Internationalisation of Chinese education entering a new phase

China’s higher education system continues to expand at a breakneck pace. Enrolment levels and participation rates are all trending sharply upward, and the system continues to grow at the equivalent of roughly one new university per week. UNESCO statistics indicate that gross enrolment ratios (the percentage of the college-aged population enrolled in tertiary education) have spiked over the last five years as well, from about 24% in 2010 to just under 40% as of 2014. This translates into nearly 42,000,000 students in tertiary education programmes in 2014, and compares to an enrolment of roughly 20 million in the US higher education that year. The sheer scale and pace of expansion, however, is hardly the whole story. China has made substantial, targeted investments in the quality of its higher education, most recently through a new initiative called “World Class 2.0” (also referred to as the “Double World Class Project”). Announced in August 2015, the programme aims to strengthen the research performance of China’s nine top-ranked universities, with the goal of having six of those institutions ranked within the world’s top 15 universities by 2030. The continuing development of the Chinese system will no doubt be one of the big stories in higher education over the next decade and more. But the effects of China’s massive investment in education are already being felt across Asia and around the world:

- This year’s Universitas 21 ranking of higher education systems reveals that China is the most-improved nation since 2013, having moved up 12 places in the global ranking table over the past four years.

- In the most recent Times Higher Education BRICS & Emerging Economies Rankings, Chinese universities held the top two spots, half of the top ten, and 39 positions overall in the 200-institution table.

- China is now one of the world’s top study destinations, and attracted nearly 380,000 foreign students in 2014. International enrolment in China increased by 15% between 2012 and 2014, and the country aims to host 500,000 students by 2020.

- The growing strength of Chinese higher education is contributing to a shift in outbound mobility patterns as well. For example, whereas most Chinese students in the US have traditionally pursued graduate studies, the balance has shifted over the last 15 years to the point where now roughly equally numbers of Chinese students are enrolled in undergraduate and postgraduate programmes. This is in part because more Chinese scholars are staying home to do their postgraduate work and research at domestic institutions.

Along with its domestic priorities for economic and social development, it has become increasingly clear that China sees education as a means to expand and exercise its influence abroad. Most recently, this interest is reflected in the rapid expansion of cooperative links between Chinese universities and foreign partners.

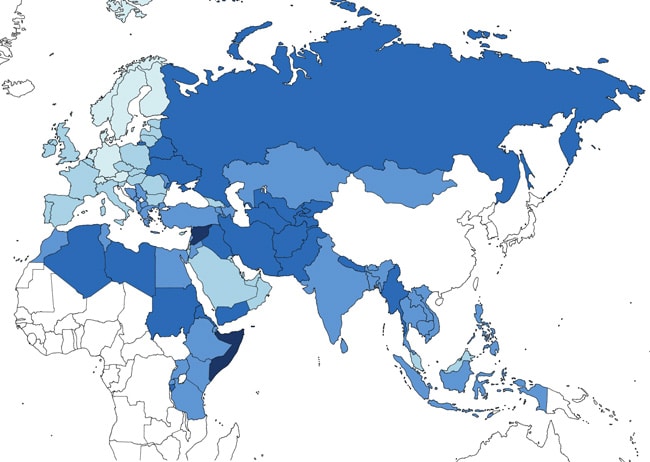

In 2013, the Chinese government announced a massive development and foreign investment framework known as “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR). An invocation of the traditional Silk Road trade routes between Asia and Europe, OBOR aims to leverage China’s massive production and financial capacity through new projects and partnerships throughout Asia, Europe, and Africa.