Report calls for a more diverse foreign student enrolment in the UK

- A UK commission is recommending a sharper focus on data-driven insights to guide the next International Education Strategy for the United Kingdom

- The UK’s international enrolment growth should not obscure real vulnerabilities in the resilience of the sector, says the “International Education Strategy 2.0” report

- Weaknesses include lack of diversity in student source markets for the UK and an increasing concentration of international enrolments in one-year master’s programmes

The International Higher Education Commission, supported by Oxford International Education Group, has released a bold report presenting data and context about international education delivered by UK providers. The goal of the “International Education Strategy 2.0” interim report is to guide a revision of the UK’s 2019 International Education Strategy and a rethinking of the “one-off” model of such national strategies.

In a foreword to the report, the Commission’s Chair, the Rt Hon Chris Skidmore, MP, notes that there is an urgency to developing an optimal approach to the UK’s next International Education Strategy:

“There are increasing questions about where [the 2019 International Education Strategy] strategy takes us, the consequences of it for the sector and stakeholders, and speculation that future policy announcements may be made on international student visas, in the context of changed geopolitics since 2019, that are at variance with the vital role that UK HE plays socially and economically.”

Mr Skidmore notes that the information gathered for the report “shows unequivocally that this is not a time for complacency; current buoyant international student numbers are largely the result of a particular set of circumstances and unlikely to be sustainable in the long term.”

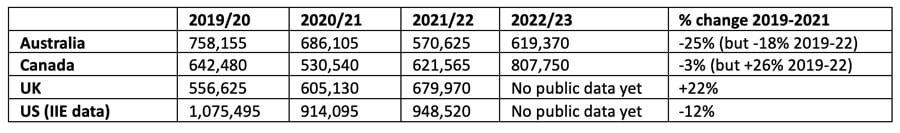

In 2020/21, international enrolments in the UK exceeded the target of 600,000 by 2030 set for them in the International Education Strategy by a full 10 years. The UK and Canada have been the fastest-growing of the major study abroad destinations over the past few years.

Mr Skidmore references several threats to the resiliency of the UK’s international education sector, including:

- Shifting sending markets (i.e., fewer from the EU and more from non-European countries);

- Significant loss of diversity in sending markets;

- Greater reliance on India and a less predictable Chinese market;

- A disrupted “research talent pipeline” (undergraduate and postgraduate enrolments are declining);

- The increasing popularity of one-year master’s programmes that carry with them higher overseas recruitment costs;

- Increasing non-completion rates among students;

- Rising costs of accommodation;

- Lack of consistent data and data collection systems to inform decision-making around international student recruitment.

Importantly, Mr Skidmore asserts: “Underlying all this, key to the ability to establish a coherent and compelling International Education Strategy 2.0, is the need for better data. We should not be reliant on one-off reports, as welcome as they are, to define the economic value of higher education to the country.”

Better data, he adds, would help to make a clearer case for the vital role of international students to the entire higher education infrastructure in the UK – a system that would be in perilous shape should international enrolments decline precipitously.

Myth-busting

The report makes for fascinating reading, and it begins by laying out a set of “assumptions” that “abound across the media, the sector and the government” about international education in the UK. These include assumptions that other markets such as Nigeria will offset enrolment losses from the EU and China and that the UK’s record-breaking international enrolments in 2021/22 mean its brand is strong and that it is back as a leader in the competition for overseas students.

Those assumptions, attests the report, “are misunderstandings at best, and myths at worst.”

Post-study work rights track with enrolment trends

The report tracks international enrolments in the UK over time; its data shows stagnant growth between 2012 and 2019. Not coincidentally, Theresa May’s government instituted a strict post-study work policy (PSW) in 2012 whereby international students had to leave the UK four months after graduation (down from two years previously). The policy was reversed in 2019, and since 2021:

- International graduates have once again been able to work in the UK for two years (three for doctoral/PhD students);

- International enrolments began to increase again after the period of stagnancy.

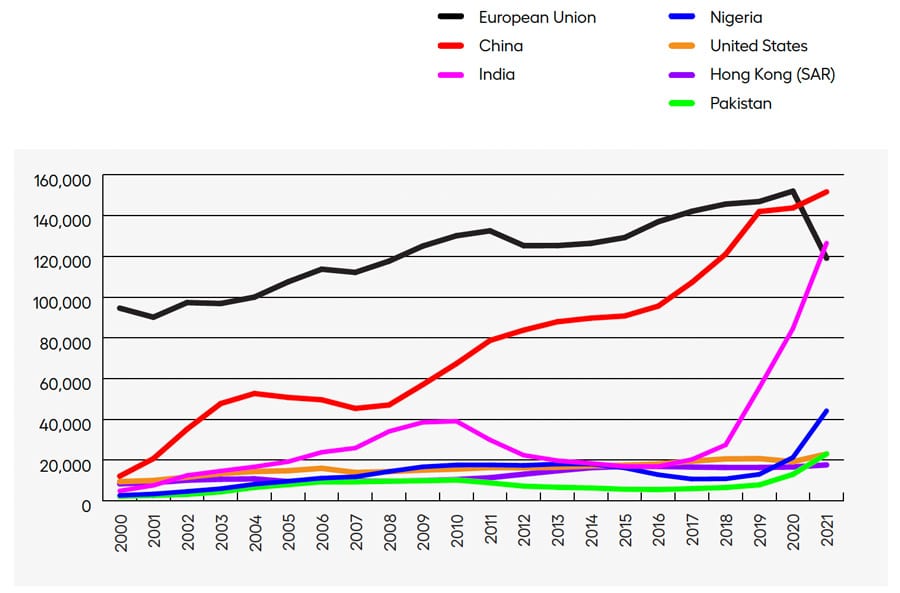

The report notes that “the climb out of the period of stagnation and no growth … mainly impacted student demand from price-sensitive countries.” The following chart shows the sharply increased demand prompted by the restored PSW among Indian, Pakistani, and Nigerian students.

