Forecasts point to strong growth in outbound mobility for Pakistan

Pakistan, the sixth most-populous nation on Earth, is predicted to see its population grow to nearly 300 million people by mid-century. Despite a very low current ratio of 17-to-23-year-olds active in higher education (only 5.1%), demand for higher education is growing in the country and so is demand for study abroad. The British Council attributes rising interest in higher education to an increase in GDP per capita, and its report, Postgraduate Student Mobility Trends to 2024, clearly illustrates why Pakistani outbound student mobility is set to reach new levels. According to the report, in Pakistan:

- The tertiary-aged population will grow 0.2% annually between 2014 and 2024;

- Annual growth in tertiary outbound mobility at the postgraduate level will average 6.4% - a rate behind only that of Nigeria (8.3%) and Indonesia (7.2%) among the countries covered in the report.

The large gap between these two growth forecasts underlines Pakistan’s promise as an outbound market.

Fast facts

Some additional background on Pakistan:

- More than 300 languages and dialects are spoken, including Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, and Pashtu, but English is the official language and the language of higher education.

- Male literacy is 70.2%; female literacy is 46.3%.

- There are 136 universities, more than 3,000 technical and vocational schools, and numerous free religious schools (known as madrassas).

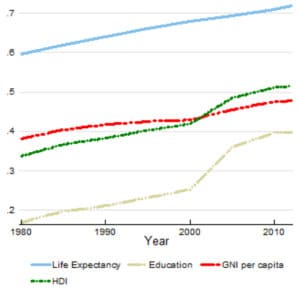

- According to the UN’s 2013 Development Report, expected years of schooling have doubled since 1980.

The following chart from the United Nations Development Programme shows the rapid rise of four key development indicators over the past three decades, and illustrates as well the growing capacity of Pakistani students to pursue study abroad.

Mobility patterns set to change

UNESCO data for 2012 shows that the top ten study abroad destination countries for Pakistani students, in order of popularity, are the UK, the US, Australia, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Sweden, Malaysia, Germany, and Kyrgyzstan. But Pakistani mobility patterns are set to shift in the next ten years. According to the British Council, the top destinations for Pakistani postgraduates by the year 2024 will be Australia (a predicted 7,400 students), Germany (6,000 students), and the UK (5,000 students). Looking at year-over-year growth forecasts in percentage terms reveals that Australia (+10.6%), Canada (+9.9%), Germany (+9.6%), and the US (+5.4%) are expected to register the largest increases. The British Council notes the forecast trend toward other destinations overtaking the UK, but doesn’t attempt to explain it. Reports elsewhere suggest that new immigration rules, fee hikes, and a growing perception of Britain as unwelcoming toward foreign students, are the main factors.

Education reform and the constitution

Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif says his government’s goal is to develop an education system compatible with the needs of a knowledge-based economy, specifically in the areas of science and technology. He also has called for modernising the education system, and focusing on female education. “For Pakistan,” he says, “education is not merely a matter of priority, but it is the future of Pakistan, which lies in its educated youth.” Prime Minister Sharif has described education as a national emergency. “More than half of the country’s population is below 25 years of age. With proper education and training, this huge reservoir of human capital can offer us an edge in the race for growth and prosperity in the age of globalisation. Without education, this resource can turn into a burden.” Muhammad Baligh Ur Rehman, Minister for Education, Training, and Standards in Higher Education, has echoed the Prime Minister, saying that the government needs to enhance literacy and promote quality higher education. He says such initiatives are needed to ensure progress for Pakistan. Previous governments had talked of enacting education reform, but reformists were blocked by the autonomy clause in the 18th Amendment to the Pakistani constitution. The amendment, passed in 2010, gave provinces the power to make educational decisions. However, Pakistan’s top court stated in 2011 that the federal government retains responsibility over education, despite the 18th Amendment. In the wake of this ruling, the government set up the National Curriculum Council (NCC) in 2014 to create a uniform national syllabus. However, the federal and provincial governments failed to develop a consensus on exactly how the NCC would function. And during a mid-2014 meeting of provincial education ministers, the provinces of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh expressed resistance to any loss of local authority. The 18th Amendment was passed to remove the sweeping, non-democratic powers accumulated by military presidents General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq and General Pervez Musharraf, and to repair multiple infringements to the Constitution. Reluctance to change part of the Amendment a mere four years after it was ratified to democratise the country is understandable. But when education ministers met just last month for the latest Interprovincial Education Ministers’ Conference, they finally emerged with a policy. The agreement will affect not only curriculum, but will create textbook boards, teacher training institutes, and examination assessment boards. All of this is slated to launch from January 2016; however, it should be noted that the policy came about with limited support from Punjab, Balochistan, and Sindh provinces. How that affects the agreement moving forward remains to be seen.

Money troubles

Any education initiatives hinge upon funding, and this is where Pakistan is at a severe disadvantage. A recent report by Britain’s International Development Committee found that only 768,000 Pakistanis paid income tax in 2012 - 0.57% of the population. The figure is about 15% in countries with comparable levels of development. In addition, the report revealed that 69% of National Assembly members and 63% of Senate members paid no tax in 2011. These embarrassing facts have begun to create external political problems for Pakistan. For example, in Britain there have been calls to link any increases in bilateral aid to better efforts to enforce tax laws, but as yet there are no major plans afoot to tackle these problems.

Security worries

Security remains a pressing concern in Pakistan, and the country is the eighth most dangerous in the world, at least in the estimation of one US think tank. While large cities such as Karachi and Lahore are on the safer side, in rural regions the central government’s influence and power wanes and militant forces operate openly. Security risks in those outlying areas directly affect the provincial education sector. Attacks on schools, mosques, and other public sites occur regularly. The most infamous example is the December 2014 Taliban attack against a school in Peshawar that left 145 people, mostly schoolchildren, dead. In an effort to discourage Western-style education, the Taliban have targeted English-language schools, threatened owners and students, and distributed anti-Western leaflets. The Taliban are specifically dedicated to restricting access to education for girls. The case of 14-year-old Malala Yousafzai, who was shot in the head for advocating girls’ education, made international news in 2012. Again in December 2014 two bomb blasts struck a girls’ college in Khyber Province. This was one day after the deadly Peshawar attack. No injuries occurred in the explosions, but the message was clear. In Pakistan’s tribal regions, US drone strikes have also done their part to disrupt education. A New York Times article revealed that, under US policy, any gathering of “military age males” is officially considered to be a gathering of militants. This is a significant safety issue, and several schools have suffered drone attacks. While suspected militants have been killed, it has come at the cost of hundreds of civilian lives. Needless to say, foreign educators cannot safely venture into rural areas. To connect with students they must rely on local agents, or attend education fairs in the cities, such as the International Education Exhibition of Pakistan, set for Karachi in April 2015, or the PFL Education Fair, taking place in Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad in March. Such events attract thousands of students and their families from around the country.

International help is abundant

The international community maintains a strong and steady presence in the Pakistani education sector. The World Bank’s Tertiary Education Support Project, UNICEF, and numerous other bodies are making substantial investments to strengthen the country’s education system. USAID hopes to provide 21,000 higher education scholarships by 2018, and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) aims to train 90,000 teachers and build 20,000 classrooms through the end of 2015. Pakistan continues to face a number of challenges as it continues to work to improve its education system and governance. There are few political issues that unite Pakistan like that of education, however, and this consensus and the political focus on education is unlikely to change no matter the obstacles to continuing progress or the political winds of the day.

Most Recent

-

British Council says student recruitment to UK higher education will get a boost this year from South Asia and the “Trump effect” Read More

-

New Zealand expands post-study work opportunities for international students Read More

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More