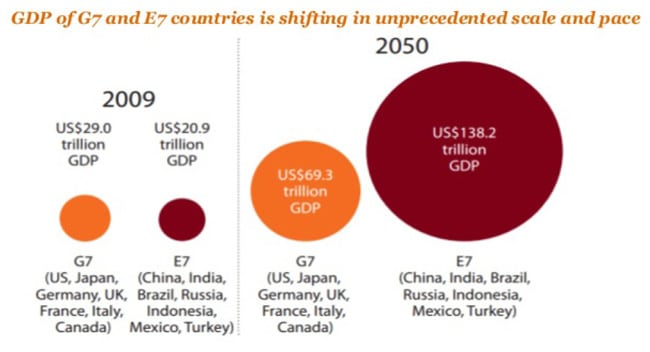

Megatrend: The shift to emerging markets

Economic and population growth are shaking up the global power structure – away from the G7 countries and towards Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

According to PwC projections, China’s economy will unquestionably be larger than America’s by 2028. The economy of India will be the second largest by 2050, Mexico and Indonesia will surpass the UK and France by 2030, and Nigeria and Vietnam will be among the world’s fastest-growing economies over the next three or four decades.

1. More demand, more choices

Millions of international students continue to pursue degrees at established institutions in Western markets. Foreign enrolments in the US alone broke the one million mark in 2015/16. More students than ever are also flocking to Canada, Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand. But notably, America’s market share slipped from 28% in 2001 to 22% in 2016, and foreign enrolments in the UK have not grown since 2012. By contrast, Asian destinations are attracting ever more international students, particularly from within the region. Prestigious American and British universities used to be able to count on their reputations to attract international students, but this is changing. A growing segment of international students – while still looking for high-quality degrees – are now open to alternative destinations that are more affordable and close to home. When such destinations also offer relatively welcoming visa policies and options for international students to work during or after their studies, they become still more attractive when measured against the more restrictive visa and immigration policies of the US and UK. This brings us to the second trend: Asia is solidifying its position as a compelling regional hub for students considering study abroad.

2. Asia reaches out

The governments of Japan, China, Malaysia, Taiwan, and South Korea have been hard at work increasing domestic higher education capacity, and they have set ambitious targets for international enrolments in 2020 and beyond – targets they are on track to meet. Asian institutions are also climbing up world university rankings, such as the Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings and the Shanghai Ranking. Fully one-tenth of the universities on the Times Higher Education 2016–17 Top 100 ranking are Asian, for example. One of the biggest stories of 2016 was that China hosted so many international students (442,773 – an 11.4% increase over 2015) that it now vies with Canada for fourth place as a destination market, behind only the US, UK, and Australia. Even five years ago, China could only have been categorised as a major sending market. Economic power shifts are a major factor in turning students’ attention to Asian destinations: China is a superpower in this respect; India has the fastest growth rate of any major economy; and the ASEAN countries of Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam are responsible for one-third of world trade. The next generation of leading study destinations, then, is already coming into focus. As the centre of economic and political power shifts to Asia, international students – not only from within the region but from the West as well – will increasingly consider Asian institutions for study abroad. Even the highest ranked Western institutions, which traditionally haven’t had to recruit overseas in earnest because of their reputations, will have to compete more strategically and vigorously, starting now. For additional background, please see: