Building to scale: Are agent aggregators changing the dynamics of international student recruitment?

- Agent networks are not new but so-called agent aggregators are building those networks at a scale the industry has not seen before

The following feature is excerpted from the 2022 edition of ICEF Insights magazine and is reprinted here with permission. The entire issue of the magazine is available to download for free at icef.com/insights.

The Internet is a great example of what economists refer to as the “network effect” – a phenomenon in which the value of a product or service depends on how many people use or participate in it. As more people join, the product or service becomes more helpful or efficient.

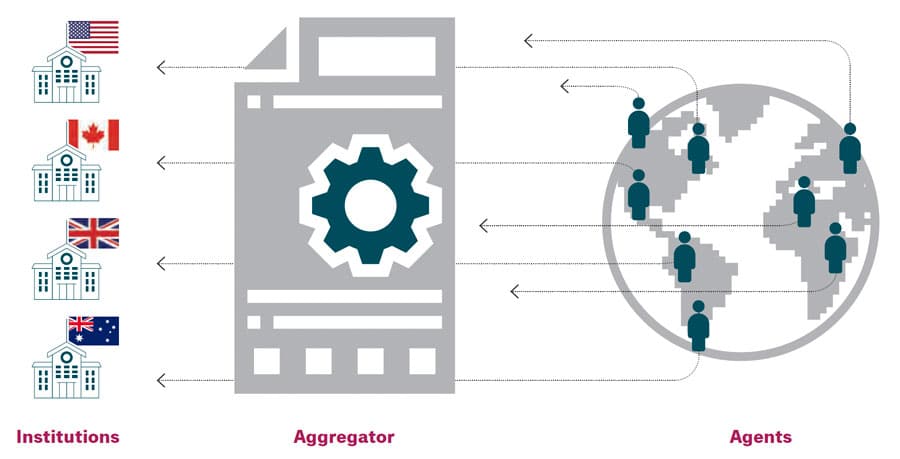

The network effect is the driving force behind a growing number of online platforms used for international student recruitment. Sometimes referred to as “agent aggregators,” these companies connect large numbers of educators, typically across a variety of study destinations, with an even larger pool of education agents.

Institutions and agents access an online platform boasting targeted services and features. The goal for institutions is to recruit large numbers of students more efficiently. Business models vary, but typically the recruitment platform retains a share of a referral commission from an institution or school, with the balance passed on to the agent.

There are differences between companies in this sector, despite their common purpose. Some rely more on artificial intelligence, for example, while others operate as exclusive recruitment partners for their institution clients.

High-profile examples of such recruitment platforms include the venture-capital-backed ApplyBoard and Adventus.io. Established university pathway providers, such as Shorelight or INTO University Partnerships, can also be seen to play an aggregator role; newer operators are entering the space every year, such as Edvoy, MSM’s Abcodo, and Leverage Edu’s UniValley platforms.

How fast are they growing?

The idea of the agent network is hardly new, and sub-agent relationships between larger, established agencies and smaller, geographically distributed offices have been common for years. What is different here is the scale at which some of these newer tech-enabled platforms operate.

The network effect is in full bloom for platforms such as ApplyBoard and Adventus.io, which have both dramatically built up their respective agent networks over the past two years. As of July 2022, ApplyBoard reported a network of roughly 10,000 agents while Adventus.io had built a network of about 6,000 agents by that point.

These growth trends reflect an important point: for the aggregator model to work, the platform must attract a critical mass of both institutions and agents. Without a sufficient variety and range of partner-educators, the platform cannot recruit and retain agents. Without an impressive agent network, the platform cannot engage enough institutions or meet their recruitment goals.

Supporting the network

With networks this large, it is natural to wonder about the degree of quality assurance and oversight these platforms can provide. Educator surveys exploring the subject have certainly revealed concerns about the transparency and quality of agents and student-applicants.

For their part, executives for recruitment platforms report that they rely on a range of quality assurance measures, such as using structured onboarding processes to register and vet new agents. “We take recruitment partner vetting and training extremely seriously,” says Meti Basiri, co-founder of ApplyBoard. “Each recruitment partner is vetted with our thorough vetting process. Typically, on average, we reject about 40% of recruitment partner applications and the vetting doesn’t end once they sign up on the platform; it continues throughout the recruitment partner’s time on the platform.”

In most cases, any technology-enabled processes and monitoring on recruitment platforms are supported by people. Quality assurance at Adventus.io, for example, relies heavily on specialists whose prior careers were in the areas of immigration or admissions processing.

“Technology is great, but when it comes to looking at applications, the most powerful computer on the planet is the human brain,” says Chris Price, senior vice president of partnerships for Adventus.io.

He continues:

“Before we lodge an admissions application with an institution, our admissions team assesses each application against entry requirements, vets every document for accuracy and completeness, and assesses for visa eligibility as well. On average, we find that 30% of applications received are not ready to be lodged with an institution. This is all designed to ensure that institutions receive only high-quality applications that can result in admissions offers. In fact, 90% of applications generated through Adventus result in an offer from a partner institution.”

Most recruitment platforms also operate under codes of conduct for registered agents, with interventions – including additional training or even sanctions – on the table in cases where an agent is the subject of a complaint or where other concerns indicate that good practice guidelines have been breached.

Pros and cons

Technology-enabled recruitment platforms represent a quick, efficient way for an institution to greatly extend its international recruitment network. At the same time, the model offers agents an expanded roster of institutions abroad without the need to establish individual agreements with each.

Without a doubt, there’s something compelling about this approach – indeed, the rapid growth of such platforms has proven this out. The appeal can be especially apparent for institutions that are trying to enter more international markets or that have not yet established agent networks of their own. Similarly, recruitment platforms can be attractive to newer agencies or those that have not yet established direct relationships with educators in a particular country.

Nevertheless, critiques of the model persist. Concerns often relate to the transparency and accountability of agents, who, in their relationships with institutions on the platform, effectively operate as sub-agents. For the agent, working through a recruitment platform may mean they do not have an opportunity for a direct relationship with the educator.

There is, in effect, tension between the efficiency of the networked platform and the natural interests of the educator and the agent to be directly accountable to each other in their combined services to students. Along with the ability to scale up networks quickly, this tension is at the heart of the aggregator model, and it will likely continue to shape the development of these quickly growing platforms.

For additional background, please see: