Tracking fundamental shifts in the international schools market

- Once serving primarily a single market segment (i.e., Western ex-patriates living abroad), international schools are now accommodating multiple segments and evolving as a result

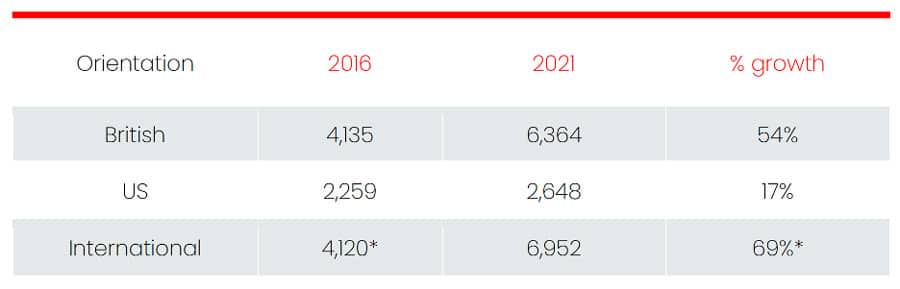

- Demand for “internationally minded” education is growing more quickly than for education with a more traditional Western (British or American) orientation

According to a new report from ISC Research, the profile and needs of the typical international school student and their family have changed substantially over the past 40 years. This creates new expectations, opportunities for expansion of the market, and demand for evolved curricula, teaching methods, and overall orientation. As a result, internationally oriented schools are growing more quickly than those with an exclusively British or American focus.

The report, aptly titled The International School Student Profile, draws upon proposals from the new UNESCO Reimagining Our Futures Together report to explore whether international schools are meeting the needs of students today.

ISC uses the following criteria to define an international school:

- If the school delivers a curriculum to any combination of pre-school, primary or secondary students, wholly or partly in English outside an English-speaking country.

- Or, if a school in a country where English is one of the official languages, offers an English-medium curriculum other than the country’s national curriculum and the school is international in its orientation.

Rapid growth, especially in Asia

As of July 2020, there were 11,616 international schools globally with a combined enrolment of 5,984,000 students aged 3 to 18, representing roughly 20% growth in the number of schools over 2018 and 17% enrolment growth.

Asia is the hot spot for the expansion of the market. Just over six in ten of all students (62%) enrolled in international schools in 2020 were enrolled in international schools in Asia. In South Asia particularly, enrolment in 2020 was up by 65% over 2015.

Fascinating evolution of the market

The evolution of international schools is tied in many ways to their purpose and audience. The first ones (in the 20th century) served the “direct educational needs of a small group of expatriates,” e.g., oil field workers from an English-speaking country living in a non-English country who wanted to educate their children in English and according to Western ideals.

Eventually, the market for international schools broadened to include local families who were often wealthy, pleased with the option of a school located close to home rather than a boarding school abroad, and interested in seeing their children’s K-12 education lead to placement in a well-respected English-medium university.

There’s now been a further expansion of the potential market: families in a growing number of countries who may not be in the highest household income stratum but who still want to send their children to an international school knowing that this may increase chances of obtaining a place in a reputable university. ISC notes,

“Today an international school education is high on the list of priorities for many families who can afford it. The result of this is that, whilst the market still caters for Western expatriate families, demand for places is mostly fuelled by local families and expatriate students from a much broader range of originating countries. This has prompted the growth in demand for international schools at a fee point accessible to more families. As a result, more international schools are being established, or are adapting their fees, with the purpose of meeting the needs of a mid-market fee sector.”

The expansion of the sector is thus tied to more flexible fee structures that can accommodate more market segments. An ability to offer alternate platforms for learning is also increasingly important, especially as a result of the growth of online learning in the age of COVID. ISC noted last year in its Global Opportunities report that,

“As families seek more affordable education options, and as schools feel the pressures of operating in an increasingly competitive market, growth will be driven by schools’ capacity to provide quality, affordable education using multiple learning options and platforms. This introduces a much larger population to international education, not only increasing overall demand, but also acting to ensure quality provision and a diverse student population.”

Demand for international outlook growing

Globalisation has opened up desirable career opportunities in a much wider range of countries and today’s employers are looking for candidates with a global understanding of geo-politics, economies, networking, cultural nuances, and more as they strive to open up more markets around the world. As a result, demand is growing for “internationally minded” schools with international curricula and learning ethos, as you can see from the ISC report chart below.

What does it mean to be internationally minded?

Decolonisation movements are also beginning to have an impact on government regulation of international schools and pushing the idea of a school’s being "internationally minded" from a fairly vague concept to a more concrete set of expectations. For example, in Vietnam, where the number of international schools has been growing relatively quickly in recent years, the government now (as of 2020) mandates foreign-invested international schools “to deliver compulsory Vietnamese language and culture studies to the Vietnamese students in international education.”

More broadly, ISC Research found in 2020 that 33% of international schools are bilingual, offering English as one of the main languages of learning. “Most of these schools are located in countries where English is not one of the official languages but where demand for an international education in English is high.”

ISC also mentions youth-led groups such as the Organisation to Decolonise International Schools (ODIS) and Reset Revolution. These groups are calling on educators to modernise their curricula and operations. Reset Revolution’s cofounder, Kotoha Kudo explains:

“I definitely think my education has helped me to understand different perspectives and different cultures, but I do think there should be more resources, teachers and leaders representing the views of many different people, and especially relating to the host country … Educators have to be the ones to make sure the curriculum, structure, and peace-conflict management strategies change, and that uncomfortable topics are talked about. Don't scoop them aside just because they're uncomfortable – if you're uncomfortable, that probably means they're important topics.”

For additional background, please see:

Most Recent

-

British Council says student recruitment to UK higher education will get a boost this year from South Asia and the “Trump effect” Read More

-

New Zealand expands post-study work opportunities for international students Read More

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More