South Korean student mobility takes a dip

South Korea has traditionally been one of the world’s most robust sending markets, surpassed in numbers of students abroad only by China and India, but recent information suggests that after years of fairly stable numbers, a 2012 dip in South Korean sending may continue into this year and beyond.

More South Koreans are staying home

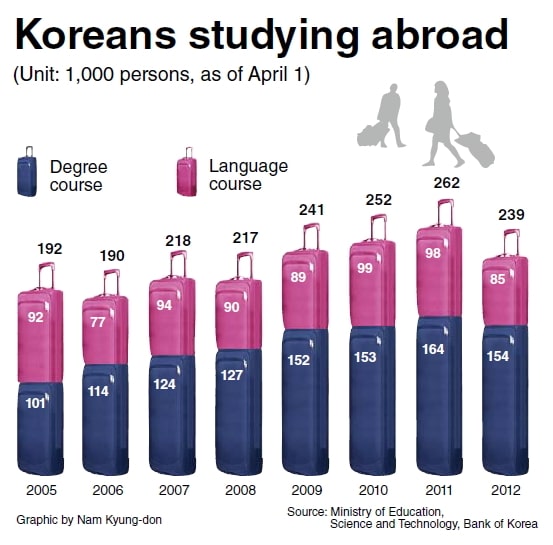

Recent data from the South Korean Ministry of Education and the private education group Etoos reveals that fewer South Korean students are opting for overseas study. The latest Open Doors data confirms this as well, registering 73,351 students in the US from South Korea in 2010/11 compared to 72,295 in 2011/12 – a drop of 1.4%. Although this is not a massive figure, mobility shifts can have a significant effect on countries that recruit heavily from South Korea, such as the US, where they make up almost 10% of the total international student body. South Korea is also a top sender of students to Canada, as well as to regional spots like China and Japan. Reports indicate that this shift is occurring due to a declining birth rate (the number of high-school graduates is expected to drop from 670,000 in 2012 to 410,000 in 2024) and an economy that is losing middle class families. More specifically, the proportion of middle class households in South Korea shrank from 75.4% in 1990 to 67.5% in 2010, according to an August 2013 report by the global consulting firm McKinsey. McKinsey attributes this decline partly to a shrinking number of high-paying jobs with major business conglomerates, a trend that has led to a standstill in middle class income growth. The report also warns that half of all middle class South Korean households now risk falling into poverty. With income growth stalled, international schooling is increasingly unaffordable for middle class families. A report put together by the Bank of Korea showed that approximately 154,000 students were pursuing degrees at overseas universities in 2012, a 6% drop from 2011 (see the graphic below). Oh Jong-un, evaluation director at Etoos, told the Korea Joongang Daily earlier this year,

“It has become much more burdensome for parents to pay for overseas study expenses including school tuition under the current economic conditions.”

Yet despite the economic burden, South Koreans continue to spend a tremendous amount on education. Nearly 75% of South Korean youngsters participate in the private education market, valued at approximately US $17 billion in 2012.

Better opportunities at home?

Still, there’s no doubt that South Korean high school graduates are increasingly exploring the option of attending local universities. Korea Joongang Daily quoted Im Seong-ho of the Korean private education group Edusky, as saying,

“Parents with high school students now think it’s better to go to a domestic university for better job opportunities.”

While the costs of university in South Korea can be high, attending university at home offers college students the chance to develop their personal networks, something deemed in Korean society to be highly important to one’s future prospects. Some observers have also pointed out that a surplus of foreign school graduates in Korea has made them less attractive to employers, creating yet another disincentive for going overseas to study. These mobility shifts are something for universities and agents, particularly those in top receiving countries for South Korean students (Japan, Australia, UK, Canada, Germany, USA, China), to keep an eye on. It’s also a reminder to consider diversification into secondary recruiting markets in order reduce one’s reliance on a small number of key countries. Some markets in the region to consider include Thailand and the Philippines, where reforms are seeing those countries’ K-12 sectors overhauled, and Vietnam, where GDP has tripled in the last decade and the 45% of the population that is under the age of 25 are increasingly looking abroad for schooling opportunities.

Private tutoring market buoyant

That said, even with fewer South Koreans studying abroad, the right recruiting approach can still be effective. Private tutors outnumber teachers in South Korea, which is an indication that families expect a high level of engagement from anyone involved in their child’s education. For instance, tutoring academies routinely send parents text messages when their children arrive for classes. Progress reports either by text or phone are normal. Educators and agents working in South Korea routinely go the extra mile to meet the expectations of parents. Tutoring services are deemed so essential that some tutors have attained the status of rock stars, such as Kim Ki-hoon (who earns US $4 million a year teaching English). This further suggests that South Koreans gravitate toward models of success. Universities might consider promoting successful alumni in their marketing, and utilising elite imaging to appeal to upper class parents, along with a keen focus on what benefits the education provides. Benefits such as social status sometimes even supersede all other motivations for learning. “Some of the national elites who founded the nation itself, they all studied in the States, they all speak English and people kind of internalised this image: If you speak good English you will become an elite in this society,” explains Lee Mun-woo, assistant professor at the department of English language education at Hanyang University.

Changes to Korea’s education system

Meanwhile, with more South Koreans staying home, let’s take a closer look at how their education system is evolving. In the boarding school sector, schools have been granted more autonomy and have been provided subsidies worth up to US $265.8 million. These changes led to an increase in the number of boarding schools to 837 last year - a quantum leap from the 584 that existed in 2008. This level of growth was even enticing enough to attract venerable Western boarding schools such as Canada’s Branksome Hall and Great Britain’s North London Collegiate School. In the tertiary sector, the South Korean government has made moves to address both the quality of higher education and the public’s concerns about its high cost. The government has spent more on scholarships and now restricts yearly increases in tuition to 4.7%, down from 5% in 2012. President Park Geun-hye pledged during his campaign to reduce college tuition by 50%, and the Education Ministry plans to give scholarships to economically disadvantaged students in the bottom 30% income bracket. A development that addresses both cost and access has seen some of South Korea’s leading universities introducing digital versions of their courses. Some examples:

- Korea University is offering 300+ courses via the iTunes Store in areas of study that include humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, Korean studies, and engineering.

- Ewha Womans University offers 10 courses and 150 other supplementary educational programmes in subjects such as art, natural sciences and history.

- Ulsan University plans to offer 15 regular courses and 274 lectures.

- Seoul National University, one of the country’s best, plans to stream free lectures via YouTube.

Korea University expects these online services will boost collaboration with foreign colleges and students: “We are in talks with overseas colleges to co-produce lectures. We also exchange translation services with Japan’s Hokkaido University,” said Lee Hee-kyung, director of their Center for Teaching and Learning.

A flourishing vocational sector

Vocational schools are likewise receiving an overhaul. South Korea’s Ministry of Education has a new policy proposal that will lead to 70 trade schools revamping their curriculum in 2014. The selected schools will offer more hands-on training sessions and follow South Korea’s National Competency Standards, a set of benchmarks that rate worker competence in 800 occupations. The plan will be extended to 100 schools by 2017. It isn’t just the current government that has paid close attention to vocational schools. In 2008, ex-president Lee Myung-bak launched an initiative called “Meister schools” that gave high school students experience working in various trades. There are currently 35 Meister high schools - all funded by the government and major business firms - and the number is expected to surpass 50 this year. In 2009, more than 70% of vocational high school graduates went on to college, a number reflecting the strong belief among South Koreans that university was the best path to good jobs. But last year, that percentage fell to 55% because approximately one third of vocational high school graduates found immediate employment. Conversely, the job market for college graduates is tight. Government data showed a mere 50% full time employment rate for college grads, and according to the Hyundai Research Institute there were more than 3 million unemployed college graduates in the first quarter of 2013, 18.4% of the total. These factors have helped the vocational route gain popularity among young Koreans. Add everything together - economic factors, networking opportunities at home, and expanded in-country schooling options - and young South Koreans have more reasons than ever to attend university at home. Once the 2013/14 admissions results are tallied in Korea’s traditional receiving markets, observers will have a better sense of whether the 2012 decline is a mere blip or a real trend.

Most Recent

-

ICEF Podcast: Engine of growth: The true value and impact of the international education sector Read More

-

Global higher education enrolments expected to grow through 2035, but new challenges must be addressed Read More

-

Canada: A case study of immigration policy impacts on postsecondary institutions and the wider economy Read More