Women increasingly outpacing men’s higher education participation in many world markets

It used to be that men were overrepresented in higher education, but that trend has been changing for several years now. In the 1990s, in many parts of the world, female students began switching places with their male counterparts as the most dominant gender in terms of higher education participation. In 2005, almost a decade ago, women represented 55% of the higher education student population in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) area – 1.2 women to every man – according to an OECD report published in 2008. The OECD then predicted that if the rate of women becoming more numerous than men in higher education continued:

"The inequalities to the detriment of men would be well entrenched at the aggregate level in 2025, with some 1.4 female students for every male. In some countries (Austria, Canada, Iceland, Norway, the United Kingdom) there could be almost twice as many female students as male."

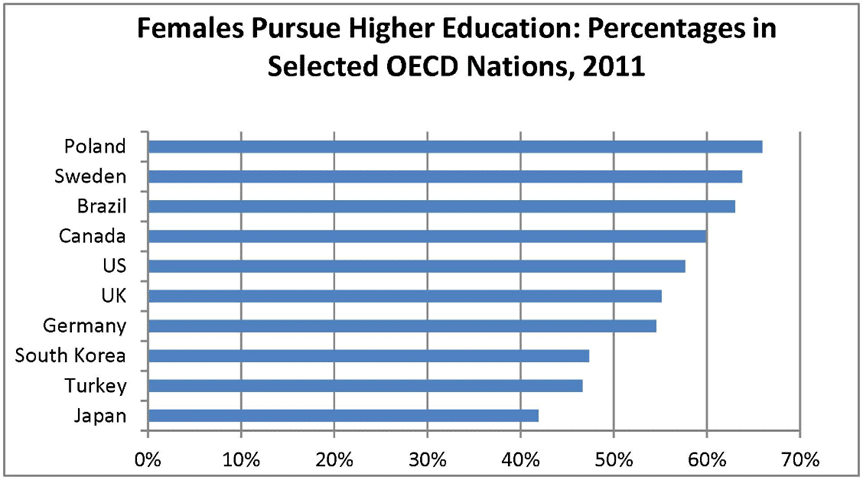

The OECD report, The reversal of gender inequalities in higher education, predicted that only four member countries would fail to have at least as many women as men by 2015: Japan, Korea, Switzerland, and Turkey.

The following chart updates the OECD’s mid-2000 predictions, showing the percentage of women in higher education in ten OECD countries as of 2011.

- In the UK, 376,860 women had applied for a place at university in 2014 compared to 282,170 men – a difference of a third (94,690, and up from 86,630 in 2013).

- In the US, nearly 60% of university graduates are women, plus 60% of master's degrees and 52% of doctoral degrees are awarded to women.

The same thing is happening in Canada, where 59% of Canadian undergraduate students are women, and where women’s overrepresentation is happening in almost every faculty, with the exception of engineering, computer science, and the physical sciences. Outside of the OECD countries, the trend toward more female students than males is also evident. In China and India, men still outnumber women in higher education, but not by much: women make up 48% of the university population in China and 42% in India. And in Jordan - like Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates - more women than men are enrolled in university.

Why the trend is occurring

The OECD report lists a number of hypotheses for why women are outpacing men in higher education participation. (It cautions, however, that almost all of these hypotheses are based on studies that contain either methodological limitations or that are contradicted by other studies.) The possible factors include:

- Women’s new ability to combine studies and work with family life, in many places;

- Decreasing discrimination against girls in families (again, in many places);

- Girls’ higher preparation for higher education, as evidenced by their test scores in secondary education;

- Girls’ higher aspirations to obtain tertiary degrees;

- The feminisation of the teaching profession and a learning environment more conducive to girls’ social and cognitive dispositions.

Of course there are countries where access to education for girls is far less guaranteed and even potentially fatal. Recently former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced a $600 million global plan to counter such obstacles and boost access to education for women and girls. Professor Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at Buckingham University, interviewed by the UK newspaper The Telegraph, adds these hypotheses toward answering the question of why women are dominating men in higher education:

- Girls’ stronger verbal abilities, which allow them to “settle down in school” earlier than boys (he says that boys tend to be stronger in numerical and spatial abilities), which contributes to their higher preparation for higher education;

- The fact that studies “for careers in which women tend to dominate, for example nursing and social work, has in recent years been incorporated into higher education;”

- The fact that “statistically, males are more likely to take up vocational qualifications, for example in plumbing and construction” for careers that pay well, making them less likely to apply to university.

Professor Smithers considers the inequity a problem, and calls for work at the primary level of education to help boys become better prepared for university. He makes specific reference to the insufficient number of STEM graduates in the UK:

“We need to go with the grain of what children are really like when they come to school. I think we need to accept that there are differences between the sexes and that currently our system favours girls. That’s a problem for boys in terms of their personal development but it’s also a problem on a national level. We don’t have enough people coming through in areas where men are traditionally strong – for example maths, physics and engineering – which in turn means we don’t have enough strong teachers in those subjects.”

Gap between women’s greater higher education performance and their workplace position

Mr Chamie notes that women’s greater participation and attainment in higher education has yet to translate into the world of paid work:

“Despite these educational gains, women continue to lag behind men in employment, income, business ownership, research and politics. This pattern of inequality suggests that societal expectations and cultural norms regarding the appropriate roles for men and women as well as inherent biological differences between the sexes are limiting the benefits of women’s educational advantage.”

Recent studies and books have also posited that women tend toward lower self-esteem and greater perfectionism, making them less assertive in the workplace. One popular and controversial book published recently is The Confidence Code: The Science and Art of Self-Assurance - What Women Should Know, by journalists Katty Kay and Claire Shipman. Ms Kay and Ms Shipman told The Atlantic Magazine that: “We watch our male colleagues take risks, while we hold back until we’re sure we are perfectly ready and perfectly qualified. The natural result of low confidence is inaction. When women hesitate because we aren’t sure, we hold ourselves back.” Ms Kay and Ms Shipman’s argument captivated some, and bothered others. The latter group contend that placing the blame on women’s arguably innate psychological and behavioural tendencies obscures the real problem of institutional barriers to women’s greater participation in the workplace.

Room for greater inclusion for all

Perhaps the right way to end this article is the opinion of Claudia Buchmann, co-author and sociology professor at Ohio State University, who told Times Higher Education that:

“We really need schools that set high expectations, that treat students as individuals – not just as gendered groups – and also motivate students to invest in their education so that they can reach the big returns of a college degree that exist in today’s labour market.”

Encouraging men to greater participation and attainment in higher education, and removing barriers for women to really realise the value of their education in the workplace, seems like a promising idea – and a sound one economically. In the meantime, it appears that important shifts in the relative participation rates of women and men are underway, no doubt with far-reaching implications for recruitment and student services in many world markets.