Four trends that are shaping the future of global student mobility

Every now and then, we find it helpful to step back from the steady tide of market reports and information and think about some of the larger trends that are influencing international student mobility. Here are four that are likely to have a profound impact on global education markets for the next decade and more.

1. Growth will continue, but at what rate?

The estimates have it that there are about five million students studying outside of their home countries today. This represents an increase of nearly 67% from the three million students that did so in 2005, with average annual growth of 7% per year between 2000 and 2012. The OECD projects that the world’s population of international students will reach eight million by 2025. This represents a slightly cooler, but still very impressive, projected growth rate of 60% in overall global mobility over the next decade. The big question is what happens after that. It is fair to say that domestic higher education capacity has been an important driver of growth in recent decades. Simply put: in countries that lack higher education capacity – whether in terms of available seats or reliable quality of education – students look for opportunities to study abroad. But that domestic capacity question is shifting in many key markets, and will continue to do so. "Up to 2002, more students were enrolled in higher education in North America and Western Europe than in any other world region. But since 2003, there have been more students pursuing higher education in East Asia and the Pacific," wrote RMIT University analyst Angel Calderon in a 2012 article for University World News. "The East Asia and the Pacific region is expected to exceed enrolments of 100 million students between 2020 and 2021 and to exceed enrolments of 200 million between 2033 and 2034." More recently, Mr Calderon noted in a pre-conference briefing for EAIE 2015 in Glasgow, "Higher education participation rates will continue to rise…meaning that demand for previously unmet domestic higher education will be met for countries such as China, India, Brazil and Indonesia." More to the point, he notes that major sending markets, such as China and India, still have an unmet demand for tertiary education that amounts to about 30 million young people each. But "once that capacity is met, somewhere around 2025, international student mobility may reach a game-changing moment."

While there are many factors that act on global demand for study abroad, the implications of this demand-supply shift are potentially profound.The changing undergraduate-graduate composition of Chinese enrolment in the US

can be seen as an early indicator of how such shifts can directly influence patterns of student mobility. Needless to say, the prospect of slower growth over the long term, particularly from today’s key source markets, carries with it some important strategic implications for international educators going forward.

2. Leading destinations losing share

The US remains the world’s leading study destination, and, together with the UK, Germany, France, and Australia, hosts about half of the world’s mobile tertiary students. Many of these leading destinations, however, are losing market share in recent years. The US share of internationally mobile students dropped from 23% in 2000 to 16% in 2012, even as the absolute number of foreign students in America continues to climb. The UK, where enrolment has flattened in recent years in the face of more restrictive visa policies, has lost ground as well. This shift is largely a function of increasing competition among destinations. Both Canada and Australia have gained a greater share of international students over the last decade. But other countries have also gained ground. The OECD reports that outside of these leading destinations, "significant numbers of foreign students were enrolled in the Russian Federation (4% market share in 2012), Japan (3%), Austria (2%), Italy (2%), New Zealand (2%), and Spain (2%)." Add to this the growing impact of emerging regional hubs for education – more on which below – and it is fair to say that the stage is set for a new level of competition among leading study destinations over the next decade and more.

3. Middle class driving growth

The growth of the middle class in emerging economies around the world is another key factor in overall demand levels for study abroad. As Dr Simon Marginson wrote earlier this year, "The number of middle class people in Asia is expected to rise from 600 million in 2010 to more than three billion in 2030 [and] middle class families want tertiary education for their children."

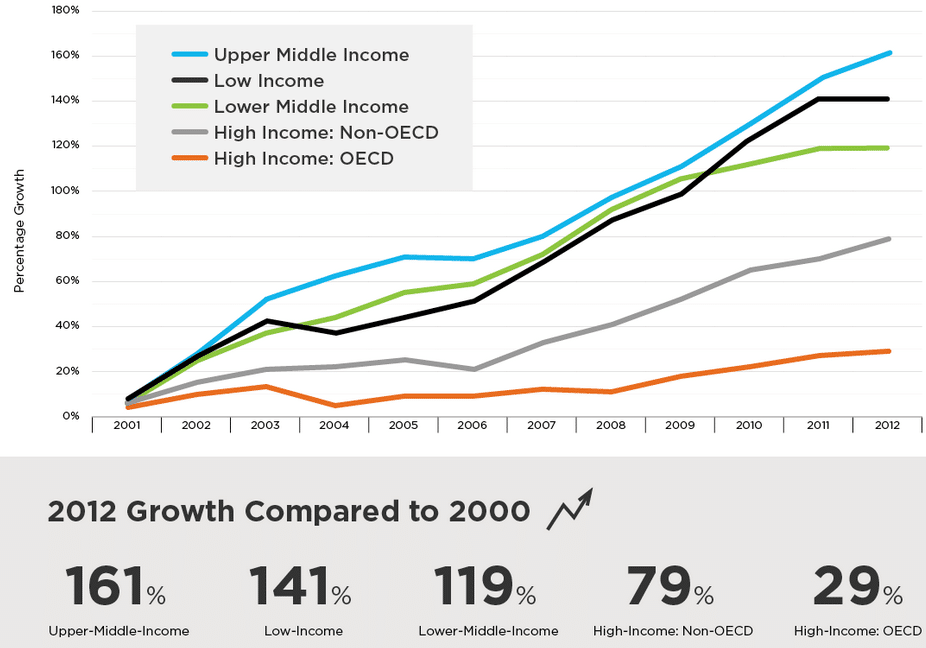

A recent World Education News and Reviews (WENR) analysis expands on this point by highlighting that growth in outbound mobility since 2000 has been heavily influenced by the expansion of the middle class: "Upper-middle-income economies…are the ones driving growth in outbound student mobility. The total number of outbound international students from upper-middle-income economies jumped 161% between 2000 and 2012, as compared to only 29% from high-income OECD countries."

4. Regional student mobility

The Education at a Glance 2014 report makes the point that: "Global student mobility follows inter-and intra-regional migration patterns to a great extent. The growth in the internationalisation of tertiary enrolment in OECD countries, as well as the high proportion of intra-regional student mobility show the growing importance of regional mobility over global mobility." We have been tracking the increasing role of intra-regional mobility in recent years. For example, the pattern is clearly visible in UNESCO statistics that indicate the percentage of Latin American students remaining within the region increased from 11% in 1999 to 23% in 2007. Similarly, the percentage of mobile East Asian students studying within the region rose from 36% to 42% over the same period. This trend is further supported through a growing number of regional mobility schemes around the world, such as those among the ASEAN countries and of course the landmark Erasmus programme in Europe. But also of note here are an increasing number of bilateral mobility arrangements, including Mexico’s Proyecta 100,000 initiative and the corresponding 100,000 Strong in the Americas programme for US students. Finally, intra-regional mobility is also supported and extended via a series of regional hubs: emerging study destinations that are explicitly expanding capacity but also actively recruiting abroad, and especially so within their respective regions. The emerging patterns of increasing regional mobility that result from all of these factors are an important trend in international education today and, we expect, will be a key determinant of the competitive landscape of tomorrow.