Wholesale changes for Japanese education arising from globalisation and demographics

Japan’s education system is on the cusp of significant change as the country’s schools and institutions continue to adapt to sweeping globalisation initiatives and the pressures of a declining school-age population. The outlook is that admissions policy and curriculum - even the makeup of the system itself - all stand to be very different in the near future than they are today. Japan could be fairly characterised as a mature market in terms of study abroad. The number of Japanese students going abroad has declined steadily over the past decade, from a peak of 83,000 in 2004 to 57,501 in 2011. It remains an important source market for many global study destinations, however, and there are indications of an uptick in interest in study abroad among Japanese students. For instance, surveys of Japanese students have measured an increasing interest in overseas study in recent years. Most recently, a 2014 British Council study of 2,000 Japanese university students found that 45% wanted to pursue academic studies in a foreign country, with 79% of those indicating that their primary motivation for doing so would be to improve foreign language skills and to experience another culture. That survey result emerges against a backdrop of expanding globalisation initiatives within Japanese education. Late last year, the government announced the “Top Global University Project,” an ambitious programme to concentrate additional investment in 37 top institutions in order to expand their internationalisation efforts and place more Japanese institutions among the top-ranked universities in the world. “Top Global” builds on a foundation of ambitious internationalisation plans already set out by the Japanese government. These include the Global 30 Project, through which leading Japanese universities offer complete degree programmes in English, and a broader goal to build international enrolment in the country to 300,000 students by 2020. The government has also taken steps to expand support for outbound student mobility and has announced reforms to further internationalise Japanese curricula through the expansion of English language instruction in primary grades as well as a proposed redesign of university entrance exams. Taken together, these initiatives are clearly aimed at boosting the international competitiveness of Japanese institutions and their graduates. They reflect as well a national commitment to education as a source of innovation and economic development.

Challenges at home

Even as it increasingly opens up to the world, Japanese education is facing a number of important challenges at home. The country’s postsecondary system expanded quickly over the past two decades, particularly through the establishment of new private universities, and it now has more university capacity than it needs. “For decades, Japanese universities had many more applicants than openings,” says Nippon.com. “Students had to go through the ordeal of the ‘exam war’ - years of intensive study to prepare for rigorous entrance examinations. But now the tables have turned, and the universities are competing with one another to woo applicants.”

Some are already bowing out. St. Thomas University in Amagasaki and Tokyo Jogakkan College in Machida announced late last year that they would be closing in March 2015 and March 2016 respectively. And Japan’s legendary “cram schools” have been affected as well. Yoyogi Seminar, one of the country’s largest exam prep chains, announced last fall that it was closing about 70% of its schools.

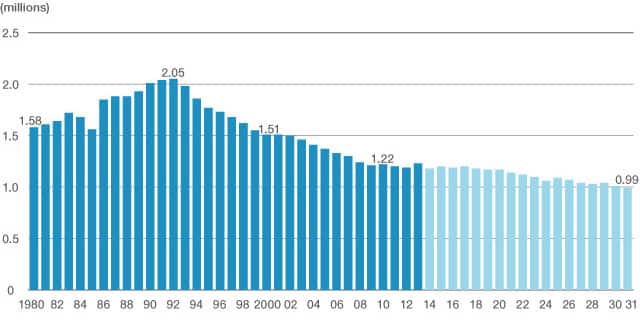

These institutions are caught between two contrasting and incompatible trends. While the number of Japanese university seats increased considerably over the past 20 years, the population of college-aged students has declined sharply over the same period. Riding the post-war baby boom wave, Japan’s population of 18-year-olds reached a high of 2.49 million in 1966. After cresting again in 1992, at just over 2 million, the college-age population has fallen by nearly half in the years since to reach 1.18 million in 2014. Nippon.com adds, “The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research predicts that this cohort will begin shrinking again from around 2018, falling below the 1 million mark to roughly 990,000 in 2031.”

Supply and demand and admissions requirements

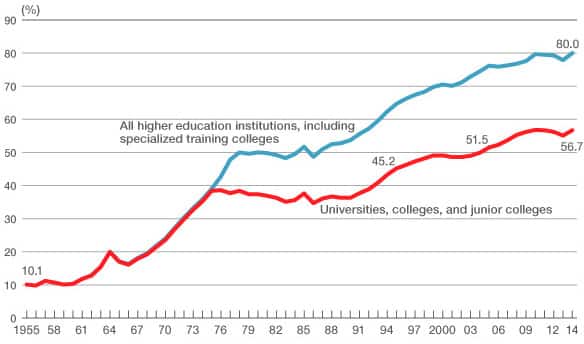

Participation in higher education in Japan has increased a great deal since the 1970s, at which point only about 36% of high school leavers went on to post-secondary studies. The enrolment rate (that is, the percentage of college-aged students engaged in higher education) stood at 56.7% in 2014 - more like 80% if vocational schools and other specialised training colleges are factored in. As Nippon.com puts it, “By around 2000 Japan had already entered an age of “universal” access to higher education - meaning that everyone can go to college as long as they are not picky about the school or faculty.”

The language question

We noted earlier that language acquisition is a major motivating factor for Japanese students’ interest in study abroad. In an era where Japanese students have ready and easier access to higher education at home, it may be that language and cultural travel will occupy an even greater place in overall outbound mobility from Japan going forward. Previous reform proposals have called for the introduction of English language studies at earlier levels of education, and English proficiency scores for Japanese students suggest that much needs to be done in this respect. The latest results, released earlier this month by MEXT, are based on proficiency testing of third-year high school students at 480 public schools across the country. The tests were conducted in summer 2014 with roughly 70,000 students and found that proficiency levels were below government targets across the board. The off-target results have triggered some criticism of the country’s approach to language instruction, including from The Japan Times: “For students to really function in a language, they need active and regular practice in producing meaningful, content-filled communication. Communication that contains meaningful content connects language study with students’ innate curiosity and motivates them to keep learning...The disappointing results show those conditions have yet to take hold in most public classrooms.” There are a number of elements mingling here, including a growing interest in study abroad (and foreign language study in particular), greater access to higher education at home, and persistent challenges in English language learning within Japanese schools. It seems clear that these factors will play an important role in shaping the level and nature of Japanese demand for study abroad in the years ahead.