Peak international education bodies in UK call for improved competitiveness in run-up to spring election

A recent British Council report paints a stark picture of the UK’s declining competitiveness as a global study destination. International enrolment in British higher education fell in 2012/13 for the first time in 29 years. And, while foreign student numbers rebounded modestly the year after, some of the underlying trends remain troubling.

Enrolment continues to fall from countries that figure to be major sources of international students in the decades ahead - notably India and Pakistan. Meanwhile, the marginal growth registered by the UK in 2013/14 is overshadowed by larger gains from its international competitors. “We are losing global market share,” said the British Council’s Jo Beall to the International Higher Education Forum convened in London last week by Universities UK. “Total numbers grew in the UK by about 3% in 2013/14. But in the US it was 8%, Australia 8%, and in Canada 11%.”

Dr Beall’s observations are echoed by British Council analyst Jeremy Chan whose recent report adds, “The UK’s market share among the four major host destination countries has fallen in each of the last three years, returning to levels last seen in 2008/09. More worrying, based on the latest UK study visa data from the Home Office, UK market share will likely decline further in 2014/15.”

Going to the polls

As it happens, 2015 is no ordinary year in the UK; it is an election year with the vote scheduled for 7 May. Immigration remains a hot political question in Britain but public sentiment running strongly in favour of tighter immigration controls, and with recent polls showing the Labour and Conservative parties locked in a dead heat, it may well be that neither of the leading contenders for power will take the chance to introduce bold new policy directions for immigration. Recent years have seen vigorous debate within the UK as to whether international students should be included in the government’s “net migration” targets, and a series of changes affecting student visas have been hotly contested by educators and students as well.

Bring on the manifestos

Against this backdrop, two peak bodies have released wide-ranging statements over the last two months calling for greater competitiveness and fairness in Britain’s international education sector. Both are squarely aimed at influencing debate leading up to the election as well as lobbying the country’s next government in the wake of the spring vote.

The first statement, A Manifesto for International Students, comes from the UK Council for International Student Affairs (UKCISA). It makes the point that recruitment to the UK has been significantly affected by government policy: “Over the last 2-3 years, international students have been caught up in the complex and contentious rhetoric of ‘cutting down on abuse’ and ‘reducing net migration’ and a range of increasingly restrictive rules and procedures have been imposed on institutions. There is therefore now widespread concern that the UK is not taking advantage of what is a rapidly expanding global market of strategic importance to the UK and will not be able to do so unless there are changes to our visa policies and the complex way in which the rules are currently administered.”

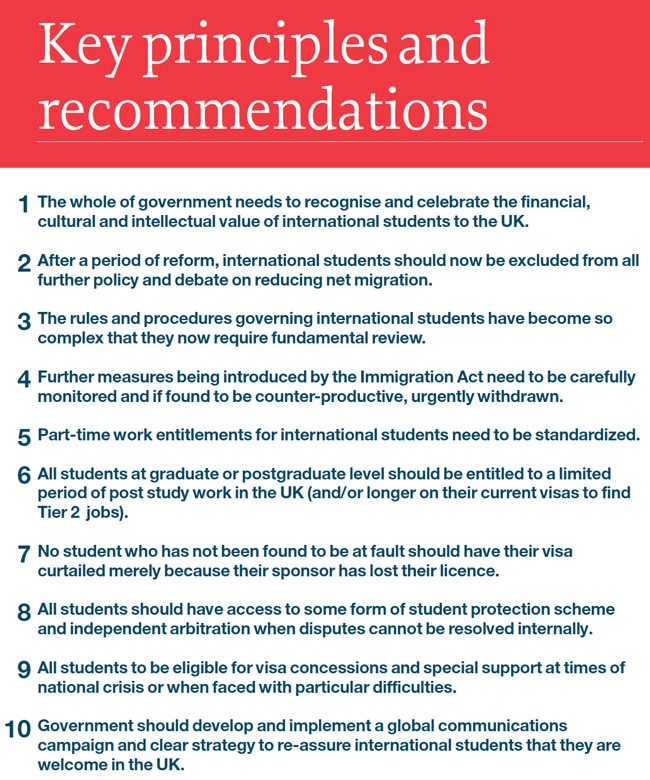

The manifesto sets out a series of ten recommendations designed to make the UK a more welcoming and attractive destination for qualified international students, increasing Britain’s share of the international student market, and advancing the country’s standing and influence in the world.

The recommendations (please see a summary table below) focus on greater cohesion in government policy, particularly with regard to immigration, and protecting the rights and interests of international students in the UK.

The statement makes the point that, prevailing British views of immigration aside, research shows that the public do not see international students as “migrants” and that a series of parliamentary committees have explicitly recommended that students be excluded from the government’s net migration targets. “This now needs to be accepted by government, as a matter or principle,” the manifesto concludes.

UKCISA's Chief Executive Dominic Scott has described the statement as a set of fundamental principles and recommendations “on behalf of international students and all those who work with them” and positions the manifesto as a “common agenda” to be shared within British education institutions and to be used widely in lobbying and advocacy efforts with government officials and members of Parliament. He adds, “We will be promoting the manifesto widely direct to international students to demonstrate to them that there is a community in the UK which is on their side and willing to speak up for their interests.”

“Competitive international student policy rests upon the strong foundation of an effective visa system. The current Tier 4 system has been undermined by a rapid series of changes, rarely subject to any parliamentary scrutiny or public consultation… It is time the whole system is fundamentally reviewed and radically redesigned with sector input to be effective, proportionate and properly fit for purpose.”

The manifesto argues that such a policy overhaul would be a key step to improving the UK’s attractiveness to international students, and to improving the country’s competitiveness in global education markets. Its more specific proposals for creating a more welcoming destination for internationally mobile students include:

- That foreign students be permitted to work part-time during their studies;

- That postgraduate students have the option to bring their families to the UK;

- That all students be allowed an unrestricted six-month work period after graduation, “followed by two years of structured work experience within a field related to their studies.”

As with the UKCISA manifesto, the purpose of the Study UK statement is clear. “We want to start a conversation and want to be engaged with that conversation,” says Study UK Director Paul Kirkham. That discussion has now been joined and is bound to continue through the election this spring and with the government it returns to Britain afterwards.