What is behind the dramatic expansion of the international schools sector?

- There are thousands of English-medium international schools in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, and the sector continues to grow quickly

- A dominant priority for many parents opting to send their children there is to see them prepared for English-language university programmes abroad

A new ISC Research white paper counts 13,180 English-medium international schools around the world as of July 2022. These schools – which are especially attractive to parents who feel they need more than English-language tutoring or extra lessons to prepare their children for university – enroll 5.9 million students aged anywhere from 3 to 18 years, with an average annual tuition of US$10,100 per year. That average, however, is heavily influenced by the higher end of the pricing spectrum:

“By country, this annual average can range from as high as US$30,000 to attend an international school in Algeria, to US$120 to attend an international school in Somalia.”

No matter what the exact price point, parents are often paying a lot more than they would for their children to attend a public school. There are several reasons parents choose the steeper price of an international school, which the ISC paper outlines and which we will summarise in this article.

ISC Research clarifies the type of international school being referred to in the white paper:

- “A privately operated school that delivers a curriculum wholly or partly in English to some or all of its students aged between 3 and 18 in a country where English is not an official language;

- OR a privately operated school that delivers a curriculum other than the host country’s national curriculum wholly or partly in English to some or all of its students aged between 3 and 18 in a country where English is an official language.”

A growing number of English-medium schools also teach additional languages.

More focus on individual students

Students at international schools tend to receive personalised instruction from teachers – mostly as a result of a lower student-to-teacher ratio (average ten students per teacher, in contrast to an average of 60 children per teacher in public schools in China and 50 per teacher in India). ISC Research says this allows for “more potential for student voice, and fewer behaviour and class management demands.”

With smaller class counts, there is an enhanced setting for English-language immersion – and an immersive environment for language learning (as opposed to one-on-one tutoring, for example) is often thought to be helpful to faster language acquisition.

Preparing students for study abroad

Many parents have an eye on the future when they opt for the higher fees of elementary or secondary international schools. ISC Research notes,

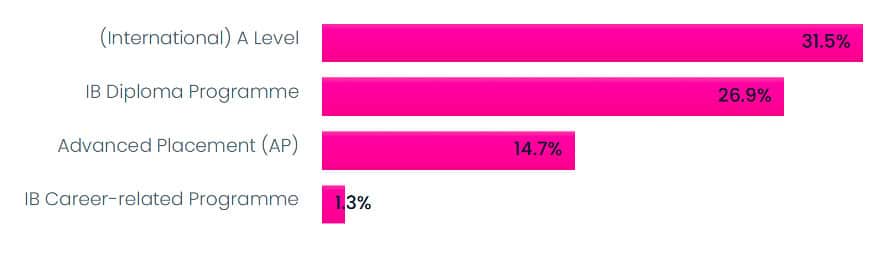

“The teaching and learning approach, exit examinations and leaving certificates offered by international schools are commonly accepted by the majority of the world’s higher education institutions including the highest ranked universities, as well as most multinational companies.”

While many parents dream of an elite higher education for their children, the white paper points out that,

“Reputable international schools, while supporting destination success for their students, also encourage a ‘best fit’ approach for future pathways to address the strengths and goals of each individual student. This can conflict with the ambitions of some parents who look to their child’s school to fulfil their personal dream of a child at Harvard.”

Schools that are responsible in this way are also good partners for foreign universities who want to enrol only students with the best chance of succeeding in their programmes.

Another way in which international schools can prepare student for study abroad – especially in the West – is that they opt for a holistic philosophy of learning where extracurricular activities, sports, the arts, volunteerism, etc. are complements to academic courses. ISC Research notes that,

“In some countries in Asia, this holistic approach can be dramatically different to the narrower curriculum, rote and didactic approach to learning, and highly pressured examination systems required by government-funded schools.”

What parents value

ISC Research conducted a qualitative survey among 51 people representatives at internationals schools in 33 countries – 91% of whom were senior leaders at the schools. When asked about what parents value the most, the respondents most frequently cited international schools’ “teaching and learning, international curriculum, community, facilities, and international context.”

Regional characteristics

The number of English-medium international schools has grown substantially in Southeast Asia: 1,905 in 2022 versus 1,528 in 2017. Many schools of these schools are in Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore. The white paper states, “Facilities in international schools are, in general, dramatically better than most government and domestic private schools throughout South-East Asia.”

In the Middle East, the UAE is notable for how many international schools it hosts, with almost four in ten students (38%) enrolled in international schools in Western Asia found in the UAE.

In Africa, going to an international school can be the difference between having or not having an Internet connection, or being able to tolerate extreme heat or having to leave early because of that heat. Graham Carlini Watts, an international education consultant and Director of Professional Learning at the Association of International Schools in Africa, notes,

“In some countries, international schools are the only schools that can afford good internet access, and in Nigeria, which has introduced planned electricity load shedding (power cuts) due to supply issues, international schools are often the only schools that can afford generators to power air conditioning.”

Mr Watts also points out that COVID-related technology advances in African international schools are helping to retain a large pool of qualified students for study abroad:

“Thanks to COVID, the tech is set up and the teachers are now sufficiently competent to enrich teaching and learning, and to support hybrid learning where necessary if it means a school not losing a child. It’s a brave new world and I think these types of technology-rich teaching and learning innovations will remain in the region.”

For additional background, please see: