French government calls for new strategy for transnational education

France is lagging behind in transnational education and needs a new national strategy to expand its market share of higher education programming abroad. This is the central conclusion of a new report from France Stratégie – formally the General Commission for Strategy and Foresight (CSPF) – a central planning agency attached to the Office of the Prime Minister.

The report, L’enseignement supérieur français par-delà les frontières: L’urgence d’une stratégie (“French Higher Education Across Borders: The Urgent Need for a Strategy”), was published on 26 September and presented the same day to Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Development Jean-Marc Ayrault and Minister of State for Higher Education and Research Thierry Mandon.

It finds that French institutions currently deliver just over 600 programmes abroad, and operate 40 branch campuses worldwide. Those programmes enroll an estimated 37,000 students, including nearly 6,000 in distance learning.

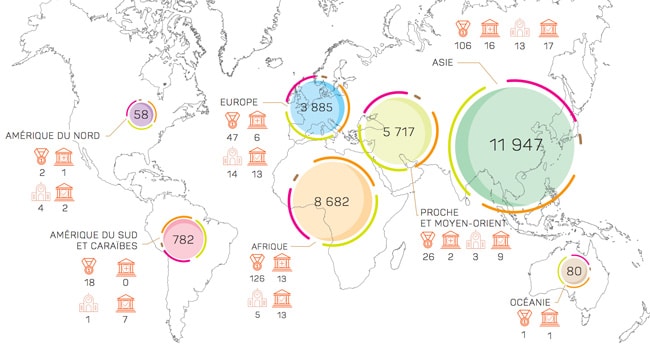

Roughly 40% of France’s transnational education (TNE) enrolment is in Asia, another 30% in Africa, and 20% in the Middle East. And nearly half of the students enrolled in French TNE programmes are found in five countries: China, Lebanon, Morocco, Vietnam, and India. Indeed, much of France’s current TNE activity is concentrated in countries and regions where it has a former colonial interest or other strong historical ties.

- Supporting capacity building for internationalisation teams within French institutions, and improving data systems for tracking and reporting on TNE programmes

- Strengthening quality assurance mechanisms for French programming abroad

- Expanding funding supports for TNE programming and providing greater flexibility for institutions in the pricing and financing of programmes abroad

However, a related commentary in University World News from François Therin, the director of the Ecole de Management Leonard de Vinci in Paris, adds some practical considerations from the perspective of French institutions. “Many French higher education institutions are now following the path taken by UK or Australian universities but without the same resources,” he notes. “UK and Australian institutions mainly went abroad to source students (incoming or in-country) because they lacked financial resources. They were hungry. French institutions, comfortably established in their national market, did not feel the need for extra resources…It is only very recently, now that the national market has become more difficult and more competitive and now that public money is scarcer than ever, that [French institutions] realise that international expansion (in countries, online, etc) is the main way to increase their budgets.” Mr Therin adds that most institutions nevertheless lack the resources needed to invest in market development abroad, and this is perhaps where one of the areas of state action identified in the France Stratégie report – reform of funding models and greater flexibility in pricing and financial arrangements – may especially come to bear. For additional background on internationalisation in France, please see “France aims to counter slowing international enrolment growth”.