The link between employability and international student recruitment

As business leaders and prospective students increasingly seek proof of graduate readiness and success, it is no wonder that employability has emerged as a key issue for educators. But what exactly does the concept of “employability” entail and how does it relate to international student recruitment? In today’s post, we take a broader look at some current ideas and issues related to employability, and explore how a better understanding of students’ transition to the labour market can be a source of strategic advantage for education marketers.

Why employability is a key issue

In recent years, employers, policy makers, and other experts have been increasingly calling upon educators to deliver programmes that are relevant to students’ lives (and labour market demands). For some, that means an education that connects with students in authentic ways or that teaches the skills they’ll need to succeed in the workplace, such as critical thinking, communication, and creative problem solving. But there are also concerns that today’s education systems are not sufficiently preparing students to become the “innovative thinkers” and “engaged citizens” needed to meet the evolving demands of the 21st century economy. A recent Gallup study of US college graduates found that those who had worked on a long-term project (at least a semester), had an internship where they could apply skills, and were very engaged in an extracurricular activity were three times as likely to be engaged at work. However, only 6% of respondents “strongly agreed” that these three types of experiences had been part of their higher education studies. Furthermore, the study found that students who had felt their professors cared about them as individuals, had professors that made them want to learn, and had a mentor were three times more likely to thrive as those who did not feel supported. Yet, only 14% of respondents indicated that all three factors were part of their college experience. A recent blog post on KQED’s MindShift blog points out that:

“Feeling connected and mentored makes a difference, just as understanding how learning is relevant and applicable makes students feel prepared for life after college.”

Where students go after graduation

Two further studies offer some insights on students’ lives after college, and on the employment patterns and outcomes for UK and US graduates in particular.

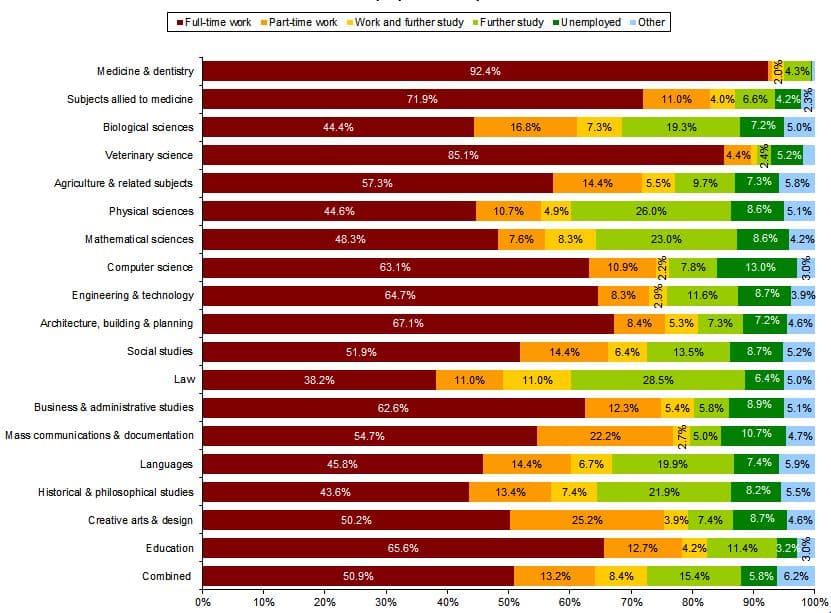

According to the 2012/13 Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education (DLHE) survey, 57.7% of UK “leavers” were engaged in full-time work approximately six months after completing their higher education. At that same point, 12.2% of grads were enrolled in further study and 6.2% were unemployed, as illustrated in the chart below.

- Over a third of graduates who studied law (39.5%) were pursuing further study, in keeping with the typical route to qualification in that profession;

- 92.4% of those who studied medicine and dentistry and 85.1% of those who studied veterinary science were employed full-time;

- Comparatively, those who studied computer science had the highest unemployment rate at 13%, followed by mass communications and documentation (10.7%), and business and administrative studies (8.9%).

More details by subject area are in the graph below.

“On average, graduates who had not enrolled after earning their bachelor’s degree were employed for about 84% of the months that elapsed between their graduation in 2007/08 and the second follow-up study in 2012.”

But although some graduates are making the transfer to the workforce, unemployment continues to be an issue for many worldwide, and for youth in particular.

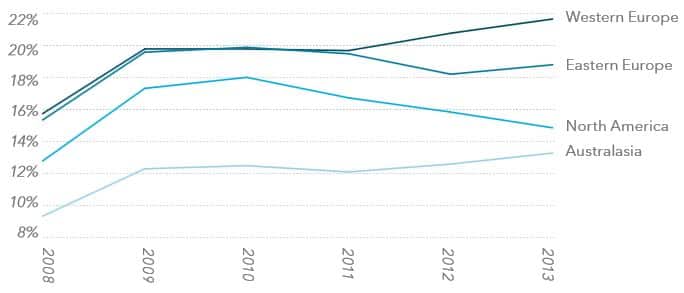

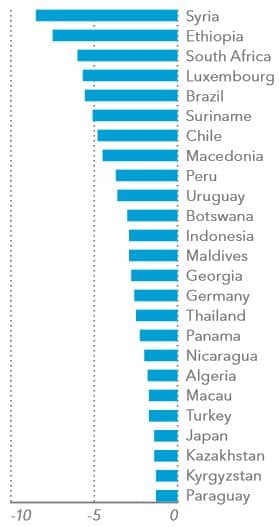

As reported by Euromonitor International, young people aged 15-24 have been negatively affected by unemployment in most countries since the start of the 2008 global economic downturn. In 2013, Western Europe had the highest average youth unemployment rate – among major global regions – at 21.7% of the economically active population:

How employability relates to recruitment

So what does this all mean for international student recruiters? According to Scott Vasey, Director of the International Students Preparatory Academy (ISPA), paying attention to global labour markets can provide recruiters with a strategic advantage:

“As an international recruiter, if you are aware of growing needs in foreign countries, you can tailor your pitch to meet a specific market. And that can be the difference between signing students up for your school or merely sparking a passing interest.”

As Mr Vasey notes, in a global economy, demand in one area of the world can lead to supply elsewhere. Furthermore, as the market becomes crowded with prospective candidates, it can become harder for employers to “ascertain who is actually qualified.” Graduates need to differentiate themselves from the competition, and one way they can stand out is by studying abroad. He adds:

“Demonstrating to prospective students the very specific ways that attending your school will help them in the future, and showing a knowledge of their country’s economic climate, will do more to attract them than the prettiest pictures of an oak-filled campus ever will.”

This notion is echoed in a recent report from the European Commission, Modernisation of Higher Education in Europe: Access, Retention and Employability 2014. It suggests that employability not only depends on the quality of education graduates receive during their studies, but also on changes in the general state of the economy and the labour market, which are “the most important determinants of job opportunities.”

Defining and measuring employability outcomes

We’ll close by turning our attention to some of the other insights from the European Commission report, and explore how educators can define, measure, and monitor outcomes with respect to employability. Employability plays a central role in the European Commission’s higher education reform strategy, and a variety of national practices aim to enhance graduates’ employability and ease their transition to the labour market. But although there are “various conceptualisations of employability,” the report identifies two main types of definitions:

“Employment-centred approaches focus directly on graduates’ employment prospects: higher education institutions are responsible for preparing graduates for employment. In these cases, higher ed institutions are often evaluated based on graduate employment rates... Competences-centred approaches, on the other hand, refer to the responsibility of higher ed institutions to develop the skills and competences of graduates necessary to find a job. Worth noting, however, that employment-centred and competences-centred approaches are not contradictory and often exist in parallel.”

When it comes to evaluating the performance of higher education institutions in these respects, the majority of systems looked at in the report require higher education institutions to submit employability-related information (e.g., as part of quality assurance monitoring or other data gathering processes). For example, higher education institutions in some countries can be required to:

- show that their programmes are relevant for the labour market, answering an existing demand;

- provide proof that they involved employers or included their perspectives in programme development;

- regularly submit data on the employment of their graduates, or prove that they have a monitoring system in place; and/or

- demonstrate that they have student services that can provide support for the labour market transition of graduates.

For additional insights on competency-based learning see our article, "Is employer engagement in education the next source of competitive advantage?" The report notes as well that employers participate in external quality assurance processes in around half of the education systems studied. While “evaluating the impact of existing measures is not straightforward,” the report notes that conducting graduate surveys at the national and regional level can be an effective means of measuring employability outcomes, as can employers’ surveys, which have been conducted in many European countries. With regard to the value of these initiatives, the report adds:

“One prominent goal of setting up such evaluation processes is to make employability-related information on higher education study programmes public. This can inform current and future students on their potential career prospects.”

European countries, however, usually discuss employability-related concerns from the perspective of higher education institutions, or the student population as a whole, without concentrating on specific groups of students:

“It is therefore impossible to know whether factors such as socio-economic disadvantage or ethnicity – which are known to have an impact on access and completion of higher education – may also have an impact on employment after graduation.”

This suggests there is a need to both extend the data gathering efforts in many systems but also to widen the participation agenda to address retention issues, as well as employability policies and practice. For more articles on employability and labour gaps within the context of individual markets, such as Nigeria, Brazil, France, Vietnam, and other countries, please review our archives of related ICEF Monitor posts.