One third of new international degree students in UK transfer from partner institutions abroad

A recent guest post from Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE) researcher Dr Vangelis Tsiligiris explored the impact of transnational education (TNE) programmes on international student enrolment in host countries. Dr Tsiligiris observed dramatic increases in offshore enrolment in TNE programmes - such as articulation and joint programmes - in recent years and concluded that TNE is a distinct mode of education export that does not divert students from outbound student mobility.

And now a new report from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) extends the point in finding that a significant share of new international enrolments in the UK transfer directly from programmes delivered offshore by British institutions. The report, Directions of travel: transnational pathways into English higher education, estimates that “around 34% (16,500 entrants) of all international first degree entrants in England transferred in 2012/13 from programmes delivered outside England.”

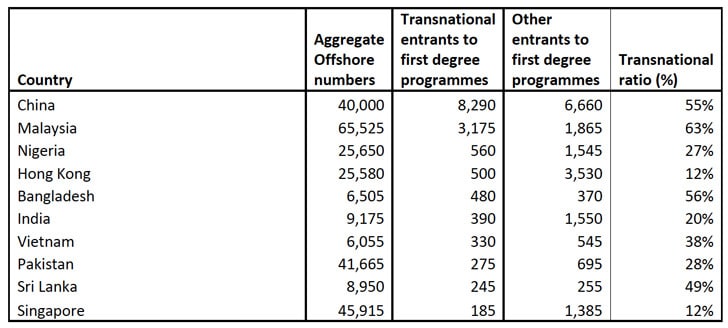

China and Malaysia accounted for the lion’s share of TNE transfers to the UK. More than half of the new entrants to UK degree studies from these two countries - 55% in the case of China (8,290 students) and 63% for Malaysia (3,175 students) - were recruited directly from UK-linked TNE programmes.

As the following table reflects, the two countries accounted for about 70% of all TNE-related enrolments tracked by HEFCE in 2012/13. There were, however, marked differences in the average term of study for these two leading source countries. Most Chinese students (66% of TNE transfers) expected to study for two to three years. More than half of Malaysian students (56%), meanwhile, planned to study for a year or less.

Paths to the UK

The HEFCE analysis considered four major routes through which TNE students enter undergraduate studies in England:

- Transfers from branch campuses overseas;

- Transfers from programmes delivered jointly with partner-institutions overseas;

- Credit transfer from UK-designed programmes delivered by an offshore partner;

- Credit transfer via other articulation arrangements with an international partner.

In his recent OBHE paper, Dr Tsiligiris reported that the overall enrolment in UK TNE programmes has grown significantly, rising from 192,205 students in 2008 to 337,255 in 2013 for an average annual growth rate of 12% over the last five years.

Other observers have pointed out the likely connection between the growth of such programmes and their increasing importance as a recruitment channel for host institutions. No doubt this relationship is particularly clear to the participating institutions, but the HEFCE report is notable for its attempt to analyse enrolment patterns more broadly.

For example, it looks in part at the correlation between TNE-derived enrolments and the average Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) tariff scores for UK institutions. UCAS provides application services for British universities and its tariff system is a way of scoring the academic qualifications of UK students for purposes of admission to universities in the UK.

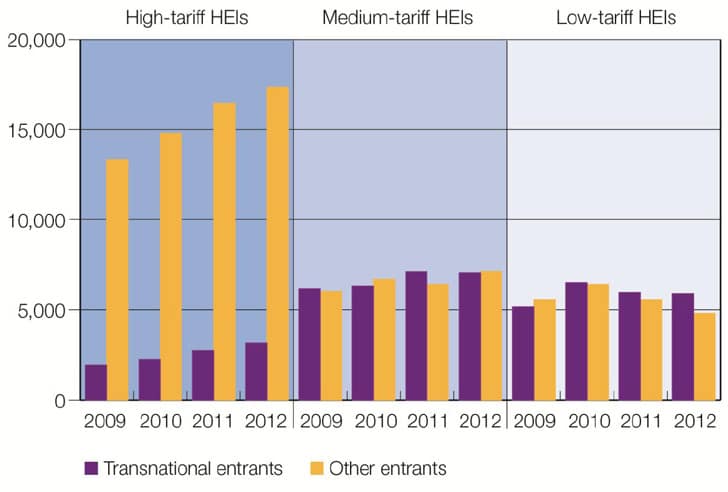

HEFCE points out that British institutions with high average tariff scores (that is, those in the top third of institutions according to the average tariff scores of their UK undergraduate entrants) are less reliant on TNE students than are those institutions with low average scores. “[Higher education institutions (HEIs)] with high average tariff scores have a lower proportion of transnational students: 16% (3,200 entrants) in 2012/13, compared with 55% (5,900 entrants) for HEIs with low average tariff scores. HEIs with medium average tariff scores have an almost equal split between their transnational entrants and those recruited through standard recruitment and other onshore pathways.”

This variability by tariff score group is reflected as well in the following chart, which shows the relative growth in enrolment for TNE-related enrolment as opposed to students recruited from all other sources.

Term of study

The growth in TNE-related recruitment has clearly been an important factor in building or sustaining overall international enrolment levels in the UK in recent years. There are, after all, significant efficiencies to be gained in recruiting via TNE programmes and partners. Most notably, they represent highly targeted recruitment channels that link transferring students strongly to the complete degree programmes of the host institution. However, there is a downside as well and that relates to the term of study.

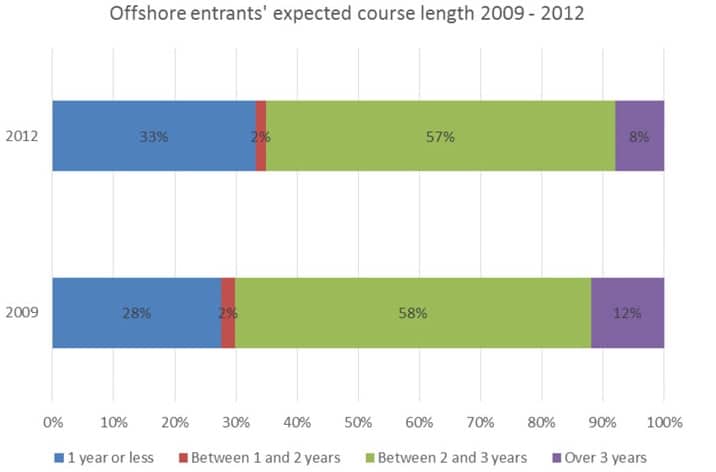

As we noted earlier, the average length of study for the two main TNE source countries for the UK - China and Malaysia - commonly ranges from one to two years. This is significantly less than a student who enrolls with a UK institution for an entire degree programme, and, as the following chart reflects, the near-term trend is towards shorter average periods of study for TNE students.

The question that naturally arises here is whether or not the relative efficiency of recruiting via TNE channels offsets the challenge of shorter study terms for TNE transfer students.

Part of the answer may rest with Dr Tsiligiris’ OBHE paper and its finding that TNE is in effect a separate mode of education export - one that attracts a different type of prospective student. Put another way, students that progress from TNE programmes offshore may never have pursued a full degree abroad in any case and so in that sense the TNE channel represents a means of reaching a broader pool of prospective students for at least partial degree studies abroad. Given the increasing importance of intra-regional mobility within East Asia, this prospect pool may increasingly include third-country students who travel from elsewhere in the region to another Asian country to study in a TNE programme linked to an institution in a more traditional study destination, whether the UK or otherwise. As HEFCE concludes, “HEIs embedded in the local education structures will most likely benefit in the long-run from increasing intra-regional levels of student mobility, and will have better access to deeper and more comprehensive collaborative partnerships with institutions in the region.”