International enrolments much less diverse than in the past

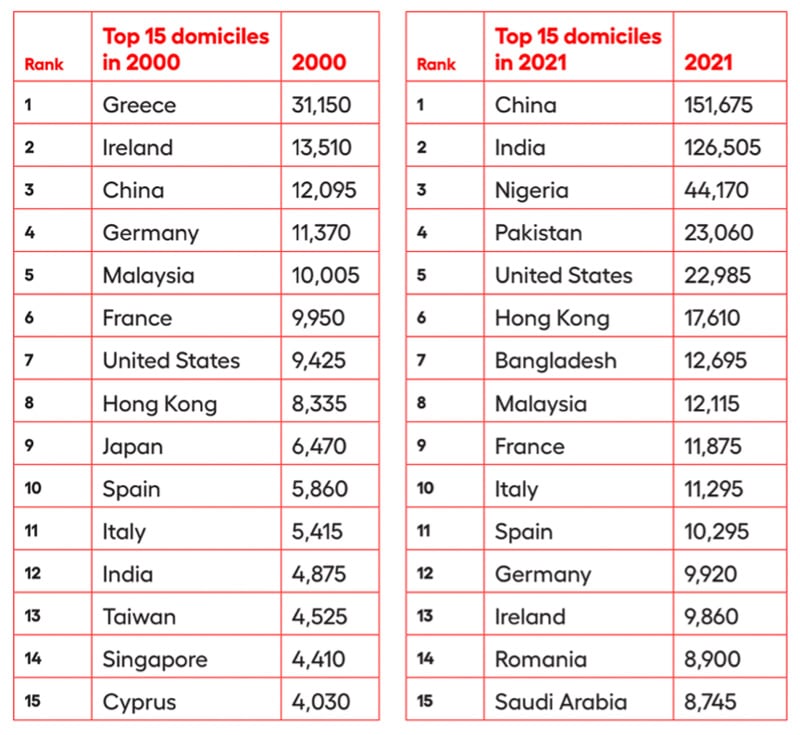

In 2000, Greece and Ireland were the top two sending markets for the UK, accounting for 21% of all international enrolments. In 2021, the situation changed dramatically. The following table shows that not only do the top 15 sending markets look very different, but the top two countries, China and India, compose 41% of all international enrolments.

Higher recruitment costs for one-year master's

Most of the international enrolment growth at UK universities over the past two years has stemmed from non-EU students coming for one-year master’s degrees. Undergraduate programmes are under more pressure as their enrolments have fallen, and there are also costs associated with the popularity of one-year master’s:

“There are substantially increased costs of recruitment associated with the significantly shorter cycle of education – most master’s students need to be recruited annually, whereas the typical first-degree programme is three years. Master’s entrants now account for over two-thirds of the overall student population (68 per cent).”

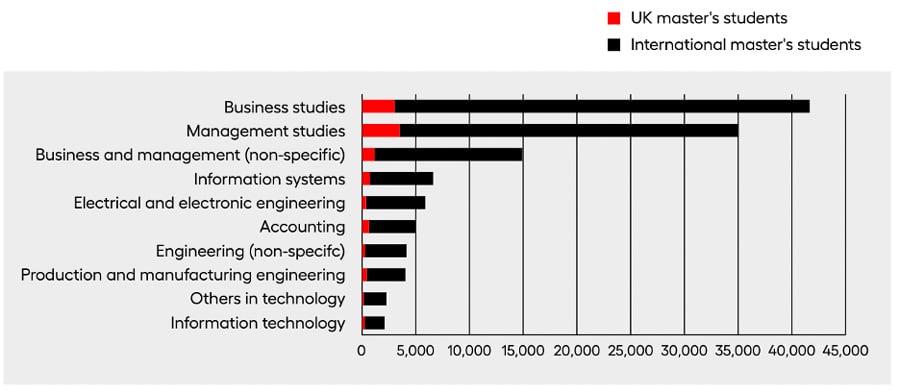

Programmes at risk if enrolments fall

As the report notes, “international students do not displace home students.” If international enrolments fall, domestic students will not take their place – and this has serious implications for many programmes. The following chart shows how heavily reliant some master’s programmes are on international enrolments. What’s more, Indian students make up a massive proportion of students in those programmes. Should the Indian source market decline for whatever reason, the impact would be significant and make it difficult for many programmes to keep operating.

The report concludes that “Without urgent actions to diversify markets and ensure a more balanced distribution of international students across programmes of study, the UK HE sector is potentially in an extremely vulnerable position.”

A new policy announced last month by the Home Office and Department of Education adds urgency to the report’s recommendations. Beginning in 2024, most international students will no longer be permitted to bring dependants with them to the UK while they study. The ban includes master’s students, who currently compose almost 7 in 10 international students in the UK.

This policy strengthens the assertion of Universities UK International (UUKi) and Studyportals that the UK needs to increase its recruitment of EU students. They conducted a 2022 study that found that, between 2020 and 2021, there was:

- A 37% decrease in the number of EU undergraduate applications to UK universities;

- A 47% drop in the number of EU students accepted to UK universities (linked to fewer EU students applying in the first place).

The report noted that:

“[Recent enrolment] growth has been largely driven by historically dynamic markets [i.e., non-EU countries] and we cannot be certain that growth from these markets will be sustained … The EU should form a key part of a diverse recruitment portfolio for UK institutions … once stabilised, European student recruitment flows may be less susceptible to short-term shocks than other sending regions.”

For additional background, please see: