Market Snapshot: Mexico

Mexico is first and foremost a Latin American nation, yet it is also geographically part of North America and its efforts to build student mobility initiatives have recently focused on its continental neighbours, the US and Canada. In addition, it has looked toward English-speaking countries overseas for a mobility boost. Today ICEF Monitor examines Mexico’s renewed focus on English-speaking countries, and gives an overview of other mobility-related developments.

Middle class expansion slows amid cautious economic outlook

Mexico’s middle class has grown in recent years, and as a result household investment in education has increased by approximately 43% between 2002 and 2011. Mexico is expected to number in the world’s top 20 countries for overall higher education enrolment by 2035, which means families’ ability and willingness to send their children abroad for schooling – already increasing – will likely follow the same path. Some more quick facts about Mexico include:

- 70 million Mexicans are now considered middle class.

- Mexico’s GDP per capita as of 2013 was US$10,600, which places it 66th in the CIA’s World Factbook rankings.

- Mexico spends 5.2% of GDP on public education, which puts it close to the Latin American and OECD averages.

- Mexico sends approximately 26,866 tertiary-level students abroad according to UNESCO (2012 data); other sources put the number closer to 30,000.

- According to the Washington Post, as of 2012 Mexico was graduating 130,000 engineers and technicians a year from universities and specialised high schools - more than Canada, Germany, or Brazil.

- Total university enrolment has tripled in 30 years to almost three million students.

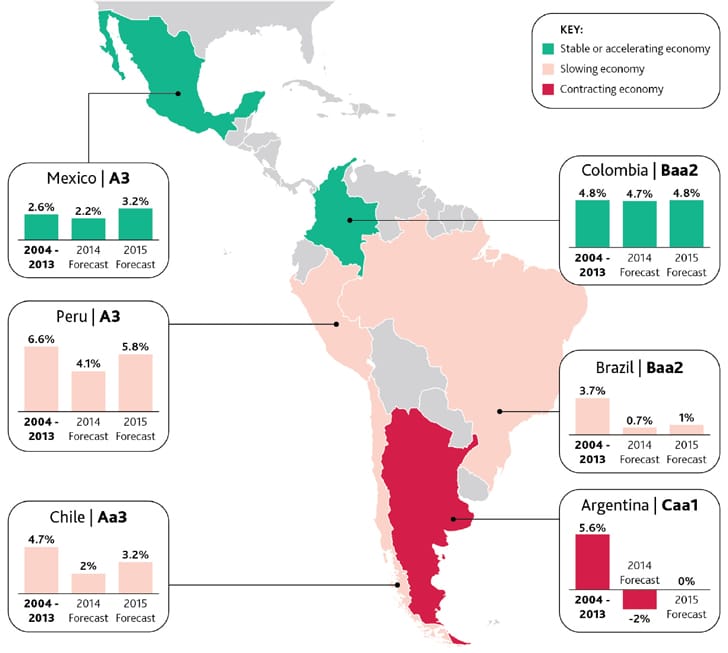

Despite a growing middle class and more family expenditure on education, the Mexican economy is still seen as under-performing. Yet experts believe it is the only country in Latin America, other than Colombia, where economic growth in 2015 will reach its historical average.

Conversely, rumbles from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru suggest that middle class expansion in many Latin markets may be reaching its limit, at least for the moment. As the following chart illustrates, economic growth is expected to slow in many major regional markets this year.

Mexico and the US

Education linkages between Mexico and the US are growing stronger, a fitting trend given their highly interconnected economies (Mexico is second only to Canada as an export market for the US and is its third-largest trading partner after Canada and China). In 2013, President Barack Obama announced a programme called 100,000 Strong in the Americas that seeks to “more than double the number of exchange students in the Americas in less than ten years.” This programme will boost Mexico’s own initiative, Proyecta 100,000, launched by Peña Nieto’s government and designed to have 100,000 Mexican students enrolled at US universities by 2018, and 50,000 US students enrolled at Mexican institutions. Initiatives like these are timely for Mexico. The country was once a top destination for US students, with numbers reaching their highest level (about 10,000) during 2005/06. But that was before the Mexican government under then-President Felipe Calderón launched a war against drug traffickers, spurring violence that has killed at least 60,000 people and prompted the US State Department to routinely issue travel warnings. As a result of the chaos, the number of US students enrolled in Mexico plummeted to a 16-year low of about 3,700 during the 2012/13 school year. This is a particularly anemic total when one considers that Mexico - a bordering nation - did not rank among the top ten study destinations for American students last year and was outdrawn by countries such as Poland and India. However, all the cross-border mobility problems can’t be laid at Mexico’s doorstep. On the US side as well, barriers have arisen in recent years. Most notably, visa policies changed after 11 September 2001. Mexican students now must acquire visas to visit the US, whereas in the past they were able to more easily travel north for research trips, seminars, and education conferences. But even though Mexico-to-US mobility is not as direct a path as it once was, during the 2013/14 academic year 14,779 Mexican students attended US colleges and universities, up 4.1% from the previous year. According to the US Commerce Department, that number represented an influx of US$473 million for the US economy. With new mobility initiatives in place on both sides of the border, this number will no doubt increase in the years ahead.

President Peña Nieto has been explicit: his plan is to turn Mexico into the second or third largest source of foreign university students in the US, after China and India. With approximately 54% of US-bound Mexican students seeking their first degree, and 40% studying business and engineering, stateside educational institutions with strong business and engineering programmes looking to bolster enrolments will be well positioned to benefit from recent Mexican/US bilateral efforts.

Mexico and other English-speaking countries

Mexico’s other northern neighbour, Canada, has also been the focus of recent mobility initiatives. In September, the Mexican government announced it would enhance scholarships for Canadian graduate students and post-doctoral researchers by providing international travel to and from Mexico. Also in September, the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada renewed its memorandum of understanding with Mexico’s National Association of Universities and Institutions (ANUIES). The new five-year agreement expands Canada-Mexico tertiary cooperation in information exchange, joint events, internationalisation, and the promotion of two-way student mobility. This follows on the heels of other agreements to ease air travel restrictions between the two countries, and to speed the processing of study permits for Mexican students, with the goal of producing a nearly 100% approval rate for students who enrol at participating Canadian educational institutions. On the UK front, the governments of Mexico and the United Kingdom have declared 2015 “The Year of Mexico in the United Kingdom” and “The Year of the United Kingdom in Mexico.” The idea is to promote further bilateral exchange and cooperation, and the Mexican government is planning exhibitions, seminars, workshops, and joint research projects in the UK during the year. Separate from that agreement, but indicative of the tightening links between the two nations, a memorandum was signed at Mexico’s National Palace in the presence of President Peña Nieto and the Prince of Wales that for the first time mutually recognises and accredits academic studies between both countries. The pact could help up to 170,000 British and Mexican students to use their qualifications to extend their studies, undertake academic research, or obtain graduate level employment. The deal also allows scientists, technicians, and managers to fill skills gaps in both countries in important areas of the economy such as healthcare, the environment, and energy. The energy sector in particular is slated for structural change, and British graduates in those fields will be sought after to help Mexico make the transition. Both countries will also develop new grants and awards and work to bolster quality assurance. At the moment, the UK is the fifth most popular destination for Mexican tertiary-level students. While that lags far behind the US, the UK has one useful advantage: it is chosen by Latin Americans more typically because the country is considered an attractive place to study - suggesting Mexico may present opportunities for a wider field of UK institutions - while the US is often chosen due to the reputation of individual institutions. Looking across the opposite ocean, Mexico and Australia also have strong and growing economic links. Mexico was Australia’s largest trading partner in Latin America in 2013, with two-way trade valued at US$2.5 billion. The two nations already have a memorandum of understanding on education, research, and training that dates from November 2008, and today Mexico is Australia’s fourth largest education and training market in Latin America. The demand in Mexico for Australian education and training services is growing. Australian schools hosted approximately 2,000 Mexican students in 2013, most of them in tertiary institutions, and observers in Australia’s Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector are seeing increased demand for learning designed to improve productivity and skills.

Mexico’s challenges

President Peña Nieto has spoken of a shift on drug policies, but few observers have seen a difference from Calderón’s approach. Sky-high crime rates have dropped slightly, but high-profile killings – particularly of 43 student-teachers in the town of Iguala in September – have weakened Peña Nieto’s credibility and damaged Mexico’s reputation globally. The crime rate at home has influenced Mexican attitudes toward outbound mobility, notably in that a destination’s safety profile has risen in importance. According to a 2013 Guardian article that cites a body of British Council research, on a list of reasons Mexican students chose the UK as a study destination, safety rose from being 17th most important factor in 2007 to fifth in 2012. Those concerns are echoed by Pew Research Center data, in which crime is the number one worry for Mexican citizens. Also of note in the same survey is education slotting ninth on the list of concerns, with 52% of people saying poor quality schools are a “very big problem.” This is an improved result from 2013, when 63% of people were deeply concerned about schools, however the high figure suggests just how receptive Mexican students and families can be toward higher-quality options abroad. President Peña Nieto’s structural reforms to the education sector have enjoyed support from Mexico’s two leading opposition parties, but there are questions as to whether such cooperation can last. The president’s popularity is in freefall, with only 39% of voters registering approval in a recent survey by Grupo Reforma – an 11% drop since the first half of 2014. Part of this erosion of confidence has to do with perceptions of cronyism by the president and official corruption in southern Mexico related to the drug trade. In any case, President Nieto finds himself at a crossroads – public trust is breaking down right at the moment he had hoped to rally support for his programmes, and stability will be the key to any future progress on the government’s agenda.