What about the 20 million students who didn’t study abroad last year?

- A new analysis points out that for every student who is able to travel internationally to study, there are many more who would like to study abroad but are unable to do so

- A rapidly expanding field of ed tech partnerships and investments is opening up new opportunities for educators to reach that larger student pool

Education technology has played a massive role in programme delivery since the start of the pandemic. And COVID has unquestionably amplified the scale and pace of adoption for new online learning tools, the development or adaptation of education programmes for remote learning, and even the emergence of new transnational delivery models.

The question now is: which of those new tools and practices will "stick" after the pandemic? Put another way, how much of what we're seeing now is simply a response to the current crisis (and is likely to fade away after international student mobility resumes on a larger scale)? And which aspects represent a real shift in the global education market in terms of how teaching and learning happens across borders?

It is far too early to have clear answers to these questions. Even so, the experience of the last year has taught us some important lessons and educators, governments, investors, and other stakeholders have begun to place their bets as to how the international marketplace will continue to develop in the years ahead.

"COVID-19 is expected to have a lasting impact on patterns of consumption," says HolonIQ Co-CEO Maria Spies. "Not just in terms of the learners themselves but also in the way that [international educators] respond and also in the actions of governments."

Speaking at a recent webinar offered by HolonIQ, a market intelligence platform for the global education market, Ms Spies set out a high-level model of the global education market.

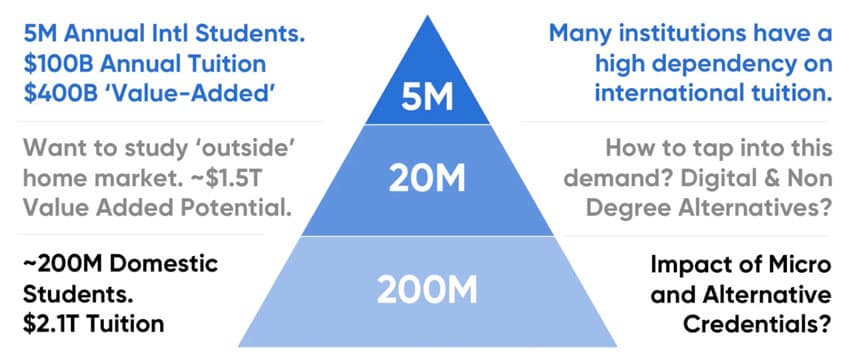

The most visible part of the international market is the roughly five million students who travel abroad for post-secondary studies. (We should add to that another couple of million students engaged in language travel, and hundreds of thousands more in the secondary and non-award sectors.)

But, as the following chart illustrates, HolonIQ estimates that for every student who goes abroad, there are another four – and an estimated global total of 20 million higher education students – who would like to study outside their home countries but are unable to do so. This may be because of family or career commitments or because they lack the qualifications or funds to support studies abroad.

Whatever the case, the point is that, seen through this lens, the "addressable market" for international education is clearly much larger than just those students who can travel overseas. We might also conclude that the pandemic has taught us that education technology is opening up new opportunities for educators to reach and teach that larger student pool.

To illustrate, Ms Spies cited the example of Coursera, where 62 million of the MOOC platform's total base of 77 million students are based outside of the United States. That works out to, "25 times the [foreign enrolment] of the top four English-speaking destination countries" combined, she explained. As we noted recently, Coursera has otherwise reported that 51% of its 2020 revenue came from foreign students.

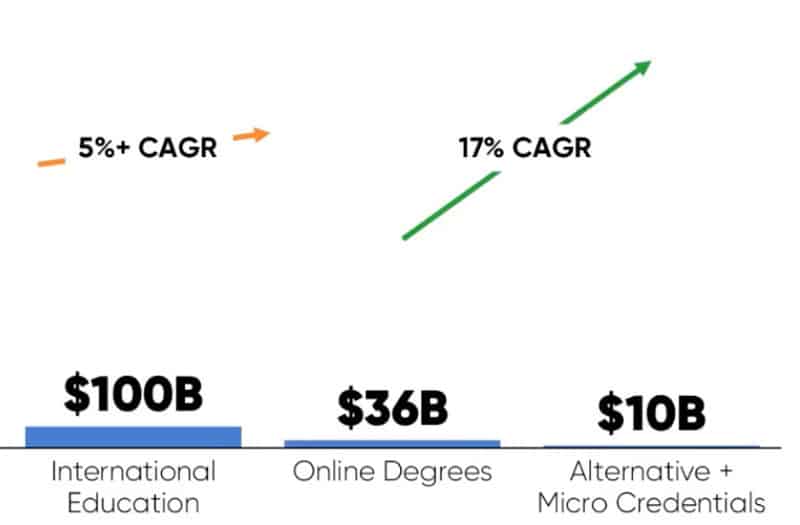

More broadly, HolonIQ's analysis compares the relative growth rates of international education with that of degrees and other credentials delivered online. Not surprisingly, while the economic value of internationally mobile students is much larger, the annual rate of growth is relatively modest (5%) whereas online learning, starting from a much lower base, is growing roughly four times faster.

What this all means for the moment is that educators of all stripes are finding new ways to incorporate remote learning. For most, this was of course triggered by the need to pivot to online in the early stages of the pandemic. But the months since have seen new levels of investment and partnership between institutions, schools, and edtech providers.

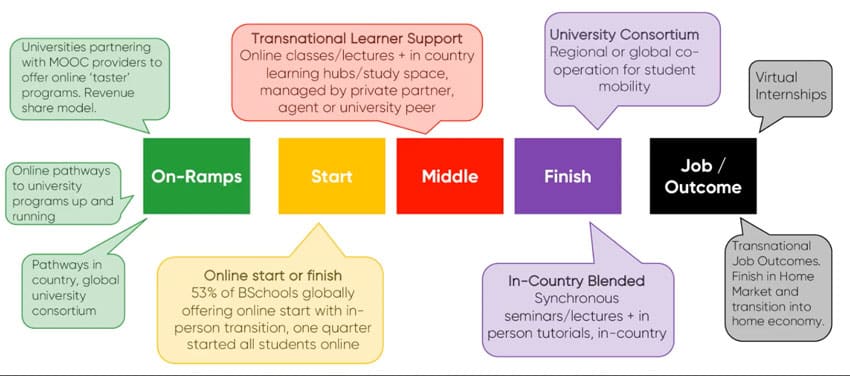

In mapping the space, HolonIQ differentiates between "on ramps", which provide preparatory or sampling options for students abroad and between other remote learning models that are targeted across all phases of a programme of study. These include blended and hybrid delivery as well as programme models where students begin their studies online and then transition to in-person learning.

The overview we see below is framed largely around degree studies, but we can imagine an even more varied landscape for remote learning that incorporates the burgeoning field of alternate and micro credentials.

And so we come back to the question of how the practice – or even the concept – of international education may change after this intensive period of experimentation, investment, and, for many, newfound first-hand experience in larger scale remote learning. Most international educators consider, and quite rightly, that the in-person, cross-cultural experience is an essential element of what they do. But what we see in the HolonIQ analysis is an invitation for many institutions and schools to now consider incorporating or expanding complementary remote programmes to reach a wider base of students abroad.

For additional background, please see: