Market Snapshot: Slovakia

With so many recent changes and reforms to Slovakia’s primary, secondary, and tertiary education systems, the government’s demonstrated willingness to learn from other jurisdictions, and a strong and steady history of outbound mobility, opportunities exist for deepening educational links in this corner of Central Europe.

Country background

Tucked behind the Cold War’s Iron Curtain from 1946 to 1989 as part of the Czechoslovak Republic, and comprising one-half of Czechoslovakia following the 1989 Velvet Revolution, Slovakia became an independent republic in 1993. Slovakia today is a parliamentary democracy with a president as head of state. Slovakia became a member of the European Union in 2004. The country is divided into eight administrative regions, with Bratislava as the capital and most important city.

Slovakia’s education system

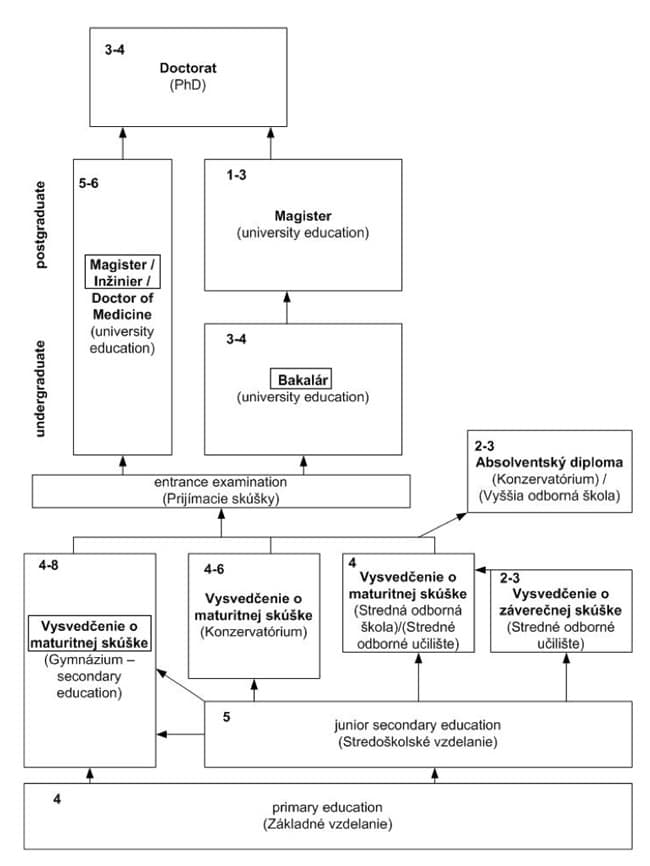

The period for compulsory school attendance in Slovakia is set at ten years and begins at the age of six, and the academic year runs from September to August. The OECD estimates primary school enrolment at 427,000 students and secondary enrolment at 227,000 students as of 2013. The following chart provides an overview of the entire system.

Concerns about outcomes

The Slovak Chamber of Teachers has raised concerns that fundamental changes in education are made too often. The Ministry of Education, aware of perceived policy gaps, recently established the Educational Policy Institute (EPI) to draw policy best practices from other countries and to provide advice to the government on strategic policy decisions. A further OECD report from 2014 highlights concerns about a correlation between student socio-economic status and student performance. Students from rural areas have also been found to significantly underperform their peers in larger cities. In line with the Millennium programme, full cohort national assessments in mathematics and Slovak language and literature were introduced for Year 9 students in 2009. Initiatives to develop key competencies for teachers, part of a commitment to developing higher teacher standards, were introduced in 2006 and updates piloted in 2013. Overall, support for the observation and improvement of classroom practices is broadly accepted among education stakeholders.

Higher education in Slovakia

Slovakia introduced a new Higher Education Act in 2002. Among other things, the new Act laid out conditions determining the legal status of higher education institutions, fields of study, academic titles, evaluations and accreditation. Recent amendments have aimed to raise the standard of higher education and higher education institutions. Higher education institutions in Slovakia are classified by the nature and scope of their activities into university-type and non-university type HEIs. University-type institutions provide education in study programmes at the bachelor, master, and doctoral levels. Currently, there are 20 state universities and six recognised private higher education institutions operating in the country. There are also two military and four theological institutions. Accreditation is carried out by a special accreditation commission, the Akreditačná komisia. The commission determines whether individual institutions may or may not be categorised as universities and whether private institutions are eligible for state recognition. The commission’s evaluations and recommendations are presented to the ministry for approval. According to a Study in Slovakia booklet prepared by the Ministry of Education, foreign higher education institutions based elsewhere in the European Union, the European Economic Area, or Switzerland may provide higher education programmes in Slovakia once they have been granted official approval by the ministry.

Expanding options for international students

In 2013, 11,102 international students studied at the tertiary level in Slovakia, comprising 6% of the total postsecondary population. The largest numbers arrive from the neighbouring Czech Republic. Of these, approximately 45% study at the undergraduate level and the remainder at the graduate and postgraduate level, according to figures provided by Institute of Information and Prognoses of Education. Comenius University hosts the largest number of international students of any public Slovak university, welcoming 2,348 foreign students in 2013.

At the tertiary level, the main language of instruction is Slovak. However, a number of programmes are delivered in English, with plans to expand these in the coming years. Limited programmes are also offered in German, Italian, Russian, and French.

As part of the Bologna process, the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) was introduced in 2002 for all levels and forms of higher education study. Full time study at state and public higher education institutions is available free of charge for citizens of the Slovak Republic. Nationals of the European Union, European Economic Area, and Switzerland do not pay a tuition fee if they study a programme offered in the Slovak language. For other foreign students, the tuition fees for study programmes at any level apply and are set by each institution.

Steady outbound

According to the latest UNESCO statistics, 33,127 Slovak students studied outside the country at the postsecondary level. The top destinations for tertiary level students from Slovakia include:

- Czech Republic (24,819);

- Hungary (2,172);

- UK (1,425);

- Austria (1,260);

- Germany (884).

As well, more than 3,000 Slovak students were estimated to have studied English abroad in 2011.

Recent trends and issues

Other OECD researchers have flagged ongoing concerns with labour market outcomes among Slovakia’s higher education graduates. Youth unemployment in Slovakia - which was pegged at 33% in 2011 - is the third-highest in the OECD and is among the highest in the EU, a trend the report links in part to a mismatch between graduate skills and current labour market needs. The country’s Roma population and those living in remote regions face even greater barriers to employment. A February article in the Slovak Spectator echoed the concern with weak school-to-work transition among Slovak’s young people. The article highlights findings of a survey published by the Education Ministry that found that 46% of university graduates have never worked in the field in which they studied. Furthermore, the data also suggests that a major gap exists between the salaries of those trained in technical fields as opposed to the humanities. Education Minister Juraj Draxler suggests the ministry is willing to adopt changes in the university system to help students select the best school for their further studies and to improve their chances of future employment.

“It simply does not make any sense to finance something from which it is extremely difficult to find a job,” the minister said, as quoted by the TASR news service.

The article also points to concerns over funding. According to Viktor Smieško, chairman of the Council of Universities, higher education institutions are funded based on overall student numbers, which encourages institutions to take on students who may not be adequately qualified. Instead, he suggested financing should be tied to internationally accepted standards and outcomes. The state should also clearly mark its elite universities and fund these accordingly, he said.

An untapped partner?

Slovakia’s commitment to the Bologna Process and its focus on expanding English-language programmes to better attract and serve international students within its borders speaks to a broader opening up of internationalisation efforts within the country, a trend that appears set to continue in the years ahead.