Do international students face additional barriers in accessing mental health supports?

- More than one-third of international students responding to this year’s International Student Barometer survey report feeling stressed

- 42% are worried they might not be able to complete their studies

- Even so, only a modest percentage of foreign students access mental health services during their studies

- This bears on retention and recruitment as “happy, well-supported students are more likely to complete their studies and recommend their institution”

High levels of stress among international students attest to the continuing impact of the pandemic on a generation of students whose studies have been disrupted in some way over the past three years. In part two of our coverage of i-graduate’s 2022 International Student Barometer (ISB), we look at the results highlighting which student groups are the most likely to report high levels of anxiety – and what the implications of this are for educators.

Good news first

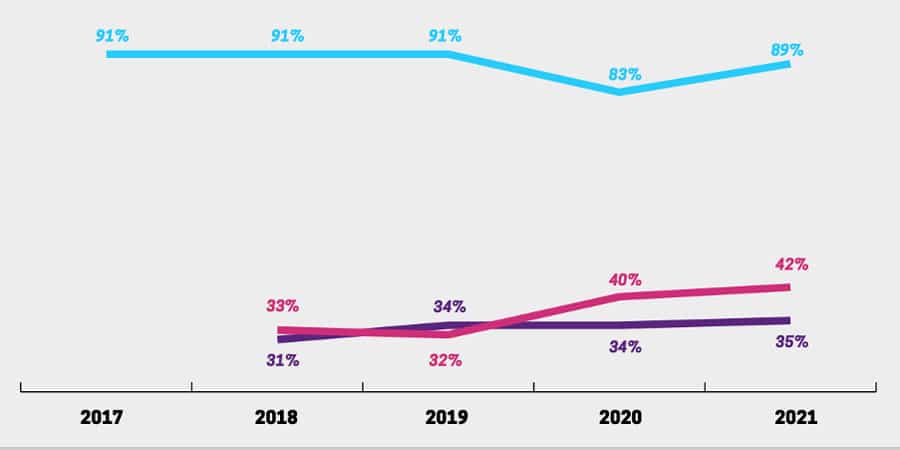

The 2022 ISB found that “international students’ happiness with their life at their institution appears to be returning to pre-COVID levels,” with 89% reporting that they are “happy” or “very happy” in this regard. This is up from 83% in 2020 and it nears the proportion of students reporting happiness in 2017 (91%).

But worry underlies the experience

What hasn’t rebounded are students’ stress levels – at 35%, these are a percentage point higher than in 2020 and four percentage points higher than before the pandemic in 2018. Contributing to students’ anxiety is their worry that they might not be able to complete their studies, perhaps related to their recent experience of having been unable to begin/resume studies abroad during the height of travel restrictions and/or to learn in person, on campus. Fully 42% of students said they were worried that they might not be able to complete their studies in 2021, up two points from 2020. This rose to 49% of students whose studies had moved entirely online.

Stress levels higher among offshore and undergraduate students

While the average of students saying they were always or often stressed or anxious was 35%, this rose to 45% of offshore students who were studying online. More than 4 in 10 undergraduates are also reporting more stress than the average – 41%, versus 32% of postgraduate-taught and 28% of postgraduate research students. ISB report authors suggest that “it’s likely that this is related to life experience, with many undergraduate international students living overseas for the first time, usually without family.”

Only a small minority using counselling services

In 2021, 16% of students told the ISB that they were using counselling services at their institution. Those who had used these services were generally satisfied (89%), but the fact that only 1 in 6 students had used them at all is worrisome in an overall context where significant proportions of students are experiencing stress during their studies. Close to a quarter of surveyed students (22%) said they did not know how to access counselling.

Far-reaching implications

Many institutions have invested heavily in improving and/or expanding their support services for international students as a result of the pandemic, but the ISB highlights that in general, this investment needs finetuning in order to reach the student groups most in need of counselling and reassurance. Students who are distressed naturally find it more difficult to succeed in their programmes, and the ISB report authors remind us that “happy, well-supported students [are] more likely to complete their studies and recommend their institution.”

Gaps in awareness and delivery of services

An interesting report written by members of the Graduate Student Association (GSA) in 2021 – “Strengthening International Students’ Access to University Support Services” is based on the feedback of more than 600 University of Melbourne graduate students from 47 countries who were studying at the university that year.

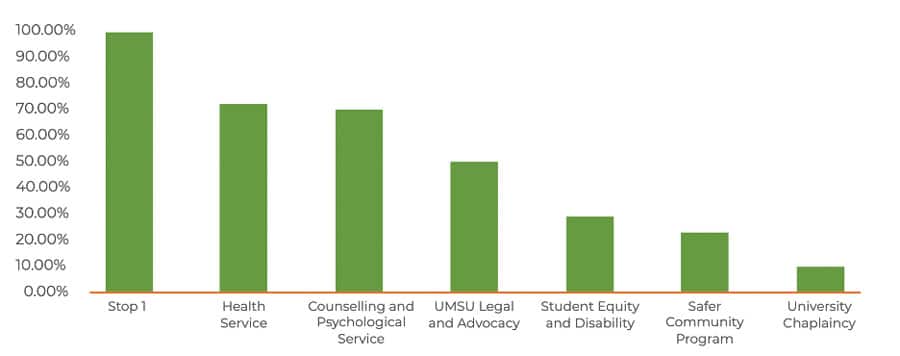

The report notes that the university offers a range of support services to international students, but that students are more aware of some services than others. The very first service that almost all international students reported knowing about is called Stop 1, “a centralised information hub that connects students with information around enrolment, student administration, booking support services, peer programmes and course advice.” To access this service, “students call, message, e-chat, or have face-to-face appointments by booking online.”

High awareness of Stop 1 led the report authors to conclude that this service should be marketed widely to increase the reach. This idea gains traction when considered alongside one of the student verbatims included in the report:

“I only realised there are such support services when I almost finished my degree. So, it would be great if the university could officially send an email to new students telling them all the resources they can access at uni, in particular to international students because they basically know nothing (including what resources are there, how they work, how to access) when they come to Australia initially.”

After Stop 1, however, international student awareness of other supports dropped off and student comments indicate that there are several barriers preventing students who are aware of them from using them optimally or at all.

Those barriers are almost certainly common at universities in other countries as well, and University of Melbourne students’ comments about them can provide generally applicable insights. For example, many students found it difficult to access “simple plain language information about how to book an appointment or healthcare requirements … some respondents were unsure about the cost of the programmes and if the University counselling and health appointments were included in their Overseas Student Health Cover.” Reducing confusion and uncertainty would almost certainly boost use of the services.

Other problems students mentioned included:

- Long wait times to get counselling appointments;

- Staff who did not speak a language other than English and who lacked awareness of cultural differences;

- Worries that if they revealed a mental health challenge, their enrolment status would be jeopardised;

- Lack of regular communication about available services.

Students offered recommendations as well:

- 60% recommended shorter waiting lists;

- Over half suggested increasing the number of online counselling appointments;

- Many emphasised the need for clear and updated information on university FAQ pages.

Offshore students may face privacy barriers

A 2021 article in Canadian education journal University Affairs (UA), “How mental health Services pivoted during COVID-19”, examines some of the issues remote and/or offshore students can face if they decide to access online counselling. For example, one student interviewed for the article “tries to schedule her sessions for when her family is out of the house,” while another “wears headphones and lowers her voice when speaking with her therapist since some of their discussions focus on her feelings of isolation or anxiety around her family.”

Tayyab Rashid, a clinical psychologist at the University of Toronto, told UA that she has worked with many students who simply can’t discuss the problems that are at the heart of their stress “such as past trauma or sexuality” because their living situations aren’t private enough. He said he’s conducted some sessions with patients “on their balconies or in their closets” so that patients feel safe to discuss sensitive issues.

Offshore students may also feel less connected and trustful of their institution because they haven’t been there and met staff and students in person. It can be difficult for students to let down their guard and trust that the information they divulge will be kept confidential and secure.

Some offshore students just aren’t able to access mental health supports from their institution because of legal restrictions. Interviewed for an article published by Australia’s ABC News, Indian student Ashrika Paruthi explained that offshore students’ stress can be extreme due to their worry that studying online in their own country will not lead to the job and career they want to pursue. But Ms Paruthi noted, “According to Australia's law, you cannot really access mental health care support, you cannot basically get in touch with a certified therapist or counsellor, if you're offshore.”

A work in progress

Jennifer Thannhauser, associate director of counselling at the University of Alberta in Canada, told UA that “while tons of new services, apps and websites have popped up during the pandemic, not all tools are worth the investment.” She also said,

“One of the pieces that slowed us down in terms of enhancing or adding more virtual services is that it is so hard to figure out which services truly are legitimate and also meet the privacy needs of our institution."

Patrice Cammarano, founder and co-president of St. Thomas University’s mental health society, says that for students, “the overlapping resources makes it hard to know who to contact.”

Many universities’ rush to develop more mental health services during the pandemic is of course laudable and necessary. Clearly, however, many institutions are still trying to figure out how best to develop and deliver effective counselling to different groups of international students – especially those studying online, who, as the ISB survey reveals, are the most likely to suffer anxiety or depression.

For additional background, please see: