Rapid growth in Indian higher education system, but report calls for sweeping reforms

India’s higher education system is one of the largest in the world, with close to 52,000 institutions, and enrolment in it is now four times what it was in 2001, according to a November 2019 Brookings India report entitled Reviving Higher Education in India. There are now 35.7 million students enrolled in programmes at the country’s universities and colleges.

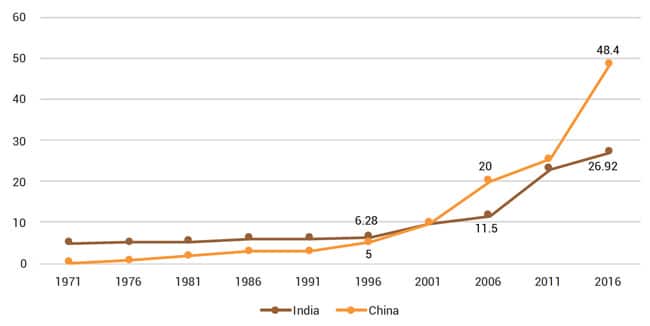

The gross enrolment ratio (GER) in India was 26.3% as of 2016. While this represents more than double the GER of a decade earlier (which was 11.5% in 2006), it remains below the target of 32.2% for 2022 set by the Ministry of Human Resource Development. Demand for study abroad is incredibly strong. Just over 750,000 Indians went abroad to study in 2018, making India the world’s second-largest source country after China for international students and one of the world’s fastest-growing outbound markets.

Why, with tens of thousands of institutions available in their own country, are so many Indians choosing to study overseas? The Brookings India report points to “low employability of graduates, poor quality of teaching, weak governance, insufficient funding, and complex regulatory norms,” as issues facing the sector. In addition, the report notes, the much-expanded higher education sector is still no match for demand, especially at the postgraduate level, and access to quality higher education is a persistent issue.

If the country is to achieve its goal of truly “massifying” higher education – i.e., enabling a critical proportion of its citizens to access quality higher education in the country – serious reforms are needed, says the report. A higher education system is considered to be massified, or “universal,” when the GER is above 50%.

What has China done differently?

The report contrasts trends in India and China. The latter country has also seen a massive expansion in its higher education system, but China has accomplished it differently and with a greater overall impact on educational and economic development.

China’s gross enrolment rate has climbed far more rapidly than India’s since 2001, as the following chart (based on UNESCO data) indicates.

Why the marked difference in GER growth over this time period?

The Chinese government vastly increased its investment in its higher education system, while India went about its expansion by (1) reducing its funding and (2) inviting private investors in a bid to expand capacity. This, in turn, has resulted in a fragmented Indian system with thousands of often poorly regulated providers and relatively few students per institution.

The report notes that,

“Indian HEIs, on average, have about 690 students. Chinese HEIs, on the other hand, have 16,000 students per HEI. Experiences from China and developed countries suggest that bigger HEIs with a high student count are easier to manage.”

More clustering of smaller Indian higher education institutions is a recommendation put forth in the report.

Few opportunities for postgraduates

The huge numbers of Indian students studying postgraduate degrees at foreign universities are in large part driven by one fact: there’s very little for them to pursue at this level in India. As of 2018/19, only 35% of Indian higher education institutions are offering postgraduate programmes and just 2.5% are offering PhD programmes. Many of these programmes are at privately managed institutions within a context of poor regulation and/or accreditation.

The report strongly urges the government to invest more in expanding India’s postgraduate capacity, explaining that private institutions find it “commercially unfeasible” to run such programmes.

Lack of innovation

More than 50% of students in India’s higher education system are studying in one of three programmes: Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Science (BSc), and Bachelor of Commerce. These programmes are three years in duration, and the report notes that because of how syllabuses are prescribed, there is “limited scope for innovation” and also that only elite colleges offer serious linkages with industry. Without industry connections, the route from graduation to employment can easily fail.

Brookings recommends limiting the number of these programmes and refining existing programmes to include more vocational skills to better prepare students for the job market. The issue is critical: the report notes that many graduates of three-year programmes – and these are 50% of all graduates in the Indian higher education system – are failing to find places in the formal economy, falling instead into occupations outside of it and temporary employment.

Challenges abound

Other problems in the higher education system, says the report, are:

- “High entry barriers, poor incentive structures, stringent tenure rules and rigid promotion practices [leading] to a limited supply of faculty;

- Less than 10% of enrolled students having access to financial aid, and millions more simply unable to afford higher education at all;

- Faculty shortage, low inputs available for research and inadequate industry linkages [relative to those in the US, China, and South Korea] limiting India’s ability to produce a ‘skilled, productive and flexible labour force;’

- Not enough financial, administrative, and academic autonomy given to institutions;

- Reduced government funding for central universities; those who can afford it go to a private institution where tuition fees are almost twice that as those at a public institution;

- Limited assessment and accreditation capacity;

- Complicated distribution of roles and responsibilities across the multiple agencies and providers, hampering innovation and creativity.

Crucial to any chance of India creating a high-quality, accessible education system with compelling opportunities at both the undergraduate and graduate levels is a system that produces well-qualified teachers and faculty: “Adequate compensation, in terms of monetary consideration as well as career security (tenure-track), should be provided to teaching staff to incentivise them.”

For additional background, please visit: