China’s rapid urbanisation becoming a global story

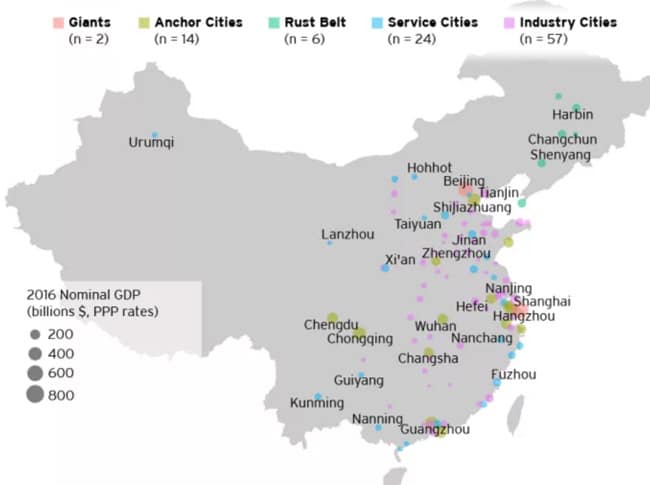

The economist and Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz has been widely quoted as predicting that urbanisation in China is one of two transformative forces that will most impact global prosperity in the 21st century (the other: technological innovation in the US). However you may feel about economists, the movement of greater numbers of Chinese to a growing number of large Chinese cities is an unmistakable trend, and notable in part for its sheer scale. Forecasters expect that roughly 70% of the country's population – or about a billion people – will be living in cities by 2030. And a new report from The Brookings Institution only underscores the importance of the continuing migration toward large cities throughout the country. Brookings actively tracks the performance of the world's 300 largest metropolitan economies, as measured by GDP and employment data. In 2014, less than 50 of the top 300 cities were found in China. In an updated tracking study released earlier this month, China was home to just over a third (103) of the total. The pace of this change is being driven by the still-hot economic performance of many of China's cities, which as a group continue to outpace the growth of large cities elsewhere in the world. In a recognition of the complexity and variety of cities within China, Brookings has classified this field of more than 100 large urban centres into five "city types" based on size, composition of the local economy, and growth patterns. They include:

- "Giants": A category that belongs only to the two mega-cities of Beijing and Shanghai.

- "Anchor Cities": A next tier of 14 large cities that together account for about a quarter of China's GDP: Tianjin, Chongqing, Zhengzhou, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Guangzhou, Wuhan, Changsha, Chengdu, Qingdao, Suzhou, Wuxi, Ningbo, and Shenzhen.

- "Rust Belt": Six cities previously noted for their prominent role in China's declining steel and coal industries: Harbin, Daqing, Changchun, Jilin, Shenyang, and Dalian.

- "Service Cities": Another 24 centres where the local economies are heavily weighted toward the service sector.

- "Industry Cities": A final cohort of 57 metropolitan areas where industry (e.g., manufacturing or extractive industries) continues to drive the local economy.

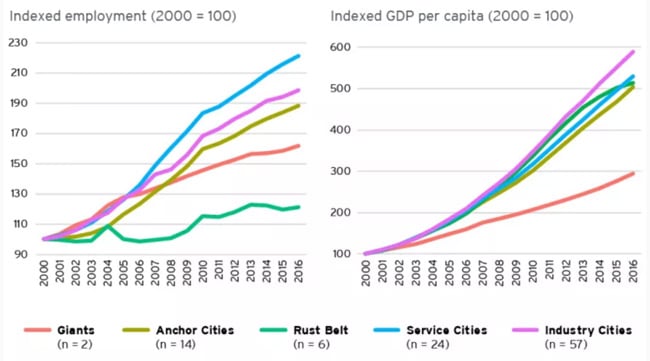

The report notes as well that each category of city demonstrates different employment and growth patterns. "While Beijing and Shanghai still get most of the headlines, they no longer serve as the main engines of national economic growth," says Brookings. "Domestic migration has been shifting from Beijing and Shanghai to smaller cities for a decade...The gap in average living standards (measured by GDP per capita) between the two Giants and other Chinese metro areas is also shrinking. Since 2000, GDP per capita in China’s 101 metro areas outside of Beijing and Shanghai rose twice as fast as in the two Giants."

This relationship between Beijing and Shanghai and the other categories of urban centres in China is illustrated in the charts below. They reflect that growth in employment, and also in economic output, in Beijing in Shanghai has been eclipsed by that of other Chinese cities.

Most Recent

-

US: Student visa issuances fell by -36% in summer 2025; OPT uncertainty among factors affecting international student demand Read More

-

Canada and India deepen educational ties; India repositions as an equal player in international education Read More

-

Inbound, outbound, and transnational: the landscape for international education in China continues to evolve Read More