Modelling future international student flows for Australia

- Longer-term forecasts point to continued substantial growth in international student mobility through 2030

- This is true for Australia as well where important questions arise regarding the role of the key Chinese and Indian markets

- There also appears to be a substantial opportunity for Australia to build market share in Africa, a region that is expected to be an important driver of global growth over the rest of this decade

- Those opportunities are tempered by the current policy directions of the Australian government, which may be tending toward curbing current growth rates in foreign enrolment

"How many international students will there be globally by 2030?" asked Jonathan Chew, Head of Insights and Analytics for Navitas.

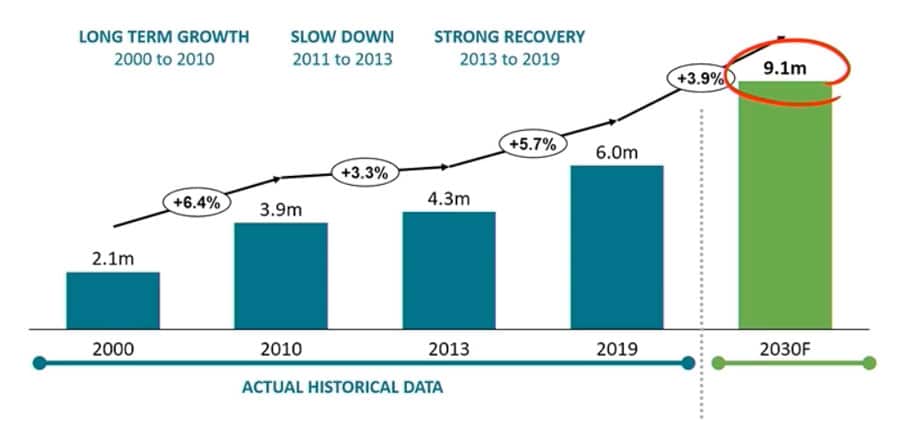

Speaking at the Australian International Education Conference (AIEC) in Adelaide last week, Mr Chew was quick to provide an answer from Navitas' own modelling efforts, which project that the number of students in higher education abroad will grow to 9.1 million by the end of this decade. That is a considerable jump from the roughly 6 million students that were engaged in higher education studies overseas as of 2019, but it is also consistent with other serious forecasting models in the sector.

Within that larger estimate, Mr Chew identified Africa in particular as a "major driver of outbound student flows in the future," with a projected increase of nearly 500,000 additional outbound students from Sub-Saharan Africa by 2030.

Can India become the next China?

Also speaking at the conference, Navitas' Senior Manager, Government Relations Ethan Fogarty raised some important questions about China. The Chinese market fundamentals remain strong and continue to lead forecasters to predict steady growth in outbound student mobility through this decade. But Mr Fogarty acknowledged that there is some uncertainty in that modelling, especially given the downgraded forecasts for economic growth for China coming out of the pandemic, and the knock-on effects of that slower growth, notably the current record-high levels of youth unemployment.

With a more conservative outlook for Chinese growth, what does that mean in terms of the likelihood of India overtaking China as the leading student market for Australia? Mr Fogarty pointed out that Indian outbound has growth considerably faster than previously forecast through 2022, and indeed India has now surpassed China as the leading source market for educators in both the US and Canada.

In terms of overall student numbers, Navitas' analysis indicates that Indian outbound for higher education would need to grow by 10% per year if it is to overtake China globally by 2030. The economic growth forecasts for India would suggest that a further scaling of the Indian economy would be unlikely to drive that level of growth in student movement. However, Mr Fogarty added that it is possible that Indian outbound mobility could continue to grow at faster-than-forecast pace, especially given the very large scale and persistence of broader outbound migration patterns from India.

The African opportunity

Shifting gears to Africa, Mr Fogarty highlighted Nigeria as the major growth driver on the continent, but also noted that Navitas models are projecting growth, to varying degrees, across the region.

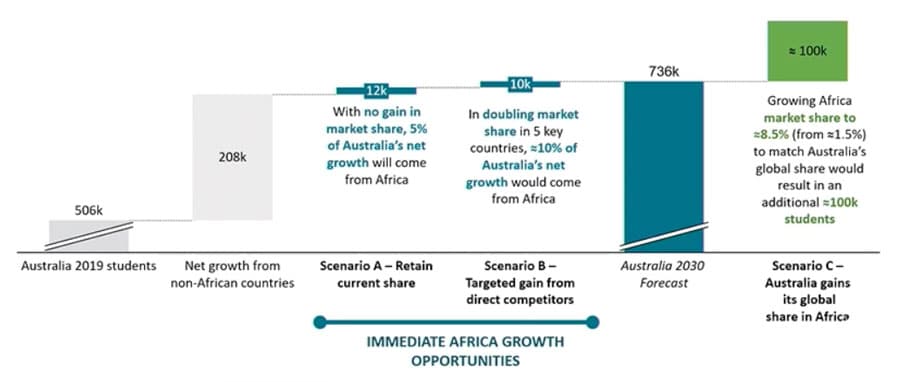

He pointed out as well that Australia's share of the global student market is roughly 8.5%, but that Australia's share across all African countries is only about 1.5%. As we see in the chart below, there is a considerable opportunity gap in that percentage spread. If Australia were to increase its share of African outbound to something closer to its current global share of 8.5%, that would result in as many as 100,000 additional international students in Australia. "Some net growth will naturally come from Africa," he added. "But considerable effort and energy will need to go into realising that [growth] opportunity in the coming years."

The role of public policy

Mr Chew added that if Australia simply continues to grow at its current trajectory, and its global share of the international student market remains at around 8.5%, that that alone will result in an additional 220,000 students in the country by 2030.

That growth trend will in turn push a greater number of Australian universities to a point where roughly half (or even more) of total enrolment comes from international students. "Many universities are certainly pushing past 20%; some hitting 30%, 40%, or even 50% of their total student body being international students," said Mr Chew. "That's going to raise some challenges, some question marks, around is there an upper limit here…We've heard [the government] raise the question some months ago now as to whether there should be an upper limit cap on the ratio [of international students to total enrolment]."

He continued, "When we look at the policy direction, what we hearing loud and clear from government is a much bigger focus on quality, on integrity, on managing the volume and the churn, and on a much greater focus on growing other forms of international education."

Looking ahead, Mr Chew expects that the current policy directions will lead the Australian government to place a greater emphasis on three factors in determining student eligibility and/or selecting students for study in Australia:

- Student motivation ("If you are coming on a student visa, you should be coming here to study.")

- Ability to pay, as evidenced even by recent increases in minimum savings requirements for student visas

- Academic standing – that is, prioritising high-quality students with better prospects for degree completion and career outcomes

What this potentially adds up to, he suggests, is a government orientation to a smaller international education sector in Australia. "This could amount to a slowing of growth," he cautions, "rather than a contraction of the sector."

What that analysis suggests, in other words, is that the current policy direction could result in a curb or cap on growth that would seek to lead the Australian sector, at least in terms of higher education enrolment, to a growth curve below the baseline indicated above – that is, the baseline that would lead to another 200,000+ students if Australia simply maintains its current share of the global student market.

For additional background, please see:

- "Australia’s foreign enrolment surpasses pre-pandemic benchmarks"

- "Australia takes action on fraud in student visa system"

- "Pandemic Event Visa scrapped as Australia continues overhaul of student visa policies"

- "Australia expands regulatory oversight of education agents and announces new integrity measures for VET"

Most Recent

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More