A big-picture view of international student mobility for secondary studies

- International K-12 can take a variety of forms, including the large numbers of students who go abroad to continue their studies, especially at the secondary level

- The Big Four destinations – the US, UK, Australia, and Canada – account for a significant share of this market segment and we explore the dynamics of each leading destination in this special feature

International education takes shape in a number of different ways across the K-12 sector. There is the burgeoning international school sector, for example, where privately owned and operated schools deliver foreign curriculum in students’ home countries. As of 2024, nearly seven million students are enrolled in more than 14,000 such schools worldwide.

The online learning segment for K-12 is also growing quickly, with several established and new entrants in the space serving a growing student population. Our focus today, however, is on internationally mobile K-12 students who travel abroad to pursue their studies. There are many well-established destinations for such students in Europe and elsewhere, but we will limit our scope today to K-12 student enrolments in the so-called Big Four study destinations: the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

Those destinations collectively account for hundreds of thousands of international K-12 students. But the sector’s significance goes beyond that: secondary schools of all types are increasingly seen as an essential recruitment channel for universities and colleges as well.

For post-secondary institutions across the Big Four destinations, international secondary school graduates:

- Are receiving instruction in English and according to a curriculum suited for smooth entry into degree studies in their host country.

- Have gained familiarity with the culture in their host country and understand what it takes to get into a good university in their host country. In fact, many have chosen to go abroad for K-12 education precisely for a better chance of being admitted to a prestigious foreign university in the same country where they are enrolled in school.

- Are living in the host country – making recruitment more affordable and less complicated than recruiting overseas. They graduate with the same credentials as domestic students do, and so their applications are easier to evaluate.

- Come from some of the top target countries for colleges and universities working towards greater diversification (e.g., China, South Korea, and Vietnam).

In the following sections, we’ll look at the dynamics of the K-12 sectors in Australia, Canada, the UK, and US. Across those destinations, K-12 numbers continue to recover following the pandemic. But that recovery is tempered by global market factors including expanding intra-regional mobility in Asia, tougher immigration rules in leading host countries, the growing popularity of alternative destinations outside the Big Four, and the expansion of international K-12 schools around the world.

Australia

International students in Australian schools accounted for just under 2% (19,095) of the total number of foreign students in Australian onshore education in 2024. This is a decrease of 23% since 2019. Of international secondary students, just over a quarter are enrolled in Australian independent (private) schools, mostly at the secondary level (78%). The independent subsector has taken longer to recover than government-funded schools.

In both government and independent schools, China is the largest source country, accounting for 30% of enrolments in 2023. Four other countries composed another 40% of the total: Vietnam, Hong Kong, South Korea, and Germany.

As you can see in the following chart, the schools sector and the non-award sector have had the most challenging time recovering enrolments since the pandemic. English-language teaching (ELICOS) is also off its pre-pandemic level of business, and it was the only sector to experience a decline between 2023 and 2024.

Along with the dent the prolonged Australian pandemic border closure put into educators’ ability to recruit overseas, The Koala News’ Heidi Reid notes that the increasing number of K-12 international schools around the world is a major issue for Australian onshore K-12 schools’ foreign enrolments:

“For the Australian school sector, [the expansion of international schools] simply decreases the pool. As students can study in English in their home country with an international curriculum and native-speaking teachers, they no longer need to go overseas to find this opportunity. This means that Australian schools that will do well will be the ones that provide a uniquely Australian or quality offering and not just a high school education in English.”

Ms Reid also notes that international schools in other countries – which are predominantly British – are not yet a major pipeline into Australian universities because the parents of students are aiming for their children to attend Ivy League or Oxbridge schools.

She recommends that Australian high schools provide more multilingual options, offer the International Baccalaureate (IB) curriculum more, and forge more partnerships with international schools around the world.

Canada

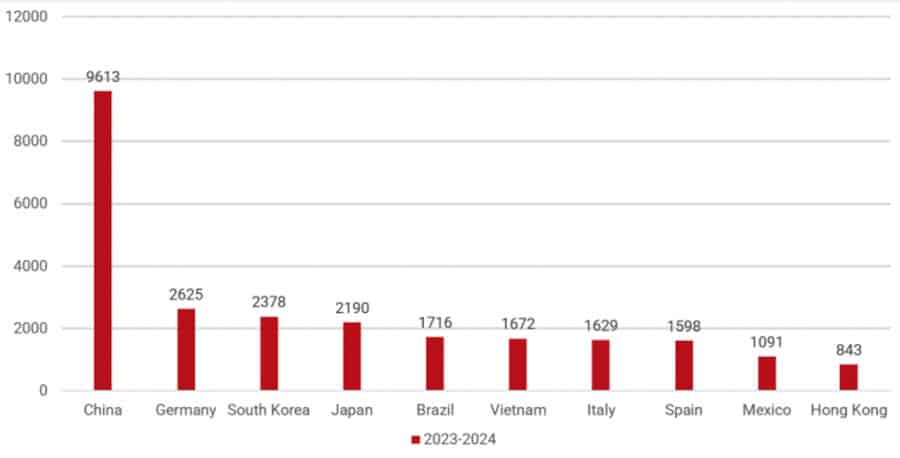

In Canada, according to the Canadian Association of Public Schools – International (CAPS-I) there were 29,580 fee-paying long-term students on study permits for public high schools in 2023/24, and another 4,500 were enrolled for short programmes of less than 4 months (for which students do not need a study permit). This represented about a 2% increase over the previous year.

Growth slowed for students in long-term programmes – those enrolments had grown by 15% in 2022/23. Overall, enrolments in both long and short-term programmes are about 80% of what they were pre-pandemic.

The top five markets are:

• China (+35% year-over-year)

• Germany (-20%)

• South Korea (-17%)

• Japan (+8%)

• Brazil (+20%)

Japan’s increase is notable, as long-term enrolments are now at their highest level in the past decade of data collection. Japan is also the largest source of short-term enrolments.

Several other markets in the Top 10 declined: Italy (-26%), Spain (-17%), and Hong Kong (-19%).

In Canada, major challenges for the sector include rising immigration levels (which are placing greater demands on the domestic education system) and less homestay accommodation than before the pandemic. Global Affairs Canada reports:

“With the additional demand on schools due to the influx of newcomers, there are increasingly less spaces available to international students. This has particularly impacted schools located in larger urban areas.”

Regarding homestays, the pandemic saw Canadian families repurpose their homes to accommodate for offices and returning older children, and lack of homestays remains an issue.

In addition, Global Affairs notes that Canadian schools don’t engage enough with Canadian offshore schools, of which there are 126 in over 20 countries: “These institutions abroad could be valuable partners for student exchanges and short-term enrolments.”

United Kingdom

In the UK, private K-12 schools are anticipating a drop in international student numbers due to the government’s recent decision to make students pay a 20% value-added tax (VAT) on fees and to funnel that money into state schools. The Independent School Council (ISC) says there was a 2.7% decline in new students in 2024 compared to 2023, and notes that “the spectre of VAT is looming large in parents’ minds.” On top of that, inflation has been a compounding issue for private schools.

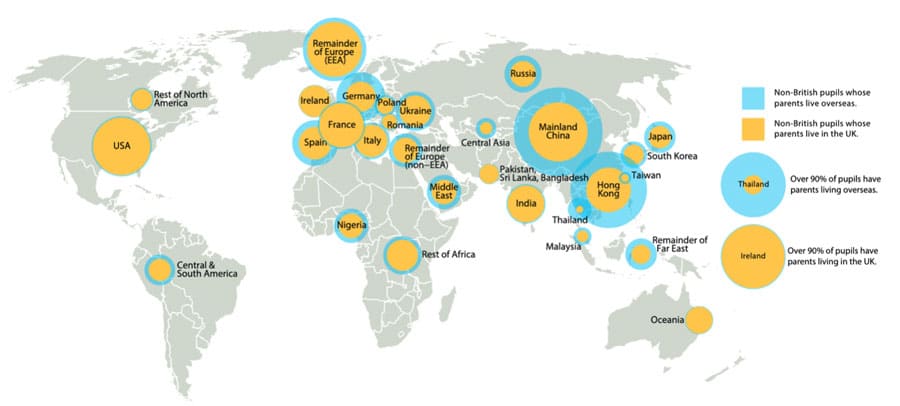

A total of 62,800 non-British students were enrolled in ISC schools in 2024, accounting for 11% of all students in those schools. Close to 27,000 have parents who live overseas – and tend to be “boarders” as a result at the secondary level – and 36,500 have at least one parent with them in the UK. Over 2,000 Ukrainian students are in ISC schools, and 37% of them are in the UK without their parents.

The top source of students whose parents are overseas is China (5,825, and an increase of nearly a quarter after three years of decline), while the top two regions for students whose parents are with them are Europe and the US. ISC notes as well that:

“The number of pupils from both Hong Kong and Mainland China in this [second] category continues to grow. Hong Kong pupil numbers have increased 10% to 2,602 and pupil numbers from China have increased 13% to 4,551.”

British ISC schools may be pressured at home, but many of them find relief in the large numbers of international students they enrol in their offshore campuses. More than 93,250 students are enrolled in 129 campuses overseas, up from 71,660 in 2023.

United States

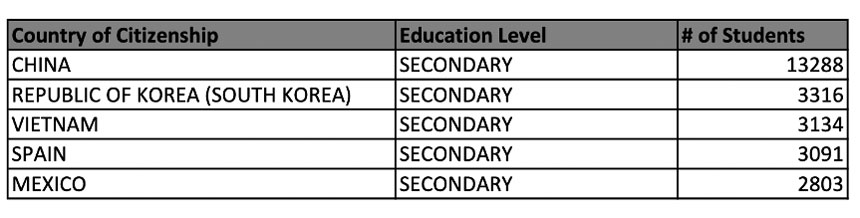

There were 54,560 international K-12 students enrolled in the US in 2023, and most students enrolled in a full academic school year are on F-1 Visas. China is the top market (13,290 in 2023 versus 12,815 in 2022), followed by Korea (3,315 and down from 3,580 in 2022), Spain (3,095 and down slightly from 3,140 in 2022), Vietnam (3,135 and up from 2,880 in 2022), and Mexico (2,805 and stable).

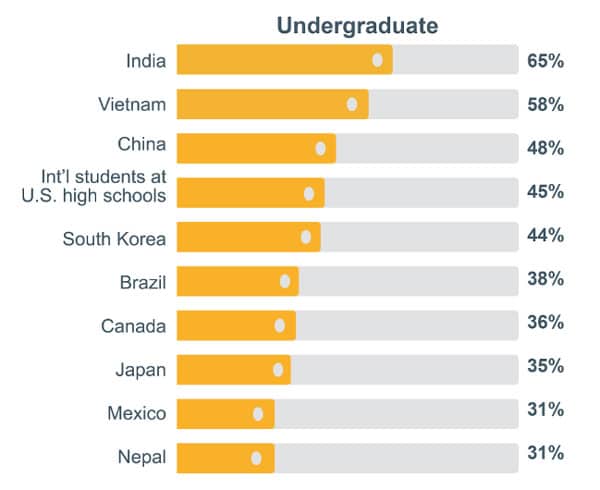

Responding to the Institute of International Education’s (IIE) Fall 2024 Snapshot survey, 45% of undergraduate recruiters said they were prioritising recruitment of international students at US high schools. Again, this underlines the importance of the secondary school sector for higher education recruiters in the Big Four.

For additional background, please see:

- Attend ICEF Secondary Education, a specialist event aimed at recruiting students of secondary education age from around the world.

- “International schools an increasingly important recruitment channel for higher education”