Malaysian government cools on study abroad but outbound still growing

Speaking recently at an event at Mahsa University, Higher Education Minister Datuk Seri Idris Jusoh made the case for Malaysian students to pursue their degrees at home. The Minister cited the improving standard of higher education in Malaysia as well as the declining value of the Malaysian ringgit, a trend that has effectively made study abroad more expensive for Malaysian students and families. This is indeed the case as the ringgit has had a rough passage over most of 2015 and 2016. Malaysia is an oil-exporting country and the collapse in world oil prices set the ringgit on a downward trend starting in 2015. Bloomberg pointed out recently that the Malaysian currency was the worst performer among 11 major Asian currencies over the past six months, and that it lost nearly 5% of its value during that period. Even so, the ringgit appears to have entered into a period of relative stability over the latter part of 2016 and early months of 2017. Capital markets are showing renewed interest in the currency, a development that foreshadows an improved economic and trading outlook ahead. In fact, some analysts now project that the ringgit will be among Asia’s better-performing currencies through 2017. “The ringgit has a few things going for it now,” Prashant Singh, a portfolio manager with the investment firm Neuberger Berman said in a recent interview. “If you look at the overall balance of payments, with the increase in commodity prices, the current account has improved. Foreign direct investment in Malaysia has improved so that has helped.” All things considered, that improving outlook for the economy is likely to ease affordability concerns for students and parents, and to deduce any dampening effect on outbound mobility arising from the weaker ringgit over the last two years.

Climbing the ladder

Turning to the question of higher education provision, Minister Idris also noted, “There are no reasons why we should be sending our students abroad when we have five top research universities here including Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Universiti Sains Malaysia and Universiti Malaya…When we send our students abroad, they are also not placed in top universities in the world. So why should we spend four times the amount when we can get them to study locally?”

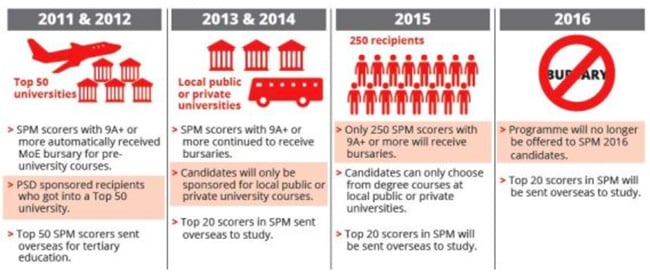

The Minister’s remarks reflect the perspective of a government that has pulled back on scholarships for study abroad in recent years. The number of prestigious Public Service Department (PSD) scholarships - awards given to the top-performing students in the country - has declined sharply since 2013. Some scholarships remain available for those with the best scores on the Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia examination. The SPM, also known as the Malaysian Certificate of Education, is a national exam taken by all fifth-year Malaysian secondary students. It is roughly equivalent to the O-Level in the British system, or Grade 11 in the US K-12 system.

As the following chart reflects, the PSD scholarship programme has shifted sharply since 2013, with a much greater focus on awards for domestic study and a reduced number of scholarships for higher education abroad.

The drive to go out

Malaysia’s emphasis on local provision harks back to late 1990s when the government liberalised the higher education system, sparking a considerable expansion of private post-secondary education but also significant growth in the number of foreign providers active in the country. In the wake of those important policy changes, the number of private institutions in Malaysia increased from six in 2001 to more than 400 by 2013, while the number of international branch campuses in the country grew from three to nine over the same period. Further to those branch campuses, a number of foreign providers also partnered with Malaysian institutions during those years to offer joint programmes, and often leading to degree completion options abroad. And in 2015, Malaysia released a ten-year blueprint for its higher education system. The plan reinforces the country’s commitment to becoming an important hub for higher education in the region, and its ambition to host growing numbers of foreign students. But in the midst of all of these important developments, the number of outbound students from Malaysia has also continued to grow. Long an important sending market, Malaysia was among the top ten senders globally until the late 1990s when it was overtaken by other major markets, notably China, India, and South Korea. The country had fallen off the top ten global senders list by 2005 but it remains an important source market nonetheless and has in fact continued to grow over the past decade. Nearly 47,400 Malaysian students went abroad for higher education in 2005, and that outbound count expanded to just under 65,000 students by 2015. Roughly six in ten go to the UK, Australia, or the US, but Malaysian enrolment overseas is pretty widely distributed outside of those top three destinations, with host countries in Africa (Egypt), the Middle East (Jordan), Europe (Russia, Ireland, France, Germany), and Asia (India, Japan) rounding out the top ten study destinations. The UK has enjoyed an upward trend in Malaysian enrolment since 2010. Roughly 13,800 students went to the UK that year, and Malaysia is now the second-ranked non-EU sending market for UK education, after only China, with just over 17,400 students enrolled in 2015/16. UNESCO indicates that Australia’s numbers have slipped over the same period, from a high of 20,500 students in 2010 to 15,400 in 2015. However, the latest numbers from the Australian government suggest that UNESCO may be undercounting Malaysian enrolment in the country. In fact, the Australian Department of Education and Training highlights Malaysia as one of Australia’s fastest-growing markets for 2016, with year-over-year growth of 18%. With only modest growth over the past decade, Malaysia is the 22nd largest sending market for the US. But Malaysian student numbers in the US have grown for nine years in a row, albeit modestly in some years, and have shown stronger growth over the last two years, increasing by 6% and 8% in 2014/15 and 2015/16 respectively. As these leading destination trends reflect, there is still considerable strength in the Malaysian outbound market, a pattern that may well now be extended as the country’s economy and currency continue to strengthen in 2017. For additional background, please see: