The growing case for building institutional links with India

India is planning a massive expansion of its higher education system over the next decade. The Indian government has a stated goal to increase higher education participation rates to 30% by 2020 from 18% today - a target that will require the creation of an additional 14 million spaces in the country’s higher education institutions over the next six years. Government spending on higher education amounts to about 1% of GDP currently, and the National Knowledge Commission has projected a required investment of up to US$190 billion in order for the country’s education system to expand sufficiently to allow it to reach its 2020 targets. An expansion of the scale and pace that is currently being anticipated will likely only be done in collaboration with the private sector, and, observers increasingly point out, through a wide range of partnerships with foreign providers.

Not just growth

The question goes well beyond the need to create a large number of additional seats. There are significant quality issues in higher education in India, and also persistent issues with respect to the employability of graduates. The country is concerned therefore with expanding its tertiary system, but also with improving equity of access and quality across the board.

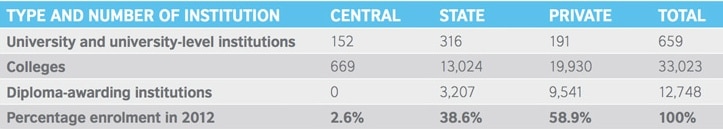

All of these ambitious and interrelated goals are amplified by the fact that the Indian system is massive. There are approximately 650 universities and more than 40,000 colleges and diploma-granting institutions. This large institutional field can be further categorised by funding source, whether central (e.g., national) government, state, or private. The following table gives a breakdown of all institutions, and the share of enrolment for each, as of 2012.

Regulatory environment

A leading Indian business association, the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), has produced another key report in collaboration with Deloitte India and with the backing of India’s Ministry of Human Resource Development. The Annual Status of Higher Education of States and UTs in India, 2014 (ASHE) adds an important perspective on the current regulatory environment in the country as well as the level and nature of foreign direct investment in Indian education. The ASHE report notes that although foreign investment in Indian tertiary education is permitted, at least in some respects, the interests of foreign investors and education providers have been frustrated by conflicting and confusing regulations. For example: “The [All India Council for Technical Education], which is the principal regulator for technical education in the country, in its regulations specifically prohibit direct or indirect foreign investment in [section 8 under Companies Act 2013] companies to act as sponsoring bodies of a technical institute which can offer courses in management, engineering, design, pharma etc. Similarly, the UGC Act which regulates university/college education in the country does not recognise 'foreign universities', which has led to a lot of uncertainty for foreign investors. It is pertinent to further note that foreign investment in a 'not-for-profit' company incorporated under section 8… of the Companies Act is subject to prior approval under [the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act]. This approval is issued by Ministry of Home Affairs and is a time consuming and tedious process.” In a bid to clarify the regulatory requirements for foreign institutions hoping to expand in India, the national government introduced the Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry and Operations) Bill in 2010. The Bill sparked a great deal of interest among foreign providers but was subsequently withdrawn in 2012 and replaced, in some respects at least, by new regulations introduced last year by the Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD). Essentially an executive order under the administration of the University Grants Commission (UGC), the new regulations permit foreign institutions to establish branch campuses in India and confer foreign degrees. There are, however, a number of eligibility requirements. Foreign operators of branch campuses in India must:

- Be not-for-profit;

- Have been in existence for at least 20 years;

- Be accredited by a reputable organisation;

- Be ranked in the top 400 in one of three global rankings: the UK-based Times Higher Education or Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) rankings, or the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Academic Ranking of World Universities;

- Offer course content as good as that offered via their main campuses;

- Not repatriate money earned on Indian soil or distribute profit or dividends to members.

CII points out as well that foreign providers operating branch campuses in India must “establish [the] campus through an association to be registered as a company under section 8 of the Companies Act, 2013.” The new Companies Act brings with it some new obligations for foreign-owned enterprises in India, including a requirement for a Resident Director and for funds to be held in trust or dedicated to corporate social responsibility programmes in India. Rumours persist that the Indian government plans to reintroduce the Foreign Universities Bill, more or less as it was originally tabled in 2010. But the timing of such a move remains uncertain, as does the point at which any such legislation would be passed into law.

In the meantime

The British Council picks up on this very point in its commentary: “Not a single interviewee believed that the Foreign Educational Institutions Bill would be passed in the medium future. Most interviewees suggested that the way forward for foreign institutions would be through bilateral institutional collaborations in research and teaching and not through foreign-owned campuses. Foreign institutions were advised not to wait for conducive legislation, but be more creative and flexible in their approaches to collaboration and business planning in India.”

CII concurs, adding in its report that, “Regulatory complexities and restrictions have driven foreign investors to seek alternative routes to enter the Indian higher education sector to operate in unregulated domain. A case in point is the concept of ‘twinning’ or entering into joint ventures and academic collaboration with Indian universities, without any commitment of capital [such as would be required to open a branch campus].”

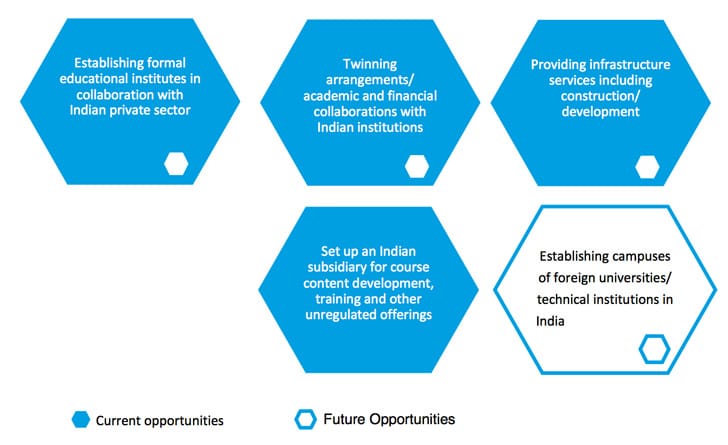

Both the British Council and CII commentaries go on to map a variety of ways in which foreign providers can engage in partnerships and linkages in India today while remaining adaptable to emerging opportunities, and shifting regulatory requirements, in the future. As the following graphic illustrates, those opportunities include a wide range of capacity building and service activities, most of which fall outside the range of regulatory requirements aimed at branch campus operations.