The relationship between currency exchange and student mobility

It has been a tumultuous year for the world economy, which in many quarters is still recovering from the deep economic shocks of the 2008 global economic crisis. A number of markets, Greece and Brazil among them, are struggling with ongoing challenges of declining economic growth, low commodities prices, high inflation, and weak balance sheets. Sparking a fresh round of anxiety, the Chinese stock market crashed in late June and stock values fell off by as much as 30% before the government intervened to try and halt the slide. And in August, the Chinese central bank took the highly unusual step of devaluing the yuan (officially, renminbi or RMB), not once but three times during a month that left many observers wondering if the Chinese economy was in for a hard landing this year. Needless to say, financial markets do not deal well with fear. Concerns over these ongoing economic challenges have placed a lot of pressure on local currencies and produced some notable shifts in foreign exchange rates in 2015. In particular, many emerging market currencies have weakened over the past year against the US dollar and British pound. This has led in turn to more speculation as to how prevailing currency trends over 2014 and 2015 may influence student mobility going forward. There is of course a linkage between foreign exchange and demand for study abroad. It arises from the simple fact that if your home currency weakens against the currency of the study destination you have in mind, your study programme effectively becomes more expensive – you need more of your local currency to pay tuition and living costs in dollars or euros or pounds while abroad. In this sense, foreign exchange rates play a role, sometimes a key part indeed, in shaping demand for study abroad. There is debate, however, about how much of an effect they have, or, more to the point, how much a currency needs to shift before demand for study overseas is significantly affected. During the Asian financial crisis of 1997, for example, the baht, ringgit, and won (among other currencies in the region) lost as much as half their value against the US dollar. At the time, that sharp drop led to corresponding and immediate declines in student numbers from such markets as Thailand, Malaysia, and South Korea. The economic pressure in 2015, however, is different. It is broader, affecting a wider variety of emerging markets around the world, and, to this point at least, most currencies have not been affected as drastically as was the case in Asia in the late 1990s. That said, some have argued that even a modest change can be expected to impact student numbers. “Emerging markets have long been a driver for internationally mobile study around the world,” says Todd Maurer, a founding partner with US-based financial analysis firm Sinica Advisors. “[I do] not see how the international education market will be immune to dramatic changes in currency values and their impact on affordability across an international student base largely drawn from developing economies,” he adds. “To be sure, student decisions are not only based on affordability but also programmatic quality, academic reputation, geographic proximity, prospects for future immigration and other intangibles. But for many students and their families, a difference as much as 10–15% in cost can hit hard on household budget decisions.” However, there is another point of view that plans for study abroad – especially in cases where students are intending longer-term studies for secondary school or degree completion – can tolerate a certain level of fluctuation in foreign exchange rates. Such programmes are planned well in advance, with funds set aside over time, and are less sensitive to short-term changes in currency values. This is not to say that other programmes are not more exposed to currency effects. Short-term language studies, for example, that may be planned within a shorter time frame (and that may be less differentiated from general language studies in other destinations) tend to be more sensitive to shifting foreign exchange rates. Indeed, there have been reports of aggressive discounting among some language programme providers this fall. This reflects underlying factors such as intensifying competition and increasing commoditisation in language travel, but these discounting practices are also likely intended to offset some of the cost-competitive pressures arising from weakening currencies in sending markets.

Crunching the numbers

It is fair to say there have been some important shifts in world currencies over the last few years. As we noted earlier, the Chinese yuan fell in value earlier this year. The Indian rupee has declined significantly against both the US dollar and British pound over the last three years. And the Russian rouble had a very challenging 2014 to say the least.

Most recently, both the yuan and rupee have stabilised over the last three or four months and the same could be said of the rouble as well.

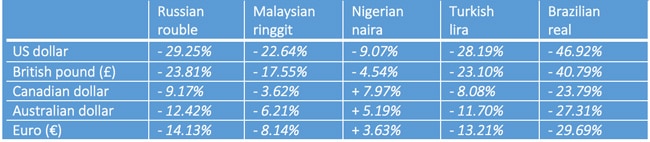

For the most part, however, the real effects of currency fluctuations are not to be found in such short windows of time. When we take a closer look at a larger sample of key emerging markets, below is the picture that emerges for the last 12 months in relation to a range of leading destination currencies.

- All of the emerging market currencies in our sample are down against the US dollar and British pound.

- With the exception of the Nigerian naira, this decline is fairly substantial with an average decrease for the remaining currencies of 31.75% against the dollar and 26.31% against the pound.

- Within our sample, the Brazilian real has registered the sharpest decline in value over the past 12 months, and again the drop-off is most acute in relation to the US and British currencies.

- With the exception of the real, the declines for most other currencies in the sample hover at or slightly above 10% against the Canadian dollar, Australian dollar, and Euro.

In relation to these, we can also note that the Chinese yuan declined by 3.72% against the US dollar, and was essentially flat against the pound over the same period. The rupee, meanwhile, had a relatively stable year: it fell by 2.45% against the pound and 6.93% relative to the US dollar. Over the same period, the Euro lost about 13% of its value in relation to the American currency.

Thinking again in broad terms, there are some likely implications arising from these one-year trends. First, study in the US and UK has become significantly more expensive – between 20–40% more – for students from a number of important emerging markets. We might expect to see more prominent offers of financial aid by providers in both countries, and, in the case of more commoditised programmes, more aggressive price discounts or the introduction of new, specialised programme offerings.

We can also anticipate a shift in study plans for some students away from those now-more expensive destinations and toward more affordable choices, including Canada, Australia, other European destinations, or elsewhere. This has already begun to play out in the case of Brazil this year where the emphasis is shifting to hosts such as Canada and even more so to still more-affordable destinations such as Malta, South Africa, and Ireland.

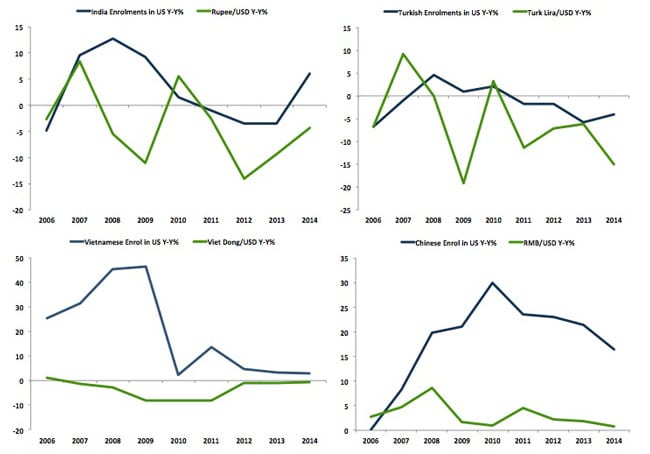

This idea is further borne out by analysis from Mr Maurer at Sinica. In the following charts, he maps the behaviour between year-over-year percentage changes in currency values against the US dollar and corresponding percentage-term growth in enrolment from selected markets.

As he notes, “The results show clearly that declining enrolments are correlated with sustained local currency weakness against the US$ over the historical period. In fact, enrolment declines in these examples (apart from China, which until recently has been mainly appreciating against the US dollar) were almost always preceded by local currency declines.”