OECD charts a slowing of international mobility growth

Every year, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) produces a massive report that rolls up a considerable range of education data and trends. The latest installment in this series, Education at a Glance 2017, was released last week and it describes a rapidly expanding tertiary population worldwide, along with continuing growth in education spending throughout the OECD area.

Across OECD states, the percentage of 25-to-34-year-olds with a tertiary qualification has increased considerably over the past decade, from 26% in the year 2000 to 43% in 2016. And those students, the OECD conclusively finds, are more likely to be employed and with much better earning prospects (56% better, on average) when compared to peers without a tertiary education.

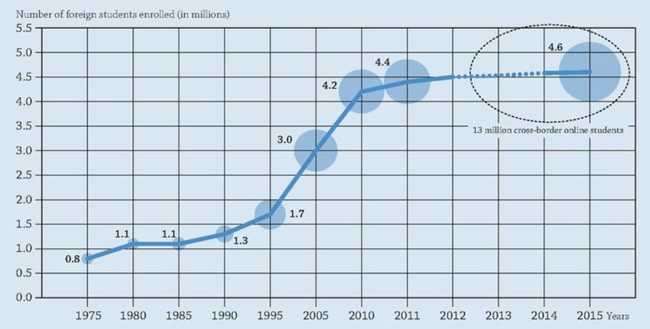

On the international front, Education at a Glance 2017 highlights the dramatic growth in global student mobility, particularly during the 20 years from 1990 to 2010. As the following chart illustrates, the total number of tertiary students enrolled outside of their home countries had hovered around one million from the mid-1970s until the late-1980s. The number of higher education students abroad began to climb rapidly at that point, and is estimated at nearly five million today.

The OECD has elsewhere projected that the total number of internationally mobile students will reach eight million by 2025. But Education at a Glance 2017 puts that forecasts in an interesting light with an examination of the some of the factors that are acting on broad patterns of mobility in the world today.

These are especially meaningful when we consider the latter years in the chart below, where growth in outbound mobility has begun to flatten out noticeably from about 2010 on.

Push and pull

“The increase in foreign enrolment has been driven by a variety of domestic and external, push (encouraging outward mobility) and pull (encouraging inward mobility) factors,” says the OECD. “The skills’ needs of increasingly knowledge-based and innovation-driven economies have spurred demand for tertiary education worldwide, while local education capacities have not always evolved fast enough to meet a growing domestic demand. Rising wealth in emerging economies has further prompted the children in a growing middle class to look for educational opportunities abroad. At the same time, factors such as economic (e.g., costs of international flights), technological (e.g., the spread of the Internet and social media to maintain contacts across borders) and cultural (e.g., use of English as a common working and teaching language) have contributed to making international mobility substantially more affordable and less irreversible than in the past.” At the same time, the OECD report highlights a number of important trends that are acting on the scale and shape of international mobility today, including an expansion of transnational education provision, the rapid adoption of online teaching and learning, and the emergence of major regional study destinations in Europe and Asia. “The global marketplace for tertiary education is likely to expand further as global demographic trends and a rising global middle-class spur demand and spending on educational products and services. Information and communication technologies (ICT) are also instrumental to this expansion,” concludes the report. “ICT not only reduce migration costs, but also increase the reach of domestic education. There are already an estimated 13 million cross-border online students, though the impact on the scope and patterns of international student mobility remains unclear.” Other factors that will bear on the longer-term growth trend toward that projection of eight million internationally mobile students by 2025 include:

- Immigration policy in major host countries, particularly with respect to any restrictions on student mobility as well as work opportunities during and after study.

- Macro economic trends, and especially those that bear on exchange rates between the currencies of major sending and destination countries.

- Tuition policy for foreign students, which, as the report points out, currently varies considerably with the OECD with some study destinations charging significant differentials for visiting students.

- Education standards and quality assurance: “Increasing compatibility and comparability across national education systems is a prerequisite for international student mobility. Educational accreditation standards and information play an important role in removing barriers to student exchanges and supporting the global market for advanced skills.”

- Language of instruction: English remains the lingua franca of an increasingly globalised world, and major English-speaking destinations, including the US, the UK, Australia, and Canada, host a majority of mobile students. However, there are two forces acting on this historical market dominance. First, the rapid expansion of English-taught degree programmes at both the undergraduate and post-graduate levels, and especially in Europe. Second, the emergence of major regional study destinations whose native languages also figure prominently in the global economy, including Germany, Russia, and China.

Needless to say, each of these factors will bear on the competitive landscape for international student recruitment going forward. And the stakes are high for host countries and institutions alike, both in terms of immediate education export revenues but also with respect to long-term socio-economic impacts. “In the short-run, international students often provide tuition fees…they also contribute through their living expenses to the local economy,” says the OECD. “Attracting mobile students, especially if they stay permanently, is [also] a way to tap into a global pool of talent, compensate weaker educational capacity at lower educational levels, support the development of innovation and production systems and mitigate the impact of an ageing population on future skills supply in many countries.” For additional background, please see: