Study highlights gaps between English standards set by test developers and those used by universities and professional bodies

- Test developers provide evidence-based guidance on proficiency benchmarks for university admission or professional practice

- However, a recent study finds that both universities and professional organizations tend to depart from those recommendations when setting proficiency requirements

- There are a number of factors behind that variance, including heightened competition among institutions, and the lack of a unified system for equating the major English proficiency tests with each other

"Professional bodies and universities may have different standards when using English language proficiency tests for recruitment. This is the headline finding from a 2024 study – "Benchmarking English standards across professions and professional university degrees" – an effort jointly funded by the British Council, IDP, and Cambridge University Press & Assessment.

"We were really shocked by how institutions set test scores that widely deviated from test-maker recommendations, which are based on linguistic experience and evidence," said study co-author Dr Amanda Müller of Flinders University in Australia. "We were most surprised by how different institutions varied so much in how they interpreted equivalency across English tests. The standardisation of equivalence scores is crucial."

Aside from that misalignment between minimum score requirements set by universities and those set by professional bodies, the authors found there was no unified system for equating scores across the major English proficiency tests. They also concluded that neither universities nor professional bodies consistently follow the recommendations of test developers when setting minimum requirements.

For example, whereas professional bodies in the field of education set an average minimum IELTS score of 7.1, universities providing education degrees required, on average, IELTS 6.6. And where professional legal bodies required an average of IELTS 7.2, law schools specified an average of 6.5 for admission.

Across all professions assessed for the study, professional bodies required an average of IELTS 7.0 whereas universities providing professional degrees in the same fields asked for, on average, IELTS 6.6. "This means that universities are admitting students into degree pathways with a score lower than that required for professional registration," note the authors. As to the significance of that gap, the authors explain that, "A variation of half an IELTS band score is more significant than it may sound. Research has shown that for a student to improve by a 0.5 band score, they would need to study English for up to 6 months full-time because gains are slower at higher levels than lower levels."

In addition to that gap between professions and universities, the study also highlights that both sets of minimum requirements can often depart from test-developer recommendations as well.

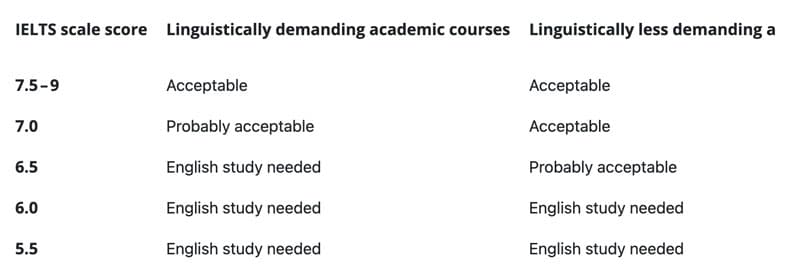

For a "linguistically demanding" academic programme such as the ones evaluated in the study (e.g., education, law, medicine, psychology) IELTS recommends a 7.5 band score in order for an applicant to demonstrate an "acceptable" level of English proficiency. A score of 7.0 is rated by IELTS as "probably acceptable". The following table expands on that official guidance.

Mind the gap

As to the factors behind those variances in the standards set by universities, the professions, and test developers, Dr Müller says, "International education is a fiercely competitive market. I can tell you from experience that institutions look to their peers when selecting their standards. This is definitely a common practice in both university and professional requirements. It forms part of the evidence base when they try to put changes through senate and boards."

In other words, a university may be more inclined to set its requirements based on the admissions standards of other universities in their home region or country, as opposed to the evidence-based recommendations of the language experts who developed the test.

Dr Müller highlights as well the study's findings with respect to test equivalency as other possible factor. "[An] international student may have got in on an English test that was not IELTS and was poorly equated. This is the other huge problem: that institutions choose and post scores on different English tests as ‘equivalent’ for them. However, when you look at the proper equivalence studies and even what other institutions are deciding, the scores they chose are clearly not equivalent." This sets up loopholes in the admissions process that can be exploited: "Potential international students can game the scores for different tests at different universities until they get the one that they can reach with their lower levels of English skills."

In order to minimise those discrepancies across the major English proficiency tests, the study sounds an urgent call for the standardisation of equivalence scores. “Test developers could be encouraged to create a single equivalence table of their tests as an important exercise to improve trust and reliability of language proficiency testing," conclude the authors.

For additional background, please see: