Can English assessment tests help to build a more diverse enrolment?

This special feature is sponsored by Cambridge Assessment English.

The decades between 1990 and 2010 were marked by a remarkable surge in international student mobility. The number of students in higher education abroad more than tripled over that period to reach roughly 4.5 million by the start of the 2010s. From that point on, however, the global growth curve for international education began to flatten out. In 2018, a British Council report projected that average annual growth would slow from the 6-7%-per-year pace recorded between 2000 and 2015 to a more moderate rate of roughly 2% per year through 2030.

The issue, in large part, is that outbound numbers from the key Chinese market had begun to slow over the last decade and are now projected to grow more modestly into the future. China has been the engine of growth in global mobility for many years and the shifting demand patterns for Chinese students and families marked something of a sea change in international recruitment. There is no question that China, and more recently India, will continue to be the key sending markets for most study destinations. But many institutions and schools have also put a greater priority in recent years on opening new markets and building more diverse student populations.

That priority of expanding recruitment reach can now be seen through the additional lens of the pandemic, when, for some students and providers at least, student mobility came to a standstill. As we all now work towards rebuilding international enrolments after COVID-19, we do so knowing that the international student marketplace will be more competitive than ever before.

As international programme directors and admissions managers consider how to broaden their prospect pools, they are understandably looking afresh at admissions processes and requirements, both to see what lessons learned during the pandemic might be carried forward and to determine if their current practices are well-fitted for new or emerging target markets.

"During the pandemic, many institutions put measures in place to keep student recruitment flowing," says Nicola Johnson, global recognition manager for Cambridge Assessment English. "As we move forward, we need to stop and reflect and ask ourselves, 'How has this worked and what can we do better?'"

"What we're finding is that navigating the English language testing landscape has become an increasingly complex job for admissions managers," she adds. "With the proliferation of [testing] options now available and the pressure to meet targets, most top universities will choose to accept a range of tests and across the world in different regions they use different default certifications."

The clear implication in that is that by accepting a range of tests, a university or college can connect with the most suitable applicants across a wider variety of markets. Also related to student access to testing, we have naturally seen a much greater emphasis on online, on-demand exams during the pandemic, and it seems likely online testing will continue to play an important role going forward, especially in countries where in-person testing options may be more limited.

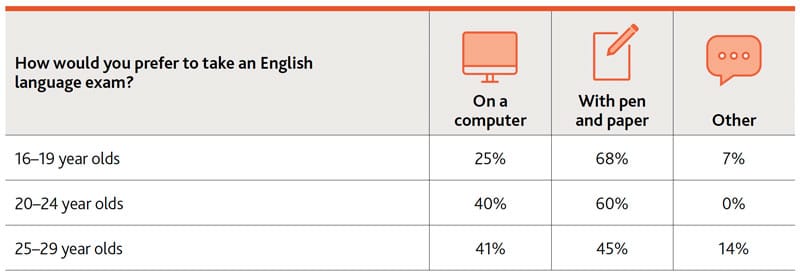

Interestingly though, a recent student survey conducted by Cambridge Assessment English found a strong continuing preference among students for paper-based tests. As the following table reflects, responses from more than 1,200 candidates consistently favoured in-person testing.

"We know that choosing the right qualifications for admissions is an important decision, but even in the current landscape it doesn't have to be a particularly difficult one," says Ms Johnson. "Applicants need a fair opportunity to prove their skills, and universities need valid results they can rely on."

There are some basic considerations that could be applied to evaluating any admissions exams for English proficiency. For example, is the integrity of the test and test centre protected via industry-standard security protocols? And is the test backed by clear and robust research and validation supports, including pretesting or trials of test materials?

Beyond that is the question of whether or not a test is fit-for-purpose for higher education, especially in terms of how well it measures the student's readiness to pursue advanced studies in English. Ms Johnson sets out some key questions in this respect: "Does the test meet the relevant stress tests for demanding academic study? Is there a focus on reading, writing, speaking, listening – and is there a focus on communicative language skills? So, in other words, a test that focuses specifically on real-life communication skills needed for success in higher education. If the student can really communicate, they are more likely to stay the course, to benefit academically, and to benefit from better employment prospects."

The other side of that coin is that with those important building blocks in place, tests that can demonstrate that relevance, reliability, and quality can open the door to a wider field of international candidates.

The real question, concludes Ms Johnson is, "Will this test increase my institution's reach and reputation? Is the test globally recognised by top employers and institutions? Is the test accessible to students of all backgrounds, for example arrangements for candidates with access issues or requirements?"

For additional background on those and other important considerations in selecting English proficiency tests for admissions, please download "Navigating the English language testing landscape", a free checklist and background brief from Cambridge Assessment English.