Global survey says English teachers are both enthusiastic and concerned about AI

- A British Council survey of English-language teachers in 118 countries finds that most teachers are already using some kind of AI-powered tool

- Teachers believe AI offers benefits in terms of their instructional capabilities and also students’ ability to learn, but they are also concerned about over-reliance on AI

- Most do not feel they have been provided enough training to incorporate AI into their work

A new British Council study sheds light on English-language teachers’ use of, and attitudes toward, artificial intelligence in their work. Informing the study was a survey of 1,348 English-language teachers from 118 countries, who provided feedback on how they are using AI, what they consider its benefits to be, and what role they believe it will play going forward in English-language instruction and learning. The sample included teachers working at the elementary, secondary, and post-secondary level at various types of institution.

The study, written up in a report called Artificial intelligence and English language teaching: Preparing for the future, set out to find the answers to questions such as:

- What impact will AI have on how our learners gain knowledge and develop skills?

- What impact will it have on how we recruit and train our teachers?

- Will teachers ultimately be replaced by technology?

These are important questions, given that, as UNESCO says, “emerging [AI] technologies present immediate – as well as far-reaching – opportunities, challenges and risks to education systems” and that English-language learning is expected to be the educational niche most likely to be affected and changed by AI.

The British Council says that as a result, “English language teacher education and training must include a focus on AI literacy.” At this stage, they say, there isn’t enough deep engagement with the immense impact that AI will have on the sector, despite some resources such as blogs and how-to guides now available to teachers.

Part of their study involved an extensive review of research focused on the topic, which led to conclusions such as:

- “Teachers need to develop their learners’ AI literacy so that they can understand the limitations and risks of AI and discuss the ethical issues around its use.

- Practitioners should carefully consider how models are chosen, as AI may carry messages about language use and exclude certain groups/varieties of English.

- AI can provide a conversational partner, provide language practice outside class and alleviate learner anxiety about speaking. However, more evidence is needed on whether the gains persist independent of such AI tools.

- Accessible and unambiguous ethics statements for AI in ELT should be developed and committed to, along with clear systems to ensure data privacy.

- Practitioners should be realistic about the current limited capabilities of AI and cautious about the hype.”

Survey insights

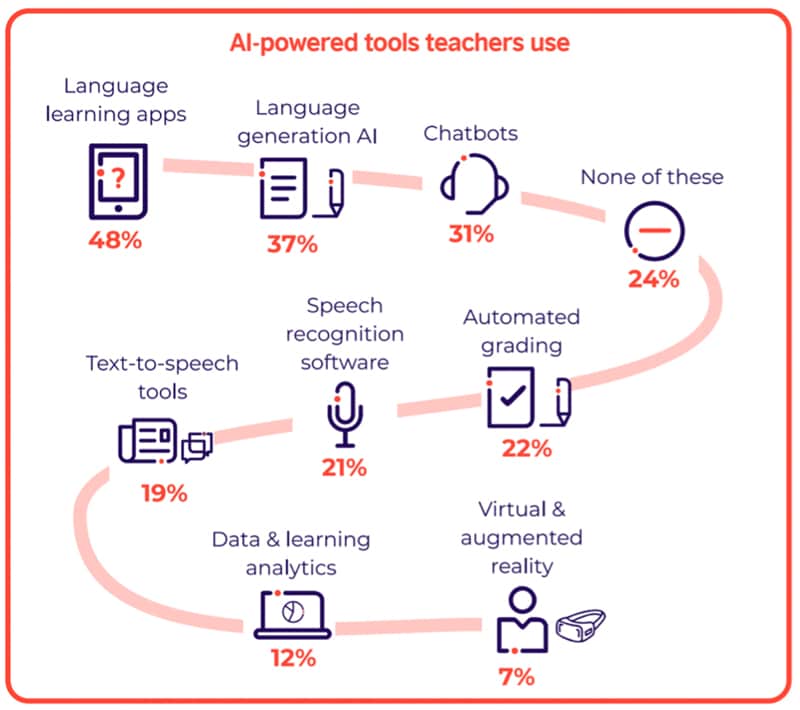

Three-quarters of surveyed teachers already use AI in one form or another, as illustrated in the following chart. The most common tools being used are language learning apps (48%), language generation AI (37%, and chatbots (31%).

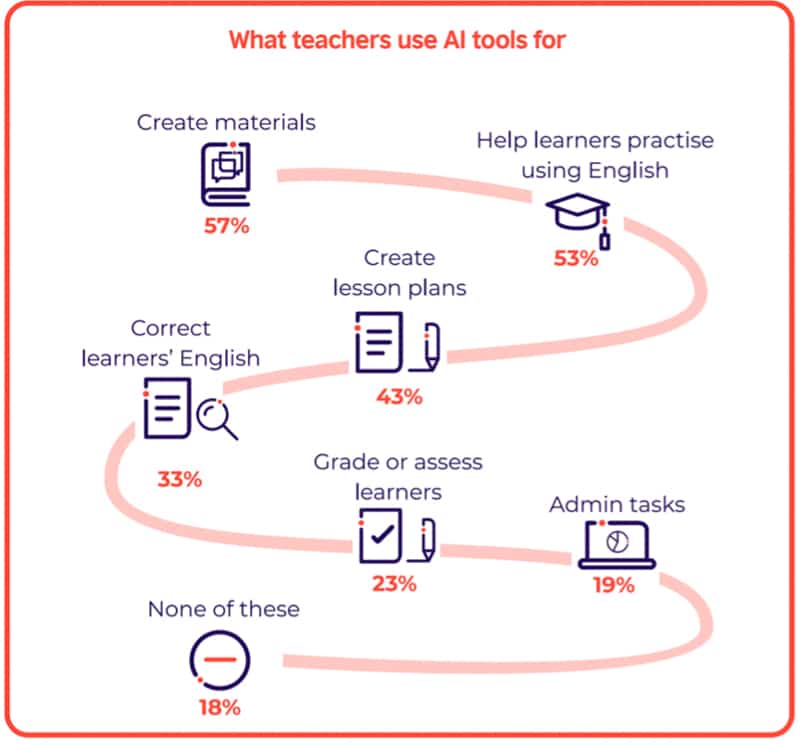

The most common reasons for using AI are to create learning materials (57%), helping learners to practise English (53%), and creating lesson plans (43%).

Teachers were asked if they thought AI could help learners in four related realms of English-language learning (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) and there is broad agreement that it can. More specifically, teachers are most excited about AI offering “innovative tools for learning, real-time editing, the ability to adapt to learners’ levels, and providing engaging reading materials.”

Teachers do see downsides as well, however, including “AI’s lack of human emotions and inability to fully grasp language nuances like humour.” They also expressed concerns about over-

reliance on AI. The report notes:

“Many of the 129 written explanations provided expressed concerns about dependency, noting that learners might ‘misuse’ AI or ‘rely on it more than their natural abilities’. Quotes like ‘What’s the point in learning English when AI can speak for me?’ and ‘Students will rely [too] much on AI, resulting in a lack of confidence’ illustrate the perceived risk of over-reliance.”

Overall, teachers feel that AI-powered tools and content “should complement, rather than

replace, existing methods [of instruction].” The British Council found a “consistent emphasis” across respondents “on the irreplaceability of the unique human touch in teaching, highlighting the emotional, cultural and social facets of ELT.”

Asked directly about whether they believed that by 2035, “AI will be able to teach English without a teacher,” about half (51%) of teachers disagreed compared with 24% who agreed. But, as the British Council points out, 26% remained neutral, indicating significant uncertainty about the potential of AI in this area.

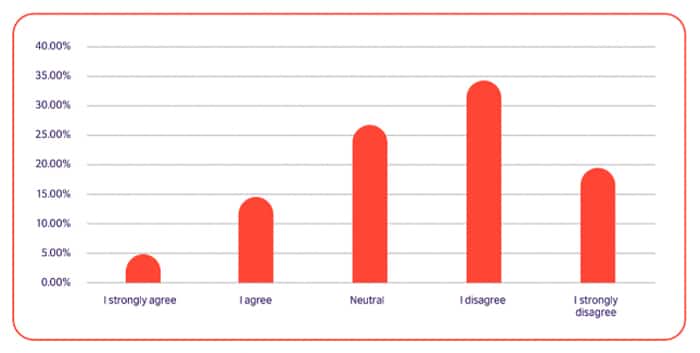

The survey revealed that most teachers do not feel they have received enough training to incorporate AI into their teaching. As shown in the following screen shot.

Final thoughts

In the concluding section of the report, the authors express some skepticism about the potential of AI to fundamentally transform education. They write:

“Steve Jobs famously said, ‘We’re here to put a dent in the universe’, but institutional education remains stubbornly dent-free. Whether new technologies will bring the widespread systemic change that matches the AI hype is an ongoing debate. A reading of the history of educational technology would say otherwise.”

For additional background, please see: