Signs of growing interest in study abroad as Czech Republic aims to stabilise education sector

The Czech Republic has experienced profound change in the last two years, with a constitutional amendment allowing the population to directly elect the president, the dissolution of one government, and the establishment of new leadership to set new directions for the country. During all this, education policy has swung back and forth like a pendulum. ICEF Monitor explores these developments in today's post, alongside current inbound and outbound student mobility trends.

Early and vocational education

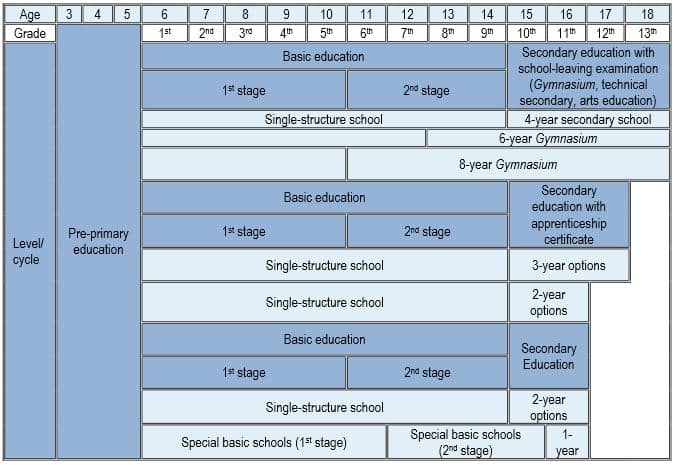

Czech elementary education takes places over nine years, usually between the ages of 6 and 15, comprising a primary and lower secondary stage, with children also given the option of attending a variety of schools utilising different types of educational programmes. Students also can apply to six or eight-year gymnasiums after their fifth or seventh year of elementary education, or attend a conservatory. These varying options for elementary education pave the way for the pursuit of higher education, at the secondary and university stages.

Upper secondary education is either general or vocational, takes place over four years and is not compulsory. Vocational education in this respect is more widespread than general secondary education – indeed graduates with a vocational certificate often decide to pursue work opportunities immediately instead of staying in the education system for further study.

The Czech government works to shape the vocational sector, for example in 2008 it published a National Action Plan laying out support guidelines for vocational education and training, followed in 2013 by a set of near-term organisational, administrative, and legislative goals planned to improve both the quality of the sector and participation levels in it.

The OECD’s Education at a Glance 2013 report indicates that vocational education plays a major role in the Czech Republic's education system, with secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education of this type having over a 70% level of attainment among 25-64 year-olds. The OECD report also notes that among 15-19 year-olds, over 50% are enrolled in pre-vocational or vocational programmes at upper secondary level.

The Czech tertiary sector

The Centre for International Services (DZS) notes that Czech higher education dates back over 600 years ago to the founding of Charles University in Prague by Emperor Charles IV. By law, higher education at public and state institutions is free of charge for citizens of all nationalities, except for the following:

- Administrating admission proceedings;

- Fees for foreign language study;

- Extending the length of study above a set limit;

- The study of an additional programme.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD) Education At a Glance 2013, between 2005 and 2010 the Czech tertiary sector experienced the second-highest increase in expenditure among OECD nations, more than twice the average. More importantly for educators and agents, the numbers of students increased by 32%, again more than twice the average. Increases in funding for higher education continued even during economic crisis in Europe, but eventually the system was targeted for changes. University World News reports how the Czech government under Prime Minister Petr Nečas drafted a plan aimed at shifting to a tuition fee and student loan system. The plan met with vigorous student protests and was scrapped in mid-2012. Since then, as BBC News reports, Mr Nečas was swept out of office by a corruption scandal. The newly elected government, led by Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka, set out its opposition to introducing tuition fees, which the Czech Social Democratic Party (ČSSD) views as a profit scheme for banks and a debt trap for students. If Mr Sobotka’s governance is consistent with his party’s previous statements, higher education costs for students look set to remain low for the foreseeable future. However, the fundamental question of what role learning institutions play and how they interface with the labour market are not permanently settled. The OECD Economic Surveys: Czech Republic 2014 concludes that Czech schools have reacted slowly to changes in employer requirements, resulting in an increasing number of school leavers without sufficient qualifications for the contemporary job market.

Czech students and international ambitions

Another OECD report - Society at a Glance 2014 - offers a set of insightful statistical data about the Czech education system as it currently stands. Of particular note is the fact that the rate of idle youth (Neither Employed nor in Education and Training, or NEET) is now below the OECD average of 12.6%, from 17.1% before 2008 to 9.1% today. This raises the question as to whether prospective students could be attracted, in greater numbers, to study internationally. With free schooling in the country, however, enticing Czechs to study abroad is not easy. World Bank data confirms this, pegging the percentage of Czech tertiary international students at 2.6% of the whole as of 2011, in the bottom fifth among EU member states. A direct drag on outbound mobility is the Czech koruna’s (CZK) weakness against western currencies. In 2007, the government suspended a plan to adopt the Euro, a decision that gave the Czech economy some badly needed maneuvering room to help respond to the growing global economic crisis at the time. The Czech National Bank (CNB) has taken steps to bolster the national economy by increasing the money supply, which has in turn held the koruna’s value low and raised the value of exports. Such measures, however, also makes study abroad a more expensive proposition for Czech students. Even so, opportunities exist for those with good local contacts, as a report on the website Radio.cz indicates. In an interview with Radio.cz, recruiter Klára Macíková, who works with the University of Worchester, notes a rising interest among Czechs in going abroad. Ms Macíková points out as well that there is little knowledge of the requirements for study abroad among Czech students, particularly with regard to financing that might be offered by overseas schools. Speaking to ICEF Monitor, Samuel Vetrak, CEO of StudentMarketing details the extent to which students in the Czech Republic opt to study abroad. Mr Vetrak says that almost 12,000 Czech tertiary education students (approximately 3% of the tertiary student population) study abroad for one year or more (short-term programmes, such as Erasmus, not included). He notes that Slovakia is the leading destination, hosting 4,979 students from the Czech Republic in 2011, and notes that Germany, the UK, the US, Austria, and France are among other popular destinations. Mr Vetrak adds that "these six destinations attracted 80% of all Czech students" and explains the extent of interest and demand for study abroad:

"Approximately 80,000 young adults (18-25) are interested in studying abroad in the coming 12 month (all levels of study, 45% at university). Social networks and local teachers are the most-used channels of information. The highest demand is among those youngsters who have already studied abroad (9% of the young population). Educational agencies are the most popular booking channel, although this is less true in Prague or among those who have already studied abroad (such students are more likely to book online/directly).”

Student mobility to the Czech Republic

Turning to the question of inbound students, Mr Vetrak notes that the Czech Republic is a “significant regional hub within Central and Eastern Europe.” He underscores that, “over the last decade, the number of international students studying at the tertiary level has increased fourfold”:

“In 2012, the country attracted 39,696 students, with vast majority of these coming from Slovakia. Apart from Slovakia, countries sending the highest number of students are Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan. The Czech Republic has been and is becoming increasingly a more strong study destination in Russia and CIS countries. The quality of education at some institutions and relatively friendly visa policy and marketing support from many educational agencies promoting this destination make the Czech Republic an attractive option in the aforementioned source countries. The country has become popular for tourists and business people as well, enhancing the popularity of Prague and Czech Republic too.”

This trend comes at a time when international interest in Eastern European higher education is increasing. According to a recent New York Times article, medical, dental and pharmaceutical studies in the region are drawing students from abroad, and have contributed to a doubling of foreign students in the Czech Republic between 2005 and 2011.

An important change in the education sector

In February, the Czech daily Mladá fronta Dnes revealed that the government plans to tighten the controls on teachers of English. Since most US teaching certificates are not recognised in the Czech Republic, many American teachers do not currently possess appropriate qualifications. But barring undocumented workers could create an ESL teacher shortage in the country, particularly because British teachers are much more reluctant to accept the lower salaries afforded language teachers in the Czech Republic (typically around CZK 25,000 per month [US $1,263]). In a related development, Prague Post reports that in early March, Education Minister Marcel Chládek announced that some categories of teachers can continue working, including part-time teachers of specialised subjects and teachers over age 55 with more than 20 years of teaching experience. Such measures would affect the 130,000 teachers in the Czech Republic, 17,000 of which do not possess the required qualification. Going forward, the Czech news agency Česká tisková kancelář (ČTK) reports Minister Chládek intends to improve the Czech school system, and to bolster its competitiveness in relation to other countries. To do so, he hopes for a budget increase, and has mentioned an increment of CZK 3–5 million (between US $150,000 and US $250,000) as a target. He also suggests that money could be raised from EU subsidies and by restructuring vocational schools or school leaving exams. But after several years of government instability and accompanying policy swings that have brought the sector from edge of radical change to what now appears to be greater continuity of the traditional system going forward, the country may benefit most from a period of cohesive policy (and stable, increasing funding) that will allow Czech students to plan for their future. Events in 2014 will go a long way toward determining the extent to which that will happen, and will no doubt bear significantly on trends in education at home and patterns of international student mobility as well.

Most Recent

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More