How post-study work rights can make or break the return on investment for study abroad

The following is a guest post contributed by Tim O'Brien and Claire Clifford from INTO University Partnerships, where Tim is the Senior Vice President, New Partner Development, and Claire the Vice President, Pricing, Insights and Research.

According to a 4 June 2025 Wall Street Journal report, international students contribute over US$40 billion to the US economy. The article mentioned rumours of potential curbs to Optional Practical Training (OPT), a key pathway for foreign graduates to gain work experience.

In the UK, the Government has announced its intention to reduce post-study work term of the Graduate Route from two years to 18 months. As our latest research shows, these adjustments threaten to undermine the very model that sustains this student flow. What was once a soft benefit is now a critical pillar of financial viability.

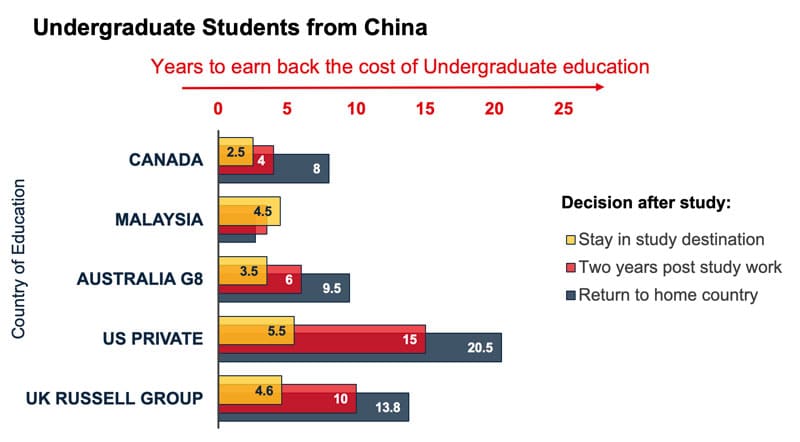

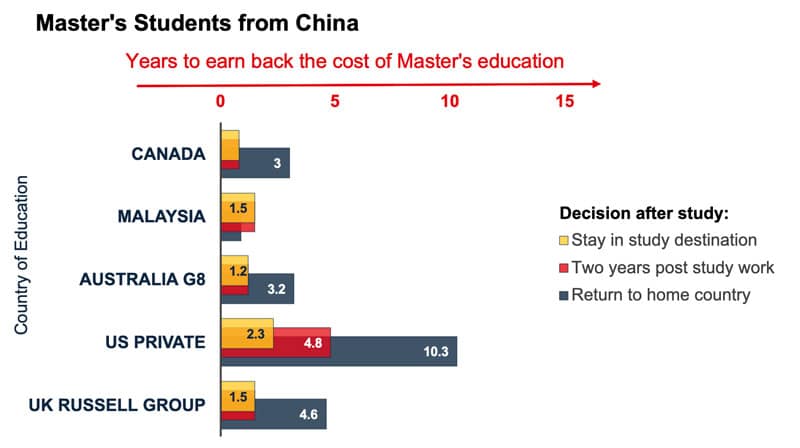

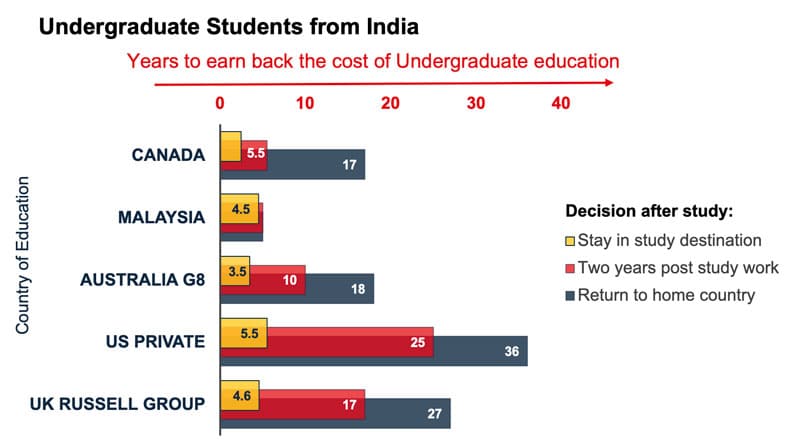

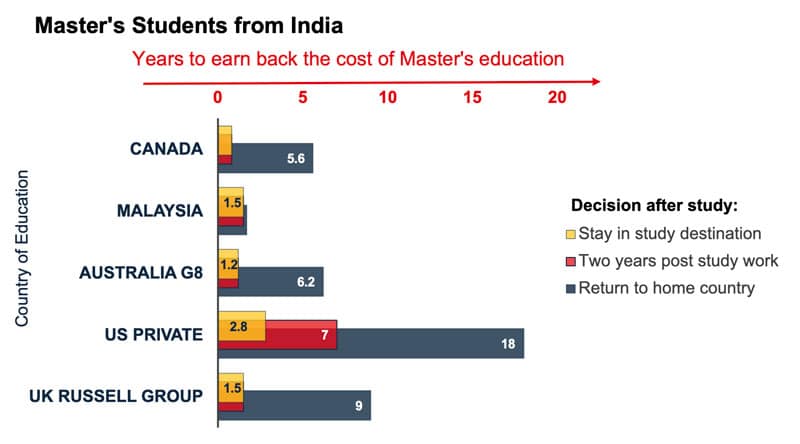

An Indian student returning home immediately after a US undergraduate degree at a private university could work more than 30 years to recover the cost. Stay and work for two years post-graduation, and that figure drops by 11 years, or as little as three in Canada and Australia. For Chinese graduates, a stint of post-study work can cut almost six years from the payback period. (These figures are based on average graduate salaries in the relevant countries and allow for taxation at prevailing rates.)

Across scenarios, students who can work after studying earn back their investment much faster than those who cannot. The economic impact is undeniable—and increasingly, unavoidable.

China

As we see in the first chart above, students returning to China immediately on graduation would need to work for almost 14 years to earn the equivalent cost of a three-year undergraduate Russell Group education (including living expenses), and for four years less, if they took advantage of a two-year post-study work opportunity. Masters students who return home immediately can earn the total cost of a one-year Masters in around 4.6 years but can reduce that recovery time by half if they do some post-study work in the UK.

The same undergraduate student who works in a graduate level job in the UK and then returns home can cut almost five years off the repayment term, earning the equivalent back in just under four years.

India

The charts again reflect that students returning to India immediately on graduation would need to work for 14 years to earn the equivalent cost of a three-year undergraduate Russell Group education (including living expenses), and for two years less, if they studied at a non-Russell Group university. Masters students who return home immediately can earn the total cost of a one-year Masters in just under five years.

The same undergraduate student who works in a graduate level job in the UK and then returns home can cut more than eight years off the repayment term, earning the equivalent back in just under five and a half years.

But universities cannot rely on immigration policy alone to make education affordable. Reducing fees may not be fiscally viable. Instead, institutions must rethink delivery. Offshore degrees, hybrid models, and transnational partnerships offer students the chance to begin their studies at home – at lower cost – and finish overseas, gaining the international exposure and credentials employers value most.

These shifts are happening at pace. An opinion piece in Times Higher Education by Dr Cheryl You points out that, “More students are opting for in-country pathways, such as foundation programmes or 2+2 joint degree arrangements between Chinese and Western universities, as more practical and supportive alternatives. In addition, they are increasingly looking beyond traditional overseas study destinations to closer-to-home alternatives, such as Hong Kong, Macao or elsewhere in Asia.”

And, as for post-study work, it is a critical part of the offer for students. It is not a pathway to permanent migration nor a drain on public resources. Students on post-study work in the UK pay an additional surcharge to use [National Health Service] services, for example. A period of post-study work makes a world class education more affordable for students and provides the receiving country with a valuable talent pipeline – especially in areas where there are major labour shortages – such as in technology and other skilled fields which are such important drivers of economic growth.

For universities and policymakers alike, the message is clear: that return on investment for the visiting student is no longer optional. Rather, it is increasingly the global currency of trust in higher education. Global student mobility works best when the math does too.

A note on methodology: We used an average of tuition fees and living expenses for each of the destination countries.vOur team then calculated graduate starting salaries – net of income tax for each of the three post-graduation options.