Peru positioning to be the next big player in Latin America

Peru is a fast developing, tropical, Andean, and Pacific Rim country whose education sector is going through a tectonic shift. Those changes, some of which raise constitutional questions, have unsettled segments of Peruvian society, yet may signal opportunity for international educators and agents to serve students' needs. Today ICEF Monitor offers a market snapshot of the evolving Peruvian higher education sector.

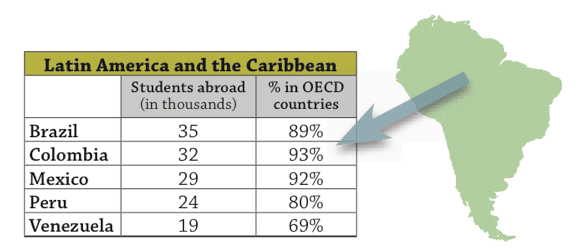

A mobile student population

The most recent available data from the OECD shows that Peru sent approximately 24,000 students abroad in 2011. Inbound data is not readily available, however the latest IIE Open Doors mobility report shows Peru’s popularity with US students increased by 9.5% in 2011/12.

“Peru will be the next market in South America. From our point of view, now is the right time to go for it.”

Others agree. In September 2013 ICEF Monitor interviewed Carolina Cardoso from C2M Marketing & Eventos, who also said now is a good time to enter the Peruvian market.

The golden mean

The debate now gripping the country is whether the government’s changes to the higher education sector are for better or worse. A series of laws creating an alphabet soup of new oversight bodies have come into effect, and more are working their way through the national legislature. But university autonomy is constitutionally enshrined, and students and academics are questioning the legality of the government’s intentions. When President Ollanta Humala Tasso sent his latest bill to congress asking for the creation of a Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Superior Universitaria (SUNEDU), the country’s Minister of Education Jaime Saavedra-Chanduví took the opportunity to articulate some of the government’s plans. Saying that higher education “cannot be entrusted to a mistaken notion of autonomy,” he called for efficient but restrained regulation. In his remarks Minister Saavedra-Chanduví used the phrase “el justo medio,” which is a colloquialism that translates as “the golden mean.” He said the government’s goal was to assist and guide students who cannot know if they made the right university and career choices until years later. However many students feel that the golden mean is a mirage. When the government’s initial tertiary sector reforms were unveiled in late 2013 in the form of the University Act, student representative Alvaro Quintanilla, speaking to the website Peru This Week, pointed out several areas of contention. Among those are: the law eliminated previously guaranteed student benefits such as cafeterias, residences, and transportation, limited extracurricular activities, and reduced campus voting rights. In addition, a new oversight group called the Superintendencia Nacional de la Universidad Peruana (SUNAU) would be comprised of representatives from academia, government, and business - but not students. Negative reaction was swift. Students demanded inclusion into SUNAU and criticised corporate participation, adding more grievances to a list that has been growing since the unveiling of the University Act in 2013. As recently as May 2014 principals, teachers, administrators and students numbering in the thousands marched through downtown Lima in protest of SUNAU, SUNEDU, and the University Act as a whole. The government, meanwhile, is pushing ahead. Minister Saavedra-Chanduví remarked to an Inter-American Development Bank gathering in mid-June that reform was needed because Peruvian higher education was “at high risk of potential internal power fiefdoms.” He described the workforce being currently produced as lacking relevance in both quality and training. Editor's Note: In late June, the New University Law passed Congress, officially creating SUNAU, which will monitor the quality of Peruvian higher education, control the use of universities’ resources, and approve or deny licenses for opening new universities.

Peru’s tertiary sector

One thing that is agreed upon on all sides of the debate is that Peruvian education needs improvement. At the secondary level, the country fell in the OECD’s 2012 PISA tests two places from 63 to 65, when measured against 2009 results. Peru also ranks poorly across all sectors in English language proficiency (though higher than its Andean neighbours Chile, Ecuador, Venezuela, and Colombia). Peru does have several quality universities, including the privately-funded Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, which QS University Rankings rates 30th in South America, and the public Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, rated 57th. Tertiary sector funding for public schools has been another contentious issue. The government’s 2014 budget contained cuts to public university finances, citing slowed economic growth. Yet in other areas, government investment remains high. For example, scholarship support has expanded to previously unseen levels. Since 2011, the Beca 18 programme has offered funding for studies in Peru and abroad to low income, academically exceptional public school students. President Ollanta Humala Tasso has called the programme, which has awarded more than 11,000 grants and aims to benefit 50,000 by 2016, an essential tool for poverty reduction and fighting the inequality gap in Peru. In 2012, we reported that 1,000 new science and technology (S&T) postgraduate fellowships would be made available by 2016, as well as 1,500 scholarships for Peruvian students at foreign universities. That same year, the Ministry of Economy and Finance launched an Innovation for Competitiveness programme designed to boost S&T links between universities, the private sector, and public and private research centres. The project, with US$100 million of state funding and a further US$36 million from the Inter-American Development Bank, is expected to run for seven years. The Peruvian government also recently launched Beca 18 Excelencia Francia, which will fund studies in France beginning in 2015 with an initial group of 200 awards. The scholarship has been described by officials as a way to develop human capital, and is open to top students from all economic strata. In addition to these, the Beca Presidente de la República (President of the Republic Scholarship) supports international postgraduate coursework and postgraduate research. In 2014, 500 such awards were given for full-time master's programmes (up to two years) and PhD programmes (up to four years). All these programmes exist under the umbrella of Programa Nacional de Becas y Crédito Educativo (PRONABEC), and as of 2014 the number of recipients of the above grants, as well as two others - Beca Docente and Beca Alianza del Pacífico - stood at 29,802. The government’s action plan calls for catapulting that number to 73,000 by 2016.

Economy and education

For yet more encouraging news, one need look no farther than Peru’s economy. Economic growth often means more money for the middle class to spend on education, as well as more demand for quality education both at home and abroad. Peruvian growth rates once topped 6%, and though the economy has cooled due to falling mineral exports, current forecasts still predict 4% growth in 2014, not bad compared to many countries in the region.

As a result of this sustained upward trajectory Peru’s middle class is twice as large today as it was in 2005. Families’ willingness to spend on education has reshaped the sector from the bottom up. For instance, since 2004 more than a million children have switched from public to private schools, a level of demand that has pushed fees up by 30% to 40% in just the last five years.

Mr Jorquera pointed directly at the economy when he said, “I think Peru is the next player in international education in Latin America. If you analysed what happened during the crisis, Chile and Peru had unusually good results compared with other countries in Latin America. They [grew] even during the worst times of the crisis.” This growth has not gone unnoticed, with the country ranking second place in Latin America for business, and several big brands eyeing Peru for expansion. Facebook is considering opening an office there, and this summer, the British Council plans to re-open their office there (it was closed in 2006). British Ambassador James Dauris said: “There are lots more Peruvians who now want to learn English and get English language qualifications than a few years ago. Collaboration between Peruvian and British universities has been increasing since I have been in Peru. The British Council is already discussing exciting plans with the Peruvian Government to help teachers here improve their English. And having the British Council back in Peru will help to make the UK’s broad educational offer more accessible – from English learning resources and exams to post-graduate qualifications.”

One to watch

The combination of increased economic means and available scholarships indicate that Peru can produce more prospective international students. And it’s important to note that, in general, Latin American students seek study abroad opportunities outside their home region at a higher rate than students from Asia or Europe, a finding highlighted in a recent ALFA PUENTES survey. Though Peruvian students lag in PISA scores and English proficiency, the government has at least taken an active approach to these challenges. Whether its solutions are the correct ones is the question. But with ten academic hours added to weekly schedules in state schools, and reforms to teacher training, textbooks, and more, the next round of student assessments could be very different from last year’s. Educators should monitor the ongoing wrestling match with universities, but for the moment the Peruvian market looks promising for those wishing to partner in the country.