Chinese enrolment in the US shifting increasingly to undergraduate studies

Chinese students are flocking to American higher education institutions. According to the latest Open Doors data from the Institute of International Education (IIE), 274,439 students from China studied in the United States in 2013/14 for an increase of 16.5% from the previous year. That was also the fifth consecutive year in which Chinese students were the largest national group among America’s international student population in 2013/14 (composing 31% of the total). And increasingly this growth is being fueled by a massive surge in the popularity of American undergraduate programmes among Chinese students and their families.

Growing undergraduate demand

The latest Open Doors data reveals that the flow of Chinese students into US undergraduate programmes is speeding up at the same time as demand for American graduate programmes (the historic core of Chinese enrolment in the US) has been slowing. Chinese students at the undergraduate level in the US now number 110,550 – very close to the 115,727 students enrolled in graduate studies in 2013/14. The breakdown by category of study that year was:

- 40.3% undergraduate;

- 42.1% graduate;

- 12.2% OPT (Optional Practical Training);

- 5.4% other.

This represents a significant shift from the year 2000, when there were six Chinese students enrolled in US graduate programmes for every Chinese undergraduate in America.

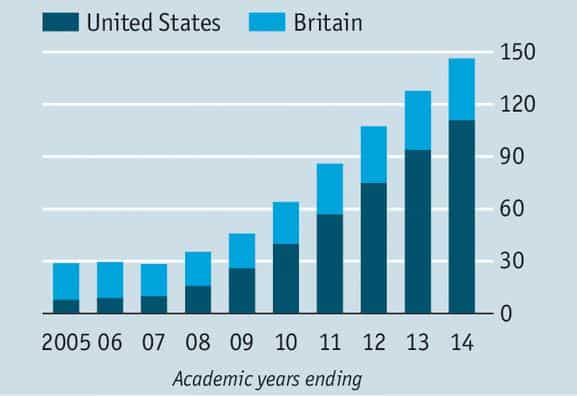

The number of Chinese enrolled in American undergraduate programmes in 2013/14 – at just over 110,000 students – is an astounding 11 times more than in 2006/07, reports The Economist. By contrast, the magazine notes that “the number of Chinese undergraduates in Britain less than doubled over the same period, to 35,000.”

The factors driving growth

There are a host of factors driving Chinese demand for American undergraduate education, some related to the American education landscape and some related to that of China. For example, a key feature of the American higher education system is its sheer range of options, in terms of geography, size of institution, orientation, length of study time required, type of degree, and more. Peggy Blumenthal, a senior IIE counselor and an expert in international education in the US, notes that this expansive system gives Chinese families “a unique opportunity to shop” according to the priorities including price, quality, and school reputation. Shifting demand dynamics in the Chinese marketplace play a role, too. When Chinese students began to move to foreign universities in greater numbers around the turn of the century, the overwhelming factor in their decision-making process was prestige - that is, education as luxury brand. This remains true for many students and families but gradually, a wider set of options is being considered beyond Harvard, Oxford, and other elite institutions. The Economist cites the example of Atlanta’s Georgia Tech to illustrate the diversification of Chinese students' choices over the last couple of years: “Millions of Chinese have dreamed of attending Harvard University. ‘Harvard Girl,’ a how-to manual published in 2000 by the parents of one successful applicant, was a national bestseller. Georgia Institute of Technology, a prestigious university in Atlanta, has enjoyed less name-recognition. Yet this is fast changing: The number of Chinese applicants to Georgia Tech has surged, from 33 in 2007 to 2,309 last year. Some applicants are from the best schools in China, and all are ready to pay around US$44,000 (for yearly fees and housing costs) - the equivalent of nearly ten times the average annual disposable income of urban households.” The magazine summarises:

“The ambitions of Chinese students are shifting: no longer are they attracted just by the glittering names. Pursuit of education abroad is becoming an end in itself.”

And that pursuit is becoming more attainable for greater numbers of Chinese, as the country’s middle class expands and students go abroad at earlier ages. Chinese families increasingly send their high school-aged students to the US so they can have a better chance of being accepted to a prestigious undergraduate programme at an American university. As we reported recently, more than 70,000 international students studied in American high schools in 2013, dwarfing numbers in the UK (25,912), Canada (23,757), and Australia (16,693). For those families with students studying in Chinese high schools, the decision to send their children to the US for undergraduate degrees is often due to one or more of the following factors:

- Few places available at high-quality Chinese undergraduate institutions, despite an increase in the overall number of places across the system;

- Desire to see students avoid the stress of studying for the gaokao entrance examination;

- The great range of high-quality programmes available in the US.

A different trend for graduate studies

The story, meanwhile, is quite different when it comes to Chinese enrolment in US graduate programmes. According to the Council of Graduate Schools (CGS), there was no increase in offers to prospective Chinese students in 2014 compared to 2013 – the first time this had happened since 2006. In fact, admission offers to Chinese students dropped 1% compared to 2013; contrast this to 2012, when offers to Chinese students jumped by 20% year-over-year. This is a major turnaround, and is naturally a concern for graduate schools that have relied on growing Chinese enrolment in recent years. As Science Insider magazine points out:

“China is the biggest single source of foreign applicants to US graduate programmes, composing roughly one-third of the total, so any changes in their behaviour could have a potentially huge impact.”

Here again, interrelated US-China dynamics are at play, according to Ms Blumenthal. She says, “China has pumped enormous resources into its graduate education capacity across thousands of universities.” She also notes that many professors teaching at those universities have a Western education: “They are beginning to teach more like we do, publish like we do, and operate their labs like we do.” The impetus for Chinese graduate students to go abroad is diminished, according to this logic. With the expansion of higher quality graduate programmes at home, this naturally raises questions for some students as to the likely return on investment of an advanced, foreign degree. Furthermore, many Chinese who do go abroad to study come back to China to look for jobs in a highly competitive marketplace. The Economist explains:

“More than 350,000 Chinese returned from overseas study in 2013, up from just 20,000 ten years earlier. They accounted for almost one-quarter of the 1.4 million who had returned in total since 1978. So great are the numbers that there is a derogatory term for those who are unable to find work: hai dai, which means seaweed but also sounds like “[returning from] abroad and waiting.”

Beyond China

China remains the leading source of international students in the US, and has clearly driven much of the recent growth of international enrolment in America. Nevertheless, the shifting patterns of Chinese enrolment in recent years also underscores the importance of diversifying markets. According to IIE, in 2013/14, 42% of the 886,000 international students at American universities were Chinese and Indian, with Chinese students making up almost three-quarters of that proportion. And what of the rest? The 58% who are neither Chinese nor Indian? The IIE’s press release accompanying the most recent Open Doors data includes significant increases from two other countries:

“There are five times as many Chinese students on US campuses as were reported in Open Doors 2000; almost two and a half times as many Indian students; seven and a half times as many Vietnamese students; and more than ten times as many Saudi students.”

Scholarship programmes are to be thanked for some of the most notable gains in US international student enrolments: the three fastest-growing source countries – Kuwait, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia – were all fuelled in part by large-scale scholarship programmes for study abroad. But there will be other factors driving potential growth in the future including population size (and college-age populations in particular), income growth, labour market demand, and the supply and quality of higher education at home. Even as China and India continue to drive overall mobility patterns worldwide, other markets such as Indonesia, Vietnam, and Nigeria (among other key emerging economies) arguably represent some of the best prospects for the next wave of growth and diversification in international education.