What students want: The top decision factors for study abroad

The following article is adapted from the 2026 edition of ICEF Insights magazine, which is freely available to download now.

More than seven million students are currently enrolled in higher education abroad. This number has more than tripled since the turn of the century, and it is expected to reach nine million by 2030.

Underlying this growth are different circumstances than in the past, including a changed student mindset about the value of education.

To be more concrete, let us put ourselves in the shoes of just one person: an upper secondary student in Vietnam. She is set to graduate next year and hopes to go abroad for university studies. Over the next few months, she talks with her parents and friends; spends hours online researching programmes, institutions, and destinations; and chats with student ambassadors and alumni on social channels. She attends meetings with her school counsellor and visits a local education agency as well. In no time, she has a longlist of potential countries, cities, universities, and programmes.

But now what? How does she narrow the field of options? What motivates her to apply to one institution versus another? These are the questions that determine the shape of international student mobility.

The want list is longer now

Traditionally, students have prioritised goals such as international and intercultural experience, foreign language acquisition, and the prestige of a degree from a particular institution.

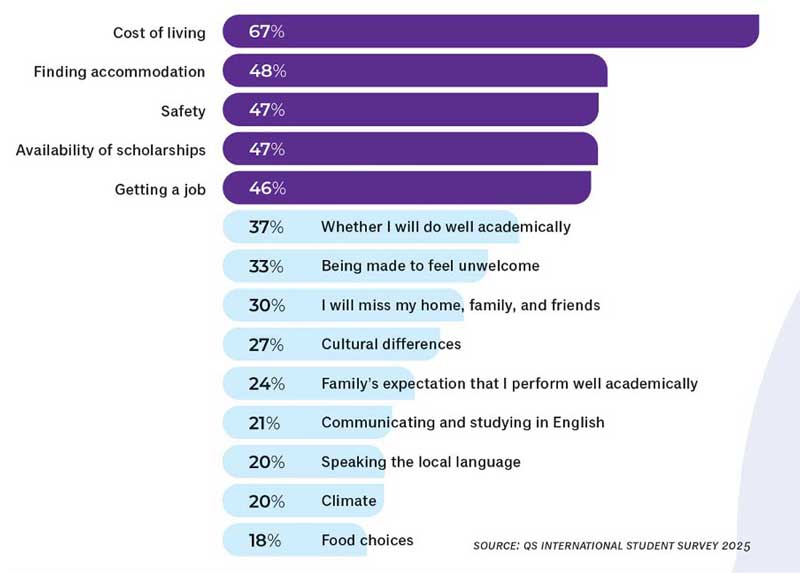

These goals remain influential. However, they are now often secondary to financial considerations and value for money. Global surveys by IDP, Etio, QS, Keystone, and Studyportals find that top concerns centre on cost of living, cost of studying, scholarships, work opportunities, and graduate outcomes, which are all linked to an emphasis on affordability and return on investment (ROI).

It isn’t that these concerns are new. Rather, what is important here is that affordability and ROI have risen significantly as factors that affect where in the world students decide to study, and in which programmes.

In some respects, this greater focus on ROI is changing the value proposition for study abroad. It affects, for instance, how students evaluate quality of education. For example, IDP’s Emerging Futures — survey conducted in March found that students increasingly equate quality of education with graduate outcomes.

Other indicators of quality – such as rankings – are still important. But IDP’s findings underline that students are looking beyond traditional indicators to ask, “What can I really expect?” “What am I going to get from this experience?” “What will this mean for my future prospects?”

Affordable destinations

The quest for affordability is a primary reason for the growing interest in destinations other than the “Big Four” (i.e., United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia).

As the Big Four have introduced more restrictive immigration policies, other countries – especially in Europe and Asia – have opened wide their doors. And it just so happens that many of these countries offer relatively low costs of study and living.

The following table provides a summary of undergraduate fees and accommodation costs in selected destinations, and it illustrates significant price gaps across the international education market.

We should note that costs for an individual student may still vary quite a bit within a given destination. Some fields of study are more pricey than others, smaller towns and cities are less expensive than major urban centres, and some students will have scholarships or other financial support from their host institution/country or home country. But the table’s broad comparisons reveal the wide spectrum of choice available to students with various budgets.

Factors affecting ROI

Costs of study and living are only part of what students consider when evaluating where to put their investment in study abroad. Students also look at available scholarships, the number of hours per week they can work while in their programmes, and the length of time they can work in a destination after graduation.

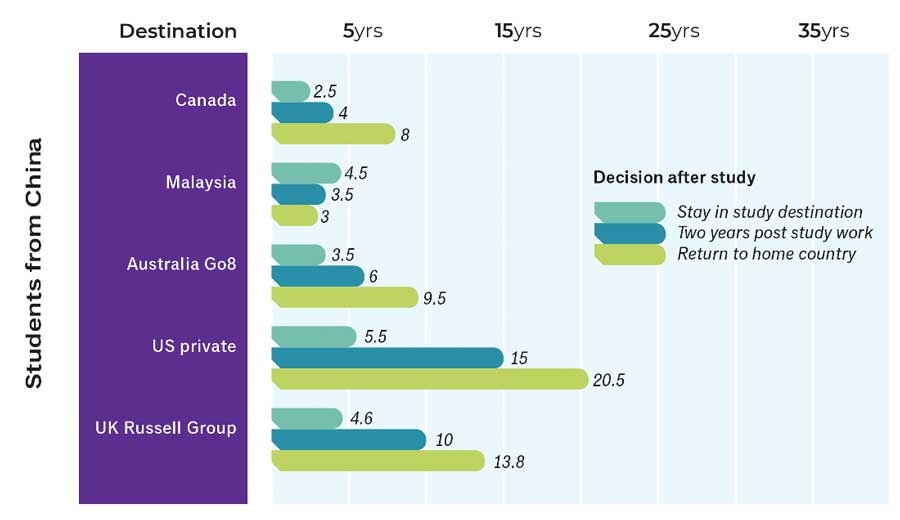

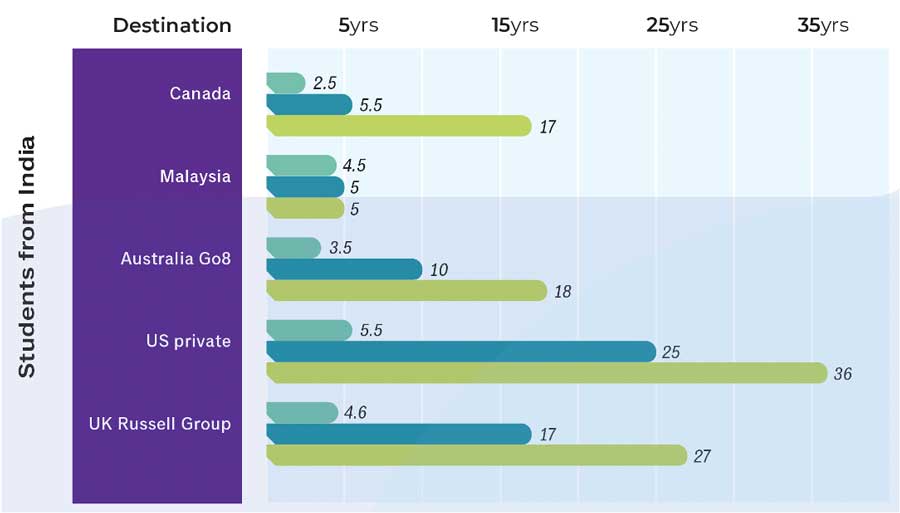

A recent analysis by INTO University Partnerships shows that beyond programme and institution choice, students’ post-study decisions – e.g., whether to emigrate, work for a couple of years in the destination country after graduation, or return home immediately – bear considerably on the time it takes to “earn back” the cost of an overseas education.

An undergraduate student from China, for example, who studies at a Go8 institution in Australia could expect it to take 3.5 years to recover study costs if they remained in Australia, 6 years if they worked for a couple of years before returning home, and 9.5 years if they went straight home after graduation.

But for an Indian student enrolled in that same Go8 university, it would take much longer to recover the cost of study unless they remained in Australia for good after completing their programme. In fact, it could take 18 years if they returned to India immediately after graduation, in part because the salaries afforded by the Indian labour market are often lower than in China.

Even across the two countries of origin and the five study options outlined on these charts, there is a tremendous range in that earn-back period. Now extend that to more countries of origin and destinations, and you get a sense of the complexity of decision-making facing students today.

INTO’s model also underlines the high stakes associated with a student’s choice of where and how they study. Their decision has serious implications for their future prosperity and wellbeing.

What is driving price sensitivity?

Macroeconomic trends such as trade wars, conflicts, and global warming-induced calamities such as droughts and flooding have a wide geographical and financial impact.

Consumers in both advanced and emerging markets are experiencing the effects of these global events. Inflation, rising food and housing costs, and rapidly changing labour markets are among the factors that impinge upon families’ disposable income.

The other factor in play here is that the composition of the international student body has shifted quite a bit over the last 10 or 15 years, and it's continuing to shift in terms of where students are coming from.

In 2010, there were just about four million students abroad in higher education. Just under a third of those were from China. And as I said earlier, China was the driver of global growth in international mobility for a couple of decades.

Just think for a minute about the profile of those students coming out of China. They're supported by a burgeoning economy, by an exploding middle class. They were self-funded, they were able to return to their home country and have an expectation of a higher earning potential.

In 2024, with more like seven million students abroad in higher education, only 14% of that total now comes from China, another 19% from India.

And indeed, the lion's share of that international student body writ large is now coming from South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

This includes a greater mix of students who are loan-funded or who are funded with family support or by scholarships. They come with very different needs and expectations. And, as Tim's work demonstrates to us, they have a different earning potential at home. So that ROI calculation is necessarily different, depending on where you are coming from.

The foreign degree premium

A key factor influencing international student mobility is the value that students, families, and especially employers place on a foreign university degree. This value is in itself integral to the calculus of the expected ROI from study abroad.

Several determinants affect the premium linked to foreign credentials versus degrees earned at home. The weight given to each may vary according to the student’s home country. For example, if the student’s domestic higher education system is seen to be of poor quality and incapable of improving career prospects, then a foreign degree will carry more of a premium.

Similarly, if the domestic higher education system has limited capacity and cannot produce enough skilled graduates for a growing economy, there is an aspect of scarcity that enhances the competitiveness of degree holders generally and graduates of foreign institutions in particular.

This premium, however, is not in a steady state. The value of foreign credentials tends to fall if there is an increase in the number of foreign degree holders (which erodes the scarcity premium). It also tends to decline when the quality of the domestic higher education system improves (which narrows the “quality gap” between foreign and domestic credentials).

China is perhaps the best contemporary example we have in terms of how that foreign degree premium can shift over time.

From the late 1990s through the 2020s, capacity and quality in the Chinese higher education system grew at an unprecedented rate. Over roughly 30 years, gross enrolment rates rose from below 10% in 1998 to above 50% as of 2024.

Chinese tertiary institutions enrolled approximately 50 million students in 2024, making China the largest higher education system in the world.

Years from now, when we try to pinpoint when the ground really shifted in China regarding the value of foreign degrees, we might think of the Chinese artificial intelligence (AI) company DeepSeek.

Not only did DeepSeek develop large language models (LLMs) considered to be highly competitive with leading generative AI models (e.g., OpenAI’s ChatGPT-¸ and Google’s Gemini), but it also put its high-grade AI product into the market at (reportedly) less than 10% of OpenAI’s cost.

This arguably makes DeepSeek one of the most important and highest-profile technological advancements to come out of China for some time.

The story behind the story, however, is that there are almost no foreign graduates on the DeepSeek team. Every single member of the team completed their undergraduate degree in China, and of the 24 postgraduate degrees held by DeepSeek team members, only two were earned outside China. “This would not have been the case 10 years ago,” says Matt Durnin, a consultant in higher education and principal at Nous Group. “Go into a large or influential Chinese technology firm and you would’ve at that time seen many more ‘sea turtles’ (i.e., foreign-trained returnees). They’re less valued and less emphasised in key industries than they used to be.”

This doesn’t mean that there are no longer opportunities for foreign universities to recruit in China. Far from it. But it does mean that Chinese students now assess the value of foreign degrees differently than they did even 10 years ago.

The example of China illustrates that the perceived value of a foreign qualification can change over time.

Most importantly, it suggests that for an institution or programme to retain its premium, it must deliver outstanding student outcomes.

Graduate outcomes

Promoting great student outcomes is an opportunity that is within reach for virtually any institution. It happens as well that our understanding of career services – especially when and how they are provided and the value that they represent for students – is changing quite a bit. The range of services will vary from institution to institution, but it typically includes career readiness workshops, assistance in interview preparation and resume writing, counselling, networking events with employers, internships, and job fairs.

A crucial question for institutions is how best to provide solid career services before, during, and after studies to students from around the world. A one-size-fits-all approach cannot accommodate the reality that there is a huge range of international student profiles.

At the ICEF Monitor Global Summit held in London in September, presenters and attendees discussed this very question. Sanam Arora is the chair of the National Indian Students and Alumni Union (NISAU) in the UK, and at the ICEF Monitor conference, she emphasised the place that career outcomes have in the hierarchy of student decision-making inputs:

“Seventy percent of Indians choose a destination of study on the basis of overall employability, and they have historically seen the UK or US in particular as a launchpad for global careers. In that sense, the definition of what it means to be educated has fundamentally changed. Universities that realise they’re not just here to educate, they’re here to be that global talent launchpad, will really ace this going forward.”

She continues: “Before I graduate, I want the university to help me prepare for a successful life. That is what I think of when I think of career services, because success in a career is not that different than success in life. Sometimes career services is seen as something that is off to the side or in a corner, but really it needs to be embedded end-to-end throughout the entire student life cycle.”

A longer window for career supports

Career services used to be introduced as a transition support for soon-to-be-graduates. Now, the window for career supports might begin even before the student has an admissions offer. For example, an institution might send information to applicants (or even pre-applicants) about internship programmes, and it might also offer pre-admission courses or career-readiness training.

At City St George’s, University of London, career services begin as soon as a student has received an admissions offer. The prospective student with the admissions offer may not convert into an enrolment for months, but the university recognises the competitive edge gained from giving that student access to career services right as they are choosing where to study.

Offering career supports at the pre-enrolment stage engages students in the areas they value most, and it draws them to a decision more quickly. If a student has offers from multiple universities, they are most likely to narrow their focus to the one that best highlights post-graduation outcomes.

What’s more, students who have received career-based information before they enrol are more likely to arrive on campus feeling positive, prepared, and informed.

Career services can also extend beyond the last day of a study programme. The University of Southampton, for example, provides career supports up to five years after graduation. The University of Edinburgh takes the idea even further by offering lifelong career support to alumni through a Career Services and Alumni Services platform that includes access to online resources and advice, career events, networking opportunities, and individual counselling support.

In this context, many students will also place a premium on work integrated learning, such as co-op or practicum placements. We have seen this becoming a bigger part of post-secondary offerings in recent years and I think this is a trend we can expect to continue as well.

The problem with numbers

It is widely acknowledged that there are significant data gaps across international education. In most countries, institutions generally don’t have enough information on how students are recruited; what they choose to study; how they perform in their studies; whether they graduate and how long it takes them; how often they obtain jobs linked to their programmes; and to what extent they are satisfied with their career outcomes.

This poses a significant problem for international educators who hope to develop evidence-based strategies for recruitment and retention. But lack of data is an even bigger problem for students, because data is what they want and expect when making study abroad decisions.

US institutions have an edge. “We are swimming in data,” says Dr Di Maria. “We have data on everything because we’re required by the US government to track what students are doing. More accurately, there’s a requirement to report on the activities. There’s not necessarily a requirement to report on success. But at our institution, we’re tracking both. So that allows me to know that 93% of our graduates are employed and/or pursuing further education within six months [of graduation]. We know the salaries. We know that about 60% of our students interned first at the company where they are now employed. We know 75% of our graduates stay in Maryland and 83% in the Capital Region (Washington, D.C., Maryland, and Virginia).”

Any of us reading those proof points knows how compelling they are for prospective students, current students, alumni, institutions, employers, and parents alike.

This brings us full circle to where we started. If career outcomes are the top priority for international students, it follows that institutions should prioritise outcomes in recruitment strategies, programmes, and services. Collecting better data on student success and graduation will go a long way towards achieving that alignment…and towards giving students what they want.