Global survey highlights regional trends for English proficiency

The 7th annual EF English Proficiency Index (EPI) was released earlier this month. As in previous years, the EPI ranks the proficiency of non-native-speaking countries around the world – the field has expanded to 80 this year – based on a global sample of EF Standard English Test (SET) test takers.

This year, the sample is larger than ever with the rankings based on more than a million completed language tests. Also new for 2017, the index features several additional African countries for the first time: Angola, Cameroon, Nigeria, and South Africa.

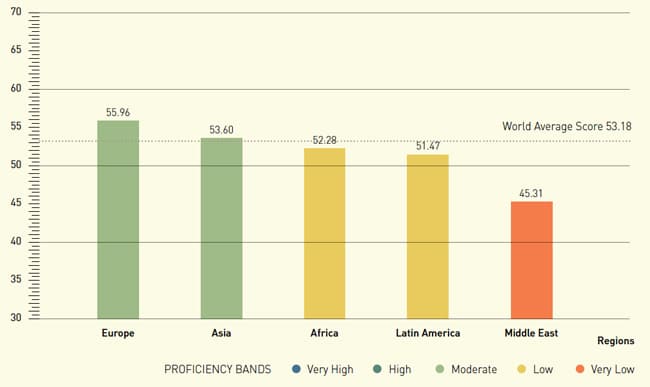

The following chart describes the broad picture of English proficiency at a regional level. Europe remains at the top of the regional table again this year, with Asia close behind, Africa and Latin America in the middle of the pack, and the Middle East lagging well below global averages.

The big picture

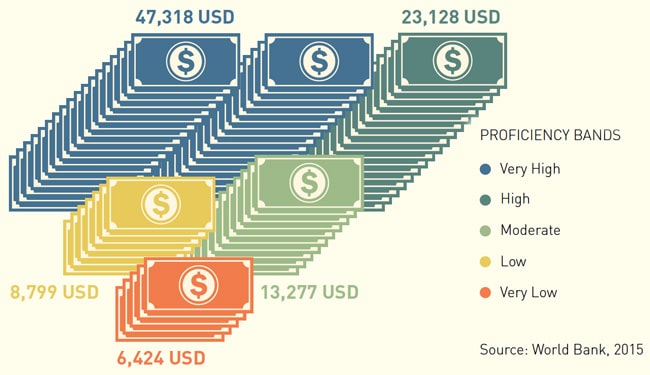

In this regard, the 2017 EPI makes some interesting observations about the different approaches that countries around the world are taking to build English proficiency. As in earlier editions of the index, EF finds strong correlations between English proficiency and income levels and economic growth, adoption of technology, research and innovation, and other important social indicators. And it is these findings that essentially underpin the massive investments in and policies for promoting English proficiency among their citizens.

- English as a medium of instruction in schools. Certainly, English may be more widely used in private schools but this year’s EPI report notes that a number of countries are experimenting more widely with English-taught programmes, notably Morocco which has begun to offer English-enhanced high school courses.

- Curricular reform, particularly with respect to aligning English assessments in the country with international standards.

- Internationalisation of higher education, including the introduction of expanded English-taught programmes at local institutions. “Japan and Russia have national programmes underway to increase the use of English in universities,” notes the report. “And many individual universities in other countries, such as South Africa, are making similar adjustments.”

- Scholarships for study abroad. While the recent examples of massive scholarship programmes in Saudi Arabia and Brazil tend to dominate our imaginations in the respect, there are a number of other notable scholarship supports in markets such as Hungary and Mexico.

- Adult education, while used more sparingly, some countries, notably Singapore and Hong Kong, have invested in new programmes to boost the English skills of adult learners.

- Learning technologies are always a fluid area of both education policy and actual usage in schools, but there are interesting examples that tie back to English proficiency. These include Uruguay, which is using online tools to connect teachers in English-speaking countries to its primary school classrooms, and Nigeria, where SMS is being used to provide ready access to English training.

- Last but not least: training the trainers. EF notes a number of local initiatives in this category, including an upskilling programme for language teachers in Malaysia and a grassroots initiative in Angola.

“Every year, countries spend billions to improve their citizens' English proficiency,” concludes the EPI report. “Mastering a foreign language takes years, if not decades, and there is no one-size-fits-all approach.” “The global adoption of English is not a testament to the cultural supremacy of any one country, but rather a reflection of the need for a shared language in our deeply interconnected world.” For additional background, please see:

- “Annual ranking says Europe still leads on English proficiency”

- “Anytime, anywhere: How online and mobile technologies are transforming language learning”

- “Latest language travel data points to slowing growth in 2015”

- “English skills a key for mobility and employment in the Middle East and North Africa”