New research on global employment trends for youth paints a severe picture

Youth unemployment has risen by 26.5% between 2008 and 2011, leaving a staggering global population of nearly 75 million people aged 15-24 without a job. While our industry strives to get the right students into the right educational institutes around the world, and to enhance their skills through language learning, apprenticeship or internship experience, others question the value of higher education these days. Some say fewer young people are taking gap years to travel or volunteer abroad due to a pressing need to pay off burgeoning student loans. Others report that people are staying in higher education longer, 'hiding' from a difficult job market and postponing graduation for as long as possible. The problem stretches across the globe from first world countries like the US and UK to developing countries in Africa. One can't help but look at the youth situation in the PIGS nations (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, Spain) and wonder how this generation will evolve - how can we educate today's youth? How can we encourage them to study, work and travel abroad? How can we persuade them to bring their knowledge and new-found cultural understanding back home? And how can they positively contribute to a global economy? The Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) speculates on what students today need to learn and urges governments and universities to work hand-in-hand with industry and businesses, to ensure today's youth can secure employment upon graduation:

"My hope is that schools, universities and training programs will become more responsive to the workforce and societal needs of today, and students will increasingly focus on growing and applying essential 21st century skills and knowledge to real problems and issues, not just learning textbook facts and formulas. This will raise levels of creativity and innovation, and provide better skills, better jobs, better societies, and ultimately better lives."

You talk to today's youth every day. Some fear the future job market and they (or their parents) will do everything in their power to give them a leg-up over the competition to ensure a brighter future. Which degrees offer the best chance of employment upon graduation? Which school is the best match for a student? Which foreign language is the best to learn? How can a work or volunteer experience overseas help today's youth in the future? And ultimately, what happens after the education - what is the real employment picture around the world? ICEF Monitor strives to find answers to these pressing questions, and we turn today to youth employment, to bring you the latest data on where progress has or has not been made, updates on world and regional youth labour market indicators and detailed analyses of medium-term trends in youth population, labour force, employment and unemployment. A new report entitled "Global Employment Trends for Youth 2012" examines the continuing job crisis affecting young people in many parts of the world. By incorporating the most recent labour market information available, it provides updated statistics on global and regional youth unemployment rates and presents International Labour Office (ILO) policy recommendations to curb the current trends.

Key highlights

This year’s report shows that the impacts of the crisis have been disproportionately severe for young people around the world, and that those in developed economies have been especially hard hit. The youth unemployment rate has remained close to the crisis peak in 2009, and medium-term projections suggest little improvement. Particularly worrisome is the increase in those youth who have withdrawn from the workforce, and in those who are neither in education nor in employment.

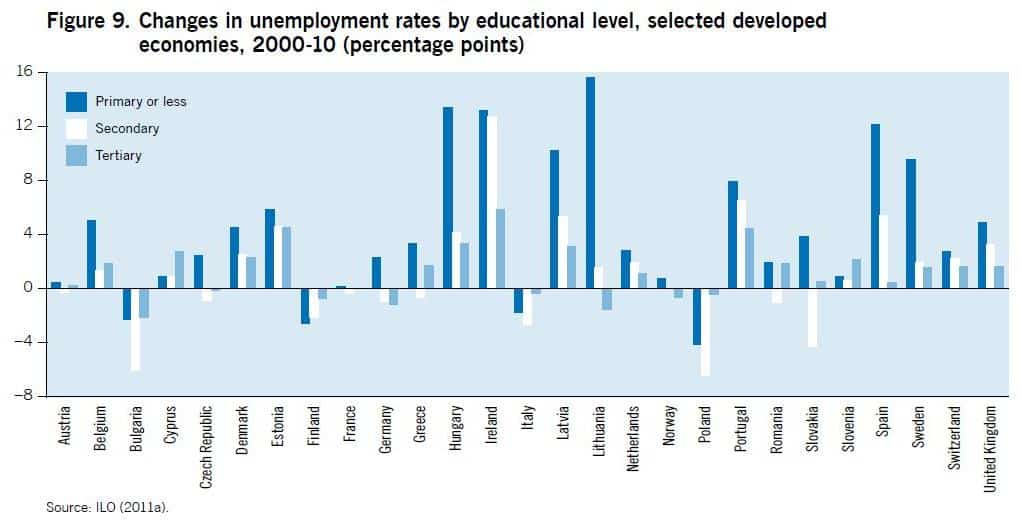

Although education is generally a 'shield' against unemployment, study findings indicate that the graduate unemployed were not spared in the face of the economic crisis. In the sample of developed economies shown below, the unemployment rate of persons with tertiary education rose in 18 countries and declined in eight countries. In two countries, Cyprus and Slovenia, the educated unemployed were the hardest hit, showing the largest increase in the unemployment rate over the period.

Not only more, but better education and training is needed in developing economies

In many Sub-Saharan African countries higher educational attainment does not lead to lower unemployment rates. Similarly, in many Latin American countries, unemployment rates are highest for those with secondary education (e.g. in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile and Mexico) while those with primary and sometimes tertiary education show lower rates. Furthermore, in Pakistan higher educational attainment has been shown to increase the likelihood of unemployment for both adults and youth. These facts notwithstanding, educational attainment has also been positively associated with the likelihood of securing paid employment in the case of adults in this country. These findings suggest that even though more education may not automatically result in more jobs, it allows young people to secure entry into non-vulnerable employment. In other words, the situation that youth in many developing countries are facing is such that education does not guarantee a decent job but such a job is very difficult to secure without education. If historical trends are taken as benchmarks, several Asian countries would be considered to raise educational attainment levels too fast. At the same time, education can serve as a driver of development, by empowering people to develop or adopt new technologies and diversify production structures. Recent ILO research found that countries that have managed to successfully catch up with developed economies, such as the Republic of Korea, typically experienced a transformation of the education system that preceded the transformation of the production structure. In this respect, proper labour market information is necessary to facilitate both the role of education in meeting current labour demand and in facilitating change. The 2012 report offers valuable lessons learned from in-depth regional and gender analysis as well as recommendations on youth employment policies. Ideally, these will shape future developments, as countries continue to prioritise youth in their national recovery policy agendas. The ILO reminds us that youth "are the drivers of economic development in a country, and forgoing this potential is an economic waste. Designing appropriate policies to support their transition to stable employment should therefore be a country’s highest priority." The complete 2012 study can be found here. Source: ILO