Signs point to cooling demand for UK higher education in non-EU markets

- Demand for study abroad in the UK appears to be falling in key non-EU markets

- Real-time data indicates a declining volume of deposits, confirmations of acceptance, and visa issuances for the January 2024 intake from the key markets of India and Nigeria

- Indians and Nigerians are particularly drawn to one-year master’s programmes, and they have had months to digest the news that as of January 2024, new international students in those programmes cannot bring their dependants with them to the UK

- Some UK master’s programmes – including those focusing on business, management, and engineering – are heavily reliant on international student tuition for their revenues

- Nearly half (44%) of business schools in the UK missed their non-EU recruitment targets this year

Universities in the UK may be facing a challenging year ahead as new data indicates that visas issued to international students for the January 2024 intake have fallen dramatically compared with January 2023.

Real-time data collected on the Enroly Data Insights platform, representing a cross-section of UK universities and based on 58,000 students, found that in these last days of visa processing for the January 2024 intake of international students:

- Overall deposit payments are down by 52% compared with January 2023;

- Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS) issuance is down by 64%;

- Visa issuance is down by 71%.

According to Enroly, more than a quarter of international students come to the UK via its platform.

Driving the steep decline are fall-offs from the key student markets of Nigeria and India. Enroly elaborates:

“The falls are partly driven by a collapse in the Nigerian market, where deposits and CAS/visa issued are down by 74% and 76% respectively. There are indications there will also be large falls in students from the UK’s largest market, India, with deposits down 52% and CAS/visa issued down by 66%.”

Separate data from the Home Office found that visa issuances were flat (0.5%) for the first three quarters of 2023, compared with 33% growth in the same period in 2022. The Enroly data suggests that the stagnant growth is deteriorating to negative growth.

Jamie Arrowsmith, Director of Universities UK International, said that the trend is clearly worrisome:

“The [Enroly] data presented today suggests that an extremely challenging period lies ahead for international student recruitment in the UK. After very strong growth in recent years, numbers are being impacted by a range of global factors. These include competition from overseas – with the USA and Australia reporting strong growth after the end of pandemic restrictions –visa policy changes, here in the UK, and very difficult economic conditions in a number of countries, including Nigeria.

The competitiveness of the UK as a study destination is being significantly tested. It is vital that the UK remains open and attractive to international students, and that government takes steps to reassure prospective students that they remain welcome in the UK, that our universities remain among the very best places in the world to realise their ambitions, and that they can have confidence that the post-study work opportunities provided by the Graduate route are here to stay.”

A link to immigration policy?

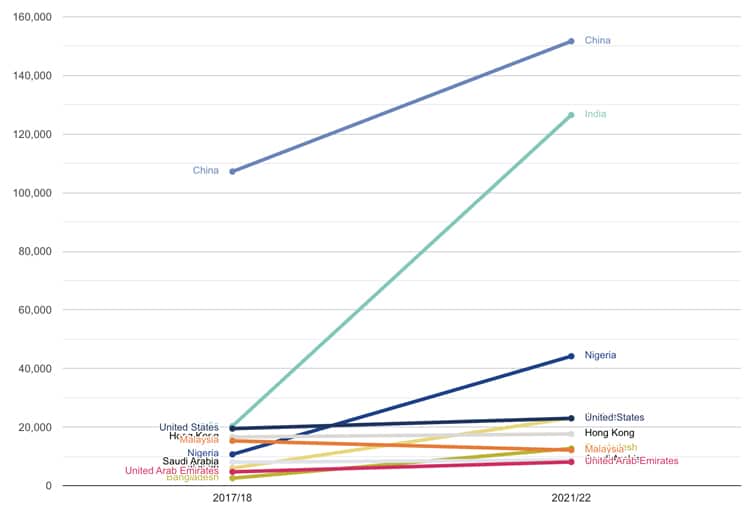

India and Nigeria are the second and third largest senders of students to UK universities, and the following chart indicates the importance of these markets in recent years. The one-year master’s option is a major factor behind the increased popularity of the UK among Indian and Nigerian students. For example, in 2021/22, almost three-quarters (73%) of Indian students in UK education were enrolled in one-year master’s courses.

In May 2023, then-Home Secretary Suella Braverman announced that in January 2024, international students (other than those in postgraduate research courses) would no longer be permitted to bring their dependants with them to the UK. Of particular relevance to Indian, Nigerian, and other non-EU students, those coming for the one-year masters were not exempted from the ban. Ms Braverman called it “the single biggest tightening measure [on migration] a government has ever done.”

Less than 10% of non-EU students are research postgraduates, meaning that less than 10% of non-EU students coming to the UK will be able to bring their family as of January 2024.

Ms Braverman’s office would almost certainly have been aware that the dependants ban might affect Indian and Nigerian student demand for study in the UK. In the year ending March 2023, almost three-quarters (73%) of visas issued to dependants of international students were issued to Indians and Nigerians.

After Ms Braverman’s announcement, prolific tweeter and Nigerian education consultant Dr Dípò Awójídé (@OgbeniDipo) posted on X (Twitter): “Students with families from Nigeria will most likely apply to go study in Canada, Germany, France, Finland or Australia from next year.” Dr Awójídé has over a million followers on the platform.

The new dependants policy may also affect demand from Pakistan (the UK’s #4 non-EU market) and Bangladesh (#7), as these countries are also large contributors of dependants to the UK. Home Office data for the first three quarters of 2023 showed 26% growth in visa issuances to Pakistani students but this “was much slower than last year when visa issuances more than doubled.” Visa issuances to Bangladeshi students fell by 36% for the first three quarters of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022.

Master’s programmes may be badly affected

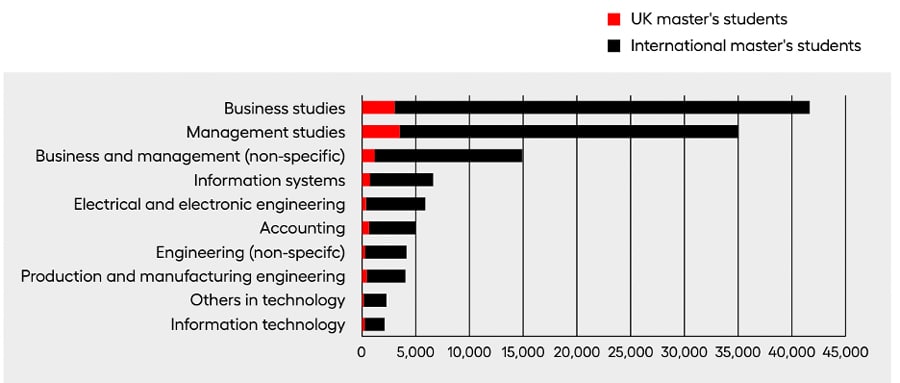

Overall, 6 in 10 of all international students in postgraduate programmes in the UK are from non-EU countries. The proportion of non-EU students in undergraduate courses is also more than twice that of EU students.

Dr Janet Ilieva, founder and director of the Education Insight consultancy, told University World News in July 2023:

“Over 90% of the full-time student population studying engineering and technology at the masters level is from outside the UK. These courses would not be viable if it were not for international students and the same is true for business studies.”

In June 2023, the International Higher Education Commission, supported by Oxford International Education Group, released a prescient report arguing that the UK needed to re-prioritise recruitment and renew a focus on EU markets if only as a risk management strategy.

The Commission’s Chair, the Rt Hon Chris Skidmore, MP, noted that the data collected for the report “shows unequivocally … that current buoyant international student numbers are largely the result of a particular set of circumstances and unlikely to be sustainable in the long term.”

The International Education Strategy: 2.0 report noted that if international enrolments were to fall, domestic students would not take their place – with serious implications for many programmes.

The 2023 Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) Annual Membership Survey found that when reporting on performance against non-EU recruitment targets for the 2023/24 academic year, 44% of members said that they fell short of their recruitment goals (22% reported being "significantly below" their target enrolment). The survey report noted:

"There is significant variation in the results by level of study for non-EU international enrolments, as at undergraduate level nearly half of the schools either significantly or moderately exceeded target compared to one-third of schools at postgraduate level. At postgraduate level nearly 50% of schools reported recruitment that was either significantly or moderately below target for non-EU international students, compared to 21% at undergraduate level."

The vast majority of respondents to the CABS survey said that they expected to see negative impacts on non-EU enrolment arising from the policy largely banning dependants. Enrolments in MBA programmes were expected to be the most affected “as MBA students tend to be older and often wish to bring their family with them.” Members also felt that business schools in competitor countries such as Australia and Canada are already benefitting from the UK’s decision to ban visas for dependents of students.

Other factors at play

The new dependants policy is one likely reason for dampened Nigerian demand; the other is that the Nigerian currency, the naira, has plummeted throughout 2023, reaching a record low earlier this month.

This has put many Nigerian students abroad in financial distress as it costs much more to access foreign exchange. This summer, students interviewed by University World News said that they are resorting to using food banks or walking long distances rather than paying for transportation. Others said that their institution had begun requiring full deposits on tuition amid worries about students’ solvency during the naira devaluation crisis.

Clever, a Nigerian who had gained admission to a UK university, said “she had already gotten a letter of admission before the school wrote her another letter asking for full payment of her tuition.” She said: “I have given up. I don’t know how I can meet up with the school’s demands. The exchange rate has gone up, the money I have is not enough.”

For additional background, please see: