The substitution effect of transnational education on international student mobility

Transnational education (TNE) is defined by UNESCO as “all types of higher education study programmes or set of courses of study, or educational services… in which the learners are located in a country different from the one where the awarding institution is based.” This includes, but is not limited to, the following most common types of TNE:

- Franchising - This is where the “home’” awarding institution licenses an offshore partner institution to deliver its programme(s) overseas. This type of TNE arrangement represents the larger share of the TNE market.

- Validation - In which the awarding institution validates an existing programme of an offshore education provider. This occurs either because the offshore institution lacks degree-awarding powers and/or as an effort to diversify in the local market.

- Articulation/twinning - In these cases, a “home” university and an offshore education provider, both having awarding powers, agree on allowing their students to enter each other’s programmes at an advanced stage. One example is the top-up bachelor options that are known as “2+1” or “2+2” programmes (two years in the offshore institution, one or two years in the “home” university).

- Joint and dual degrees - Where a “home” and an offshore university collaborate so that their students attend one mutually developed programme which leads to a joint degree or two separate degrees, one from each institution.

- Flexible and distributed learning - In these cases, a “home” institution provides its programmes through online or distance learning delivery, thus the physical presence of the student at the home campus is not compulsory. There are variations as to how this model is supported locally.

- Physical presence and corporate involvement – This is where a “home” institution develops a branch campus in an offshore location, and the degrees are awarded in the context of the “home” higher education system. (There are some cases where the branch campus operates as a university and the degrees are awarded in the context of the offshore higher education system. In this case, technically, it does not fall in the TNE categorisation.)

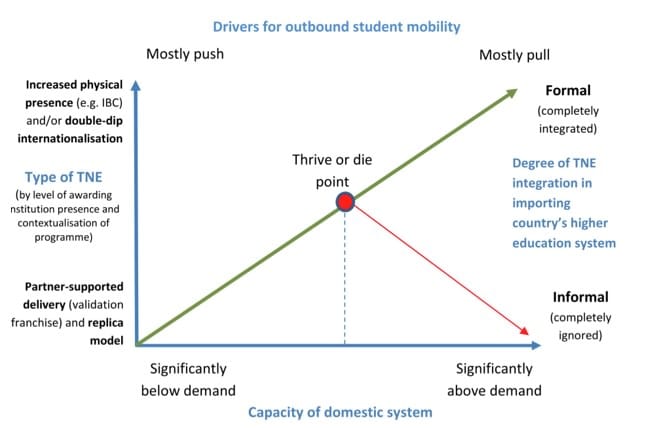

In the early stages of developing programmes in a given host country, TNE is developed as a way to expand supply and improve access to higher education for students who cannot be accommodated by domestic institutions. At this stage, TNE students’ decision-making is primarily geared by push factors (e.g. limited access to education, poor quality of domestic institutions). Partner-supported delivery (e.g. franchise, validation) is therefore often an appropriate form of TNE in early stages of market development.

As domestic capacity develops, students’ decision-making is influenced more by pull factors (e.g. programme quality, reputation of awarding institution, employability prospects). This means that as an offshore TNE market matures, early forms of TNE such as franchising will be less effective to satisfy demand within an increasingly competitive environment. TNE-exporting institutions should consider increasing their physical presence and/or contextualising their programme offerings beyond the replica model at this stage.

At some point, the market reaches a “thrive or die” point where TNE is either integrated or not within the domestic higher education system. As supply expands, if TNE is not integrated in this sense, then the long-term viability of TNE programming in the country will be at risk. This is because TNE programming may appear over time to be inferior to the domestic HE institutions even as TNE-exporting institutions may be constrained in expanding their physical presence in the market. Therefore, the integration of TNE in the domestic system can be seen as a prerequisite for the long-term sustainability of transnational initiatives.

These major stages of market development are reflected in the following figure.

The ongoing expansion of TNE

The past decade and more has seen a marked expansion of TNE activities. This has been particularly true in Asia, where the capacity of local systems has not been sufficient to cover the booming demand for higher education. The current evidence, both quantitative and qualitative, points to a continuing expansion of TNE in the years ahead – in terms of the number of programme offers, the range of TNE collaborations, the number of countries involved, and the number of students enrolled in TNE programmes. This continuing growth will be driven by a number of factors, particularly the following:

- The extensive, ongoing capacity building of offshore higher education systems, primarily in Asia. In many Asian markets, TNE has been incorporated into government strategies to expand the domestic higher education capacity.

- The shift of global economic activity to Southeast Asia, traditionally a major source of international students, thereby creating expanded opportunities for students to remain in their home country or region to enter the employment market after graduation.

- The prevailing demographic trends of major markets such as China, India, Pakistan, and Indonesia, to name a few, are fueling forecasts of strong future demand for higher education in Southeast Asia.

- Increased competition in “home” higher education markets is driving interest in developing new revenue streams offshore, including via TNE.

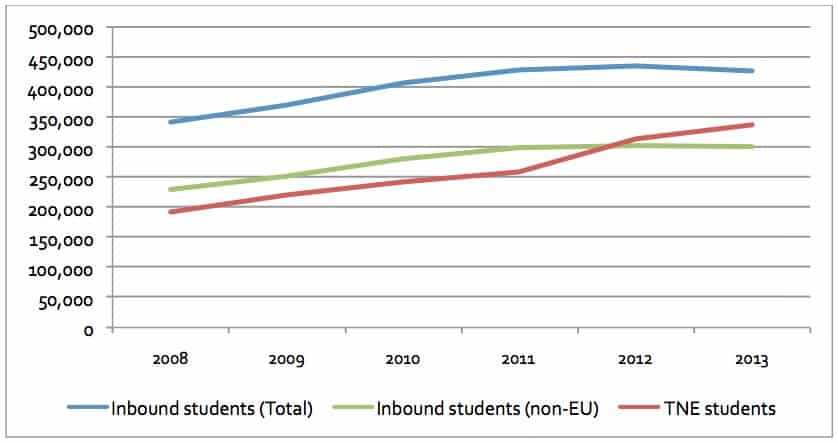

For further insights into TNE growth trends and their relationship to international student mobility, let us look at some of the relevant data from the UK and Australia – two key exporters of TNE services and also leading destination countries for international students.

UK trends in TNE

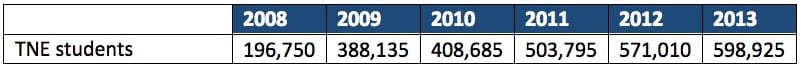

The number of students studying wholly overseas on a UK higher education award reached 598,925 in 2013.

The TNE situation in Australia

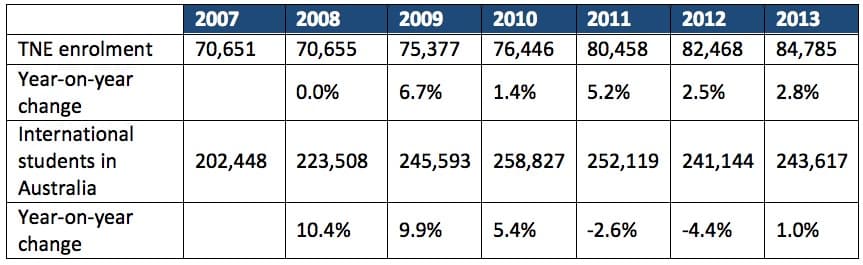

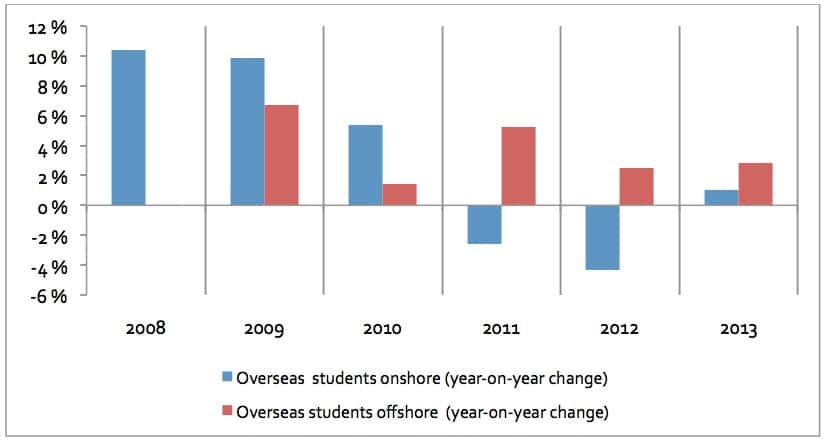

The number of students registered in Australian offshore programmes reached 84,785 in 2013, up from 70,651 in 2007. In comparison, 243,617 overseas students entered Australia to study in 2013, whereas 202,448 foreign students were enrolled in Australia in 2007.

As the year-on-year change of the two export modes indicates, Australian TNE has grown at a relatively steady pace while in-country enrolment, albeit a much larger export area by enrolment, has experienced more fluctuation.

TNE vs student mobility

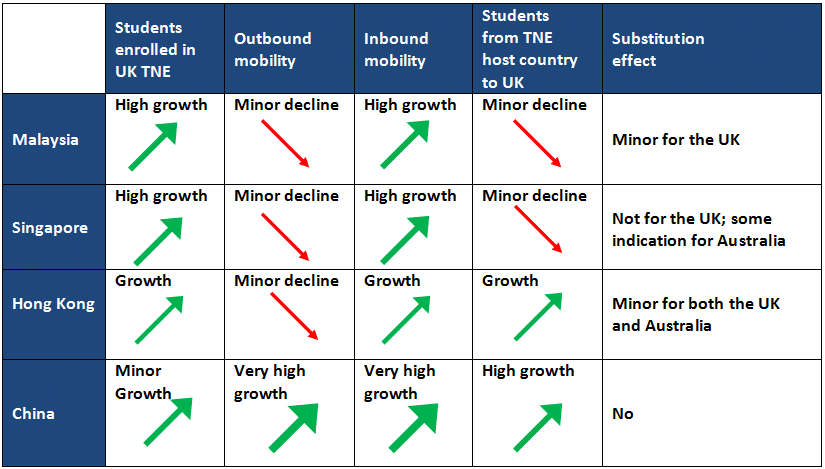

Given the increasing scale of TNE programming in key international education markets, the question naturally arises as to whether there are any substitution effects of TNE on traditional international student mobility. In other words, does greater access to higher education via TNE programmes discourage students from those countries from studying abroad? A recent OBHE project explored the extent to which any such substitution effects exist in the context of the UK and its four top TNE host countries: Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and China. The project set out to address the following research questions:

- What are the factors affecting student choice of TNE vs outbound mobility?

- How do TNE and international student mobility trends compare in each of the top TNE host countries?

- How has the growth of TNE enrolments in top TNE host-countries impacted the number of outbound students from these countries studying in the UK?

The project relied on quantitative data from HESA and UNESCO, along with qualitative evidence from personal interviews with TNE professionals. Our key findings included:

- There was strong enrolment in UK TNE programmes in all four countries examined.

- Outbound mobility of students from TNE host-countries to the UK appears to remain either unaffected or grows. This indicates the absence of a direct substitution effect between TNE and outbound mobility for all countries explored in the project. In the case of Malaysia and Singapore, there was a minor decline in the number of students from these countries who travel to the UK for higher education studies. However, this cannot be attributed entirely to the growth of TNE, instead this is explained by the broader expansion of capacity in domestic education systems.

- A notable common finding in all major TNE host countries is the concurrent decline in outbound student mobility and the increase in inbound student mobility. This is attributable to government policies targeting the capacity development of the domestic higher education system to reverse brain drain and increase the number of inbound mobile students.

- China appears to be an exceptional case where inbound and outbound mobility have both grown at very high rates. China is the world’s top source country for international students as well as an increasingly important regional destination for inbound students.

Overall, our research finds that TNE does not act as a direct substitute for outbound student mobility. Rather, it is part of the capacity-building process in TNE host countries. TNE is still a much smaller area of education export in comparison to international student mobility. Further, the minor impact of TNE on outbound mobility to the TNE-exporting country reinforces the argument that the two modes of export are separate and that they attract different types of students. Dr Vangelis Tsiligiris is an economist who has completed post-graduate studies in management and earned a PhD in TNE. For more than 10 years, he has been engaged in setting up and leading transnational partnerships involving UK and other European universities. His research interests include TNE, student experience, quality management in transnational partnerships, and international strategy in cross-border higher education. He is very active in social media where he leads the Linkedin group Transnational Higher Education. He is currently College Principal at College of Crete and honorary lecturer at University of Liverpool and University Roehampton where he teaches courses in leadership and business strategy in the online MBA programmes.