UK: Projecting Brexit fallout as non-EU enrolment stays flat

Earlier today, British Prime Minister Theresa May stepped to the podium at Lancaster House in London and set out 12 guiding principles for the UK’s departure from the European Union. Prime Minister May has said that she will formally trigger the exit negotiations by the end of March. In the meantime, today’s speech offered some clarity as to how the UK will approach the process. Of particular note for international educators was that immigration remains front and centre within the government’s exit strategy. "We will continue to attract the brightest and the best to work or study in Britain - indeed openness to international talent must remain one of this country’s most distinctive assets," said Ms May. "But that process must be managed properly so that our immigration system serves the national interest.” The debate continues in Britain as to whether foreign students should be included in the country’s net migration targets. Immigration is a major political issue in the UK, however, and the government continues to give every indication students will not be excluded from the net migration figures. In recent months, the government’s position on this question has in turn given room to considerable speculation about further visa controls. In an October 2016 conference speech, Home Secretary Amber Rudd indicated that new visa rules were in the works. The Home Secretary also set out a case at the time for a two-tiered visa system, where visa policy would be linked to the quality of the programme or institution. More recently, The Guardian has reported that the Home Office is considering dramatic reductions in the number of visas available to foreign students.

Modelling the future

These recent reports provide the backdrop for a new analysis released last week by the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI). Reflecting a variety of assumptions and projections with respect to relative currency values, tuition rates for EU students, and student immigration levels, the HEPI concludes that any new restrictions on foreign student mobility could cost the British economy up to £2 billion per year (US$2.5 billion). The key aspect in this projection is that it anticipates further restrictions on inbound mobility. Absent those, the authors believe the UK has the chance for significant gains in international education. "In a period of significant economic uncertainty, there are substantial export opportunities available to UK higher education institutions," said report authors Gavan Conlon and Maike Halterbeck. "However, these opportunities can only be seized if universities are allowed to deliver them…With an economic value of £2 billion per annum, there is ample reason to allow more international students to come and study in the UK, thereby boosting UK prosperity, as well as maintaining the UK’s global reach and influence." HEPI Director Nick Hillman added, "Were the Home Office to conduct yet another crackdown on international students, then the UK could lose out on £2 billion a year just when we need to show we are open for business like never before. Removing international students from the net migration target would be an easy, costless, and swift way to signal a change in direction."

No growth in non-EU numbers

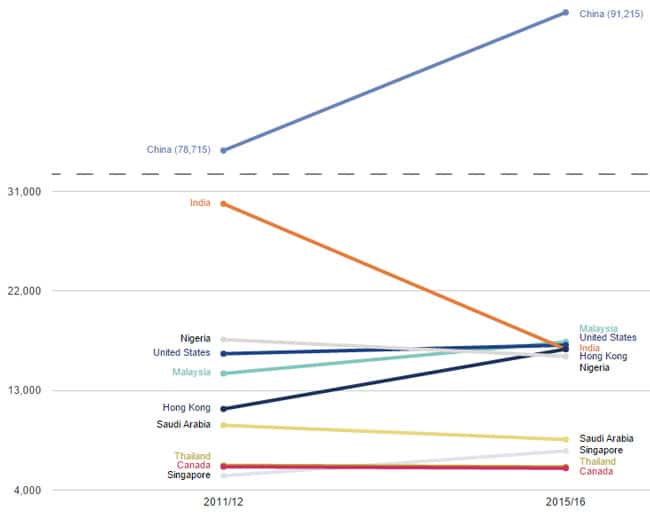

For the moment, foreign enrolment in the UK remains essentially flat. The latest data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA), also released last week, shows that total higher education enrolment in Britain creaked up by 1% in 2015/16. Foreign students – whether from the EU or not – accounted for nearly 20% of that total.

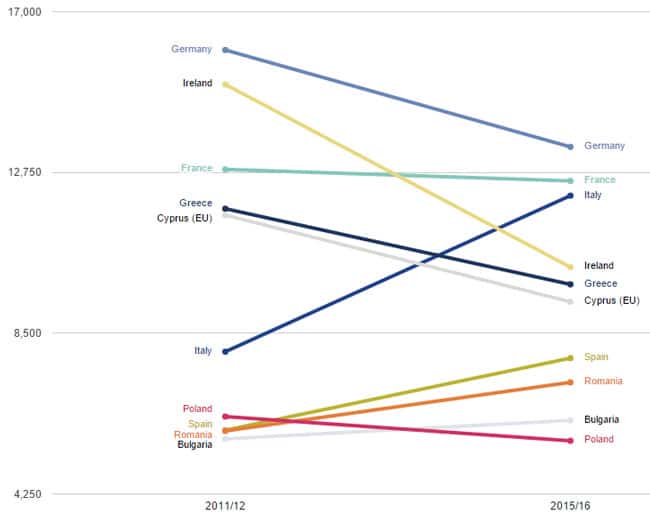

HESA finds, on the strength of notable declines in German and Irish enrolments in particular, that EU enrolment across the UK fell by 4% between 2011/12 and 2015/16. As we also reported recently, this pattern may well extend into 2016/17 and 2017/18 as the number of EU students applying in early UK admissions cycles this year has fallen off by nearly 10%.

Most Recent

-

British Council says student recruitment to UK higher education will get a boost this year from South Asia and the “Trump effect” Read More

-

New Zealand expands post-study work opportunities for international students Read More

-

As Iran retaliates across the Middle East, schools close, students worry, and institutions reassess transnational education Read More