English language training in India pegged for significant growth

With evidence demonstrating that English language fluency opens the doors to greater employment opportunities and higher income among its graduates, demand for English Language Training (ELT) is on the rise in India. India’s government regards improved English proficiency as a key plank in maintaining the nation’s competitiveness in a fierce global marketplace. And, with India revamping its education policies and signaling a new openness towards international collaboration, foreign partnerships in the provision and delivery of ELT programmes are only expected to grow.

English proficiency levels an issue

A 2012 report by the British Councilnoted that while English is widely perceived as a valuable life and employability skill among Indians, India ranked only 14th out of 54 countries in a global survey of English proficiency conducted by EF (Education First) placing it in the category of “moderate proficiency”. (Note that the 14th-place ranking refers to an earlier edition of the proficiency survey. The latest EF survey ranks India 25th of 63 nations.) The report also quotes David Graddol, author of the book English Next India, who argues that a shortage of English language teaching in schools has hindered proficiency levels and is causing India to lose its competitive edge to other developing countries. Indian universities fall far short of rival countries in teaching and research quality, he says, and "poor English is one of the causes." The report’s authors note as well that Aspiring Minds, a company that focuses on assessing student employability, found that about 78% of 55,000 Indian graduates surveyed in 2011 struggle in the English language.

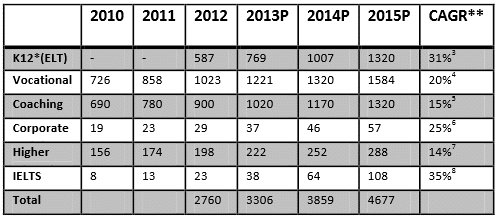

The report projected that the ELT market would grow in size from US$2.76 billion in 2012 to US$4.67 billion by 2015.

Vocational training was valued as the most attractive segment in 2012, with a market share of 35%, followed by the coaching and K-12 segments.

Demand driven by higher incomes, competitiveness

Last year, we reported on the release of a study that found that Indians who speak English fluently earn up to 34% more than those who don't speak the language, confirming the link between English language proficiency and the scope for greater employment opportunities and better earning potential. Yet what else is driving the upsurge in demand? According to a recent article in Asia Briefing, the struggles with English proficiency among India’s workers is causing the country to lose its competitive advantage to rivals like the Philippines, particularly in the lucrative call centre sector. The article points out that the Philippines has overtaken India in recent years as the largest hub for call centres in the world, with more than one million Filipinos working in call centres and the broader Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) industry. Most of the increase in BPO activity in the Philippines has come at the expense of India, with the Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India (ASSOCHAM) reporting in 2013 that India lost over 50% of its BPO sector to foreign countries, costing the Indian economy an estimated US$25 billion. “The primary reason companies have moved their outsourcing from India to the Philippines is because Filipino employees often speak fluent American-accented English,” says the report. “While Indian employees are also known for good English compared to the rest of Asia, employers have found that the Indian accent can be hard to understand for some of their customers in the US and Europe.”

New regulations, initiatives to meet demand

Clearly, the provision of ELT services in India has not kept pace with market demand. This is set to change with planned reforms to India’s education system, in particular a new recognition on the part of the Indian government that internationalisation and greater collaboration with foreign providers are vital planks to achieving ambitious growth targets.

India announced earlier this year that it is drafting a new education policy, the first of its kind in over two decades.

An early release of related discussion themes includes:

- a renewed focus on internationalisation;

- digitisation of education;

- skills development.

These are all areas with potential opportunity for foreign providers. The policy process comes on the heels of signals by Minister of Human Resource Development Smriti Irani that she is willing to move forward on a foreign provider bill that’s been stuck in political deadlock since 2010. As we reported late last year, “In a bid to clarify the regulatory requirements for foreign institutions hoping to expand in India, the national government introduced the Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry and Operations) Bill in 2010. The Bill sparked a great deal of interest among foreign providers but was subsequently withdrawn in 2012 and replaced, in some respects at least, by new regulations introduced last year by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). Essentially an executive order under the administration of the University Grants Commission (UGC), the new regulations permit foreign institutions to establish branch campuses in India and confer foreign degrees.” The massive expansion of higher education in India is a notable challenge. The government has a stated goal to increase higher ed participation rates to 30% by 2020 from 18% today - a target that will require the creation of an additional 14 million spaces in the country’s tertiary institutions over the next six years. Such growth, according to the National Knowledge Commission, is projected to cost upwards of US$190 billion in order for the country’s education system to expand to meet this target. Growth of this scale and pace will likely only be done in collaboration with the private sector, and through a wide range of partnerships with foreign providers.

Some early successes

There are some early success stories in India’s burgeoning ELT sector. Kings Learning, for example, is a new ELT school targeting Indian nationals that has seen greater-than-anticipated demand for English language training at its centres in Bangalore and Chennai. Kings Co-Founder Tahem Veer Verma explained recently that demand was being driven by white collar workers who realised that good working English strengthens their career prospects. “There is a glass ceiling in English and if you don’t speak English, there is only so far you can go in the corporate world,” he said. “English is a social status symbol.” In another initiative, Hyderabad-based English and Foreign Languages University (EFLU) provides English language skills training to a range of Indian professionals - from defence personnel to Indian Foreign Service (IFS) probationers, corporate executives and government officials. Opened in 1958 as Central Institute of English (CIE), the university now offers M.A. programmes in English literature, English language teaching, cultural studies, linguistics and phonetics, and media and communication. It has linkages with 22 universities, mostly in Europe and the United States, and offers English training (and training in Indian culture) to non-Indian nationals. As these programmes attest, the demand among Indians for quality, globally-recognised English language training will only grow in the foreseeable future. India’s burgeoning middle and executive classes are fueling the demand, but the Indian government also recognises that in order to remain competitive globally - whilst also closing skills gaps at home - a focus on English language training is key.