The state of international student mobility in 2015

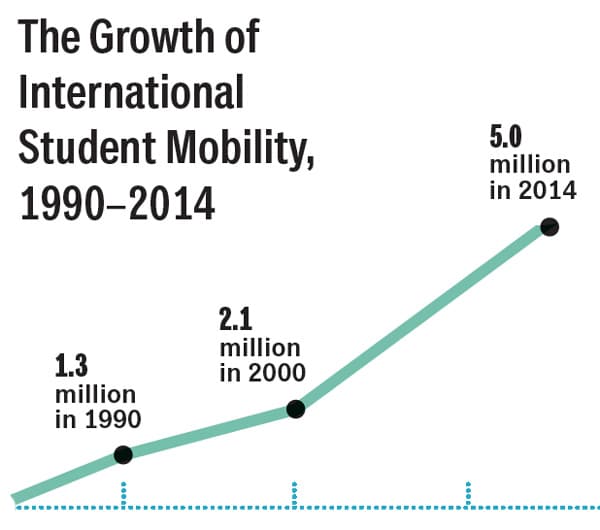

As you read this, five million students are studying outside their home countries, more than double the 2.1 million who did so in 2000 and more than triple the number in 1990. This astounding growth has occurred in the context of an increasingly globalised world in which economies are closely tied to others within their region and beyond. In 2015, money and trade are flowing freely across many borders and from many sources. So, too, are knowledge and skills.

Once accessible only to the world’s elite, higher education is now open to the masses, particularly the burgeoning middle classes now found on every continent. And especially in countries lacking higher education capacity, students are looking for opportunities to study abroad.

Asia is the key

Take, for example, the ascendance of China and India into the top ten most powerful economies in the world; South Korea is in the top 15. Now consider their contributions to international student mobility: China, India, and South Korea are the world’s leading sources of international students. One of every six internationally mobile students is now from China, and together China, India, and South Korea account for more than a quarter of all students studying outside their home countries. All told, 53% of all students studying abroad today are from Asia. Asia is also becoming a compelling destination for international students, particularly those from within the region. China, for one, has drawn increasing numbers of both Indonesian and Korean students in recent years. The number of Indonesian students in China has grown by an average of 10% each year since 2010, and nearly 14,000 Indonesians are currently studying in China. Meanwhile, the number of South Koreans studying in China more than doubled from 2003 to 2012. Overall, China hosted about 330,000 students in 2012 and has a target to reach 500,000 students by 2020. Japan, pressed to respond to excess capacity in its universities, is also stepping up its recruitment of international students; it has a goal of hosting 300,000 international students by 2020. Japan saw foreign enrolments increase nicely in 2014. Malaysia is similarly ambitious, with a goal of 250,000 international students and plans to place several more of its universities in world rankings by 2025. Today, 24 of the world’s top 200 universities in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings (2014/15) are Asian - representing almost one-eighth of the total.

The call for diversification

In recent years, a staggering number of international students in the US, Canada, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand have come from China and India, a heavy reliance on these two key markets that has raised alarm bells for some institutions and industry experts. International educators are thus being encouraged to diversify their international enrolments - and they have a ready supply of other sources to consider. African countries are struggling to meet demand for higher education as their youth populations swell and unemployment abounds. Many are investing heavily in building more capacity and quality into their tertiary systems, but such initiatives do not bear results overnight. In the meantime, study abroad is a tempting option for those students who can afford it. Particularly in fast-growing African economies like Nigeria, outbound student mobility is on the rise; according to UNESCO, over 52,000 Nigerian students studied abroad in 2013. Nigeria is on pace to be one of the world’s most populous countries and it has a swiftly growing tertiary-age student cohort. The impact of this population surge will be huge: The British Council recently projected that of the 23 source markets it studied, Nigeria will contribute the strongest average annual growth in post-graduate student mobility through 2024 (+8.3%). International educators are also viewing Latin American markets with great interest, thanks again to rising youth populations, lagging domestic capacity, and scholarship programmes. In 2011, 20% of the total population of Latin America and the Caribbean was between the ages of 15 and 24 – that’s 106 million people, and the UN notes that this is "the largest proportion of young people ever in the region’s history." As in so many other countries with swelling youth populations, the challenge is to expand educational access and reduce unemployment, with the ultimate goal of empowering this generation to achieve a better quality of life and to drive the economy forward. Until the region’s higher education institutions become more accessible and of higher quality, students will be especially interested in study abroad.

Growing demand for post-graduate education and VET

The recent "massification" of higher education, in which higher education became accessible to more of the population, is driving a new trend: greater numbers of university graduates are now also able to pursue post-graduate studies. The British Council expects India and China to contribute the greatest number of globally mobile post-graduate students in 2024, but notes that demographic and economic trends will see Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Indonesia posting "substantive increases in outbound post-graduates." Something to watch through 2024 will be the extent to which increased capacity and quality at home, particularly in key sending markets, will affect outbound post-graduate mobility. Case in point: the number of Chinese post-graduate students applying to US universities declined for the third consecutive year in 2015, a fact believed to be partly due to China’s massive investment in its own higher education capacity for both graduate education and research over the past decade and more. Similarly, the sharp rise in demand for “middle skills” taught by vocational education and training (VET) institutions around the world through certificates, diplomas, and other short-term programmes could also affect demand for post-graduate (and undergraduate) programmes. Nearly two-thirds of overall employment growth in the European Union is forecast to be in the "technicians and associate professionals" category, while in the US, nearly one-third of job vacancies in 2018 are expected to require some post-secondary qualification but less than a four-year degree. China, India, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and Thailand have all recently increased their budget allocations to vocational training, and demand for VET is also surging in Africa.

Where they will go

Demographic trends, economic growth, government scholarships, and rising incomes are some of the major forces at play in determining where students are coming from when they study abroad. But what about where they are going? The answer to this question involves the interplay of different factors. On the one hand, students’ own circumstances guide their choice of where to study (e.g., their financial means; the level of study they are pursuing; the advice they receive from friends, family, and agents; their perceptions of the image and reputation of an institution or country). On the other hand, country-level and institutional policies affect the popularity of destinations. Students are often influenced by the relative cost of living and tuition in a country (which may be affected by currency fluctuations) as well as the availability of internships and post-study work and immigration opportunities. Scholarship programmes play an important part as well. The past decade has seen the development of several massive scholarship and grant programmes, notably Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah Scholarship Programme (KASP), Brazil’s Science Without Borders, and, more recently, Mexico’s Proyecta 100,000. Large-scale regional programmes, of which Europe’s Erasmus+ is the most prominent example, also play a major role in driving mobility. In 2015, the US is still the world’s leading destination, and it is expected to enrol a record number of students again this year. But America’s market share is falling (from about 23% of all internationally mobile students in 2000 to 17% in 2011). This change is partly due to the increasing share of other English-speaking destinations such as the UK, Australia, and Canada, and partly due to the growing trend toward intra-regional mobility. Market share aside, the OECD reports that in 2011, "almost half of all foreign students were enrolled in one of the top five destinations for tertiary studies abroad: the US, with 17% of all foreign students worldwide, followed by the United Kingdom (13%), Australia (6%), Germany (6%) and France (6%)." Those statistics reflect 2011 OECD data, yet so much has happened since then. Australia, for example, experienced double-digit growth in international student enrolments in 2014. Canada’s international student population increased 23% from 2011 to 2013. In contrast, following a tightening of work and immigration rules in the UK, British higher education institutions saw overseas enrolments fall in both 2011/12 and 2012/13.

Looking ahead

At this writing, most students who choose to study abroad choose OECD countries as their destinations. But as linkages and trade intensify between Western economies and Asian ones, and as Asian countries expand and improve their higher education systems, we will likely see mobility patterns become more diverse over the next decade. Top American and British institutions still attract the majority of the world’s most ambitious and/or wealthy students, but Asian countries are climbing steadily up world university rankings. As competition increases for students, we can expect to see countries and institutions differentiate themselves using a range of strategies, including destination marketing, branding, tuition and/or financial assistance, and (at the country level) work and immigration policies. International education is no longer a niche area of the economy or the pursuit of a small segment of lucky students: it is measured in millions of study visits – and billions of dollars. The sector has come a long way in a relatively short time, and if stewarded responsibly by governments, associations, institutions, and agents alike, it will go much further.