Survey finds majority of students struggling with mental health during COVID

- More than half of students responding to a global survey say that COVID has left them struggling with mental health

- Reports of mental health issues differ substantially between countries, with important implications for international educators

- International students face unique challenges as a result of the pandemic and may also be more hesitant about asking for help when suffering from a mental health crisis

- Strengthening mental wellness supports for international students will be incredibly important this year and next

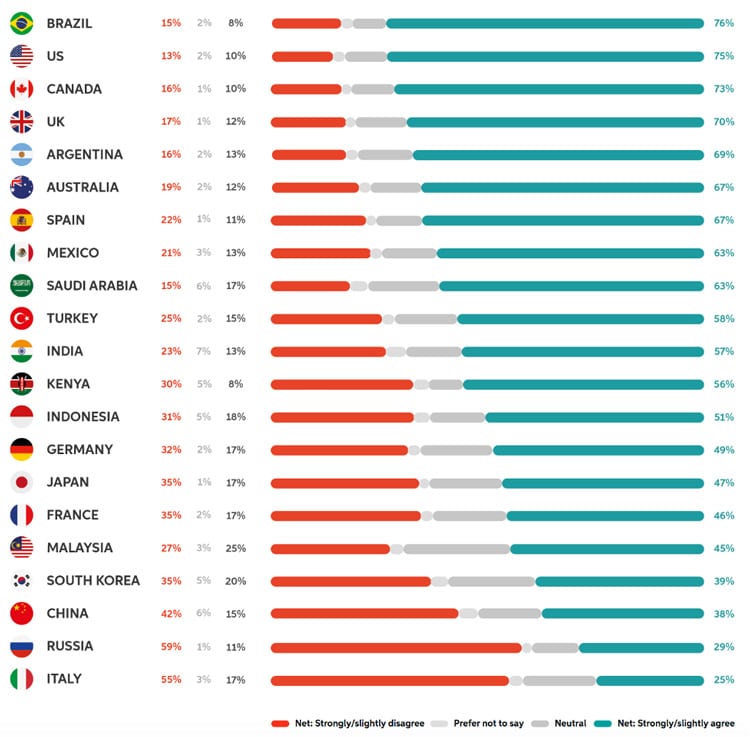

More than half (56%) of undergraduate students responding to a 21-country survey say that their mental health has suffered as a result of COVID. The survey, undertaken by Chegg, gathered responses from 16,839 students aged 18–21 in October and November of 2020.

Proportions of students saying their mental health had deteriorated rose in Western countries, with at least 70% of American, Canadian, and British students saying they had suffered in this way. More than three-quarters (76%) of Brazilian students also said they were having mental health issues related to COVID. Reports of mental health issues fell substantially in Italy (25%) and were low as well in Russia (29%), China (38%), and South Korea (39%).

The diverging self-reports of mental health or lack thereof across the survey sample suggest that there is a cultural dimension to how students assess their mental health and whether they feel able to reach out for help if they are experiencing anxiety, depression, or other mental health challenges. This is of special importance for international educators in terms of the quality and quantity of mental health counselling they provide for students – particularly since other research confirms that many international students are less likely to both be aware of and access mental health supports than domestic students are.

China, for example

Speaking as a panelist at a session devoted to international students’ mental health at the NAFSA conference in 2019, Justin Chen, the co-founder of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Cross-Cultural Student Emotional Wellness and an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard University, explained that Chinese students in particular can have trouble seeking treatment for mental health struggles, in part because they may have the added burden of coming from a culture in which depression and anxiety have traditionally been stigmatised.

More broadly, Mr Chen noted that Asian students can feel pressure to conform to the stereotype of the high-performing academic student studying in the West.

Mr Chen, along with several other professionals, spoke on topics including:

- What behaviours and signs professors and counsellors should look out for that might suggest that an international student is having trouble, including “deterioration in personal hygiene or dress, dramatic weight loss or gain, noticeable changes in mood, excessive absences, academic problems, social isolation, unusual behaviors, drug and alcohol abuse, or threat of harm to themselves or others.”

- The need for counselling to consider the language preferences of students;

- The importance of reassuring students that accessing support is a strong rather than weak action, and that doing so will be confidential and will not go onto their academic record or affect their visa status;

- The idea of having counsellors present in orientation week so international students know that they have this support available to them if they need it.

COVID has heightened a sense of isolation

Another survey conducted in 2020 by researchers at the University of Hong Kong assessed international students’ mental health in the pandemic and it interestingly segmented student respondents into those who stayed in the host country when COVID hit and those who returned home. The research found that 84% of all students in the sample faced “moderate-to-high” levels of stress but that students who remained in the host country “ … had significantly higher stress from COVID-19-related stressors such as personal health and lack of social support, higher perceived stress, and more severe insomnia symptoms.”

The quickly changing, sometimes contradictory, often alarming messages that all students were subject to during the first months of COVID would have been particularly distressing for international students far from home, away from their families. These students might have had language barriers and many would have also been navigating complicated questions about whether to stay or leave and what either decision would do to their chances of completing their programmes. In the US, some even faced the prospect for a few weeks that they would be forced to return home if their programmes transitioned online. These complications would have been on top of the acute universal worry that everyone had about contracting COVID and the paper’s researchers urged “educators and mental health professionals to provide appropriate support for international students, particularly the stayers, during the pandemic.”

Student support is key

As much hope as the vaccines provide, the pandemic is not over and many thousands of international students are still facing challenges that domestic students do not face, from financial issues (e.g., not being able to work enough and/or not being able to receive the same emergency funds as other students) to logistical challenges (e.g., continuing border closures in some countries).

These students will need more support than ever this year and next. Strengthening mental health services infrastructure for international students will therefore be key for student retention and success and also an important aspect of recruitment as we move to and through the latter stages of the pandemic.

For additional background, please see: