy director general of the higher education bureau at the Ministry of Education, told Time late last year:

“The ultimate goal is tied in with improving Japan’s economy. More specifically, for Japanese graduates to work for Japanese companies that will do business around the world and become more successful.”

Japanese universities are generally ramping up efforts in student exchange, international recruitment, and overseas collaboration. Government policies encourage double degrees with Asian and US universities, as well as promoting university networks, particularly in science and technology. And in order to bolster its sending numbers, Japan is funding short-term international studies for 10,000 Japanese university students. The government is also hoping the education sector receives a general boost in 2013 from a new Southeast Asia credit transfer arrangement to be adopted by all nations in the Greater Mekong Subregion (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and China, as well as Korea). In addition to the credit transfer agreement, Japan and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) have created what they call the ASEAN-Japan Plan of Action, a joint initiative designed to:

- implement education programmes to nurture entrepreneurs, seminars to strengthen human resource development, and training courses to study skills and know-how on international business within ASEAN;

- promote Southeast Asian studies, including Southeast Asian languages, in various universities and other educational institutions;

- establish human resource development centres in Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, and Vietnam to provide business education and Japanese language training;

- develop further educational exchanges under the ASEAN Universities Network (AUN) and the Universities Mobility in Asia and the Pacific (UMAP) initiative;

- expand access to basic education and improve the quality of education, recognising that basic education is the foundation of nation building.

Some other international linkages include:

- Earlier this year at the Abu Dhabi Japan Economic Forum, ten agreements and memoranda of understanding were signed between Abu Dhabi and Japan that impact upon the education sector.

- A new agreement was signed aimed toward African development, particularly in the education sector.

- Australia continues to look toward Japan for new education agreements.

Changes for domestic students

The Japanese government is looking at reforming its higher education sector via revised regulations that could limit the establishment of new universities and merge existing schools. With 75% of private universities falling short of enrolment targets, policy makers are focused on maintaining overall sustainability in the sector. Heightened competition for a shrinking pool of prospective students has prompted private universities to restructure summer campus visit programmes. For example, Osaka University of Economics and Law now pays ¥15,000 (US $192) to those who visit the campus from distant reaches of Japan such as Hokkaido and Okinawa, and even students who visit from much nearer Tokyo can receive ¥7,000. Meanwhile, at Hyogo University in Kakogawa, the ¥30,000 entrance exam has been discounted by one-third for candidates who visit the campus and complete other tasks. Universities are also making more effort to attract parents, such as touting job assistance programmes that could offset tuition costs. Another influence affecting Japanese students is the debt burden they take on to get a degree. About 960,000 - or one-third of current university students - are dependent upon public loans to finance their studies, and the amount of debt repayments in arrears hit ¥470 billion last year, mainly caused by joblessness and income drops during Japan’s extended economic slump.

Looming political difficulties with China

Perhaps the most important short-term factor for the Japanese education sector moving forward is an escalating territorial dispute between Japan and China over a set of uninhabited but oil-rich islands located in the East China Sea. Because family and parental views are a major factor in students’ choice of schools, especially in China, some sources expect the flow of applicants from China to fall dramatically in 2013. This may already be happening. Hitoshi Iwamoto, Director of Fukuoka Foreign Language College, told Study Travel magazine that a third of Chinese students that had enrolled in courses scheduled to commence in October 2012 cancelled. October was the last period from which the Japanese government has made student visa data available. But Iwamoto has said that applications for April programmes are 80% lower than expected. A decline in numbers that large from Japan’s largest sender of international students would be disastrous, but so far neither side is backing down in a dispute that has seen Japanese nationalists, Chinese marine surveillance vessels, and Japanese coast guard cutters all plying the same waters. In addition, the dispute reached an alarming pitch when Japanese Prime Minister Abe vowed to use force if necessary.

Japan as a bellwether

Japan faces challenges on numerous fronts, but positive changes have taken place. Many observers see the country as the “canary in the coal mine” for other industrialised nations, some of which are seeing the same demographic trends take hold, if to a lesser degree. Japan will be closely watched as a case study of how to manage such issues, and which strategies lead to successful outcomes